This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Alexis Madrigal: Welcome to Forum. I’m Alexis Madrigal. These men—these powerful men—who do the wrong thing when they could do the right thing. Isn’t that so much of what our world is reckoning with right now? From the White House to the Epstein files to the fossil fuel industry, it’s all these men who cause harm in pursuit of power and money, all the way until they die in their sleep.

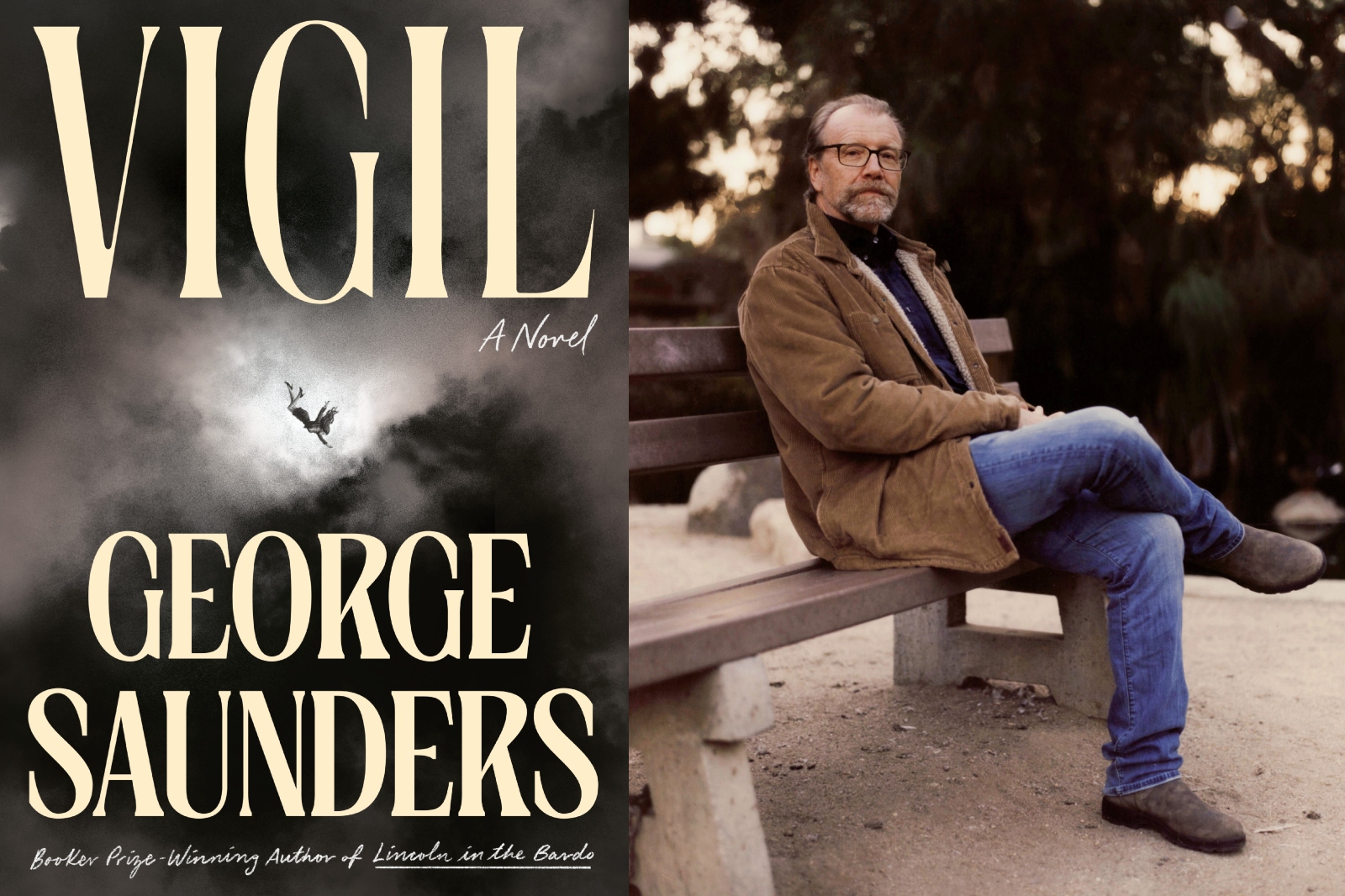

George Saunders’ latest novel, Vigil, introduces us to one of these men: KJ Boone, an oil man who has, we learn, single-handedly done more to cause and hide the reality of climate change than anyone else on Earth. What, then, does he deserve in death—if not in life, which has gone quite well for him?

Here to discuss is George Saunders himself. Welcome back, George.

George Saunders: Hey. It’s always nice to be here. Thank you.

Alexis Madrigal: So nice to see you. Is this a book about climate change, or a book about death?

George Saunders: Yeah. It’s not about climate change, because that’s a buzzkill. You know, the way I approach this, I don’t really know when I start. So I put climate change in it and death in it, thinking, you know, something will come out of it. And then you always hope it’s about some other thing.

It’s got those things in the foreground, but the heart of the book—you’re going to discover as you go. So that’s the fun of it. If you knew in advance, you’d just be kind of preaching. It’s fun to say, well, if I put those two things in there, at least it won’t be nothing, and then we’ll find out what it actually is.

Alexis Madrigal: There’s a third element in the book, too, and that’s Jill “Doll” Blaine. She’s sort of this angel-ish character. How did you think of her? She says “one of our ilk” a lot in the book.

George Saunders: She’s kind of—I mean, she’s the ghost, basically. But “ghost” is a little reductive. I think of her as an eternal being. She died in 1976. I thought of her as one of the girls in my neighborhood, or slightly older ladies, you know.

Basically, her thing turned out to be that she had a pretty loving heart, a pretty good marriage, and then it just ended too soon. I thought of all that released—or pent-up—energy of somebody who’s looking forward to a full life and suddenly, no. You know?

So that was her, and I really kind of fell in love with her. She’s a sweetheart, but she’s conflicted. She’s eternal and, as she says, elevated—very generous, very loving toward all these people she’s kind of death-dueling with. But we also find out she’s not quite over being alive. She smells a steak and she goes nuts.

Alexis Madrigal: Why don’t you read a little passage about her?

George Saunders: Yeah. So she says:

I knew very, very well where I was: underground, Stanley, Indiana, Sacred Heart of Mary Cemetery, beneath a willow, fifteen feet from a stone bench upon which a Slurpee cup rested and had been resting now for the better part of a year. And what? A desiccated brownish-green figure of medium height, length cleaved in half at approximately the hip line, left arm disconnected at the shoulder, a fuzz beard of mold on what was left of his cheekbones, wearing still the outfit Lloyd had picked out for me—beige skirt, pale pink blouse, black pumps, my favorite in life, a fact Lloyd had sweetly remembered even in his grief.

All of it marked by a disappointingly economical stone reading: J. Blaine, wife, 1954–1976, the best Lloyd, an assistant deputy, could afford.

But joy, joy: that hideous, hideous figure was not me—not anymore—nor was I the woman that figure had been when vital, i.e., before her demise, odiously burdened with her stunted diction, her limited view, her nominal ability to comprehend, her constrained love, which she could direct only toward those precious few with whom she had been randomly placed into proximity—i.e., friends, family, husband.

No. This now was me: vast, unlimited in the range and delicacy of my voice, unrestrained in love, rapid in apprehension, skillful in motion, capable equally of traversing, within a few seconds’ time, a mile or ten thousand miles. The champion of a cause I would never forsake—to comfort, to comfort whoever I could in whatever way I might. For this was the work our great God in heaven had given me.

Alexis Madrigal: That was George Saunders reading from his new novel, Vigil. It struck me—it’s kind of like a superhero. She’s a superhero of comforting, she thinks.

George Saunders: Yeah.

Alexis Madrigal: And I was also thinking as you were reading it: we’re kind of both of these things at some level, right? We’re this decaying body from almost the beginning, and then we have this possibility, at least, of being—

George Saunders: I don’t know—something more. Yeah. We all have that intuition that for all the stress of life and the push and shove, we’re our best selves when we step out of that a little bit and reach across and comfort.

The trick with her, though, is that she has a bit of what I’ve heard Buddhists call “idiot compassion.” She thinks if she comes to your house and you’re dying, all she has to do is say, “It’s fine,” or, “Who could you have been but who you are?” And for certain people—this guy, KJ Boone, is one of them—that’s a little tepid.

A guy like that has to be brought to some kind of accounting, and it’s not really in her range to do it. That’s one of the tensions of the book.

Alexis Madrigal: Luckily, there’s a third character—the Frenchman who helped invent the internal combustion engine—

George Saunders: Sounds like such a calm, realistic book.

Alexis Madrigal: Just a zany comic novel about death and climate change. These other characters come along to aid her in her task, in a sense.

George Saunders: In a way. Again, I don’t really know what a book’s about when I start, but this one started asking me: how do you comfort somebody in their last hours—or anytime? What is comfort, really? When you feel love and empathy, what is the functional thing to do with it?

Certainly, you can do what she does, which is assuage and avoid. But there’s another school of thought, familiar to me from Buddhism, which is that you can be quite wrathful. What’s happening in our country right now—the incredible cruelty—you don’t stop that by putting your hands together and doing a gentle bow. You have to do it another way.

If you can do that right, you’re compassionate in every direction. You’re compassionate for the victims, especially, but you’re even protecting the perpetrators. As I was writing the book, the administration changed, and this question kept coming up: how do you comfort, how do you correct, without surrendering yourself? That’s the trick.

Alexis Madrigal: What do you ultimately want KJ Boone to do? To repent internally? He can’t talk anymore.

George Saunders: That’s all he’s got. He can’t talk, and there’s no way he can undo what he did. I thought about Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich. There’s a beautiful moment where this man, suffering from stomach cancer, realizes he hasn’t lived in alignment with the truth of his own life.

He finally says, “All right, maybe I didn’t do it right.” You feel a little relief come in. Then he thinks, if I didn’t do it right, there must be a right way—and that’s a step closer to salvation.

With KJ Boone, it’s similar. If you clench up to the very end, that’s one outcome. If, even at the last minute, there’s a flicker of repentance, that’s preferable. The outside world doesn’t change, but for the person—and maybe in some universal sense—it’s better.

Alexis Madrigal: The afterlife has been a constant fascination for you going back to your first book of stories. What does that in-between space—between life and whatever’s beyond—do for you as a fiction writer?

George Saunders: Honestly, it’s just a way to get a spark. My normal mind, doing realism, can be a little tame. If I put in a Virgin Mary theme park, or ghosts or dead people, suddenly you can’t be your tepid realist self.

It shifts the temporal register. We can be sitting here talking, and the ghost of an old miner drifts in. Ninety percent of it is just trying to get the prose to sit up and have some fun.

As a side benefit, imagining death—even someone else’s—reminds me that that moment is supercharged with meaning, but this moment is too. How are you doing right now?

Alexis Madrigal: It’s like every point in a basketball game still counts, even though we focus on the ones at the end. Second-quarter points matter.

George Saunders: Perfect. Yeah. Perfect.

Alexis Madrigal: We’ve been talking with George Saunders about his newest novel, Vigil. We want to hear from you. Have you been with someone in the hours before their death, and what did you think your role was—as Jill “Doll” Blaine is in the book?