This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

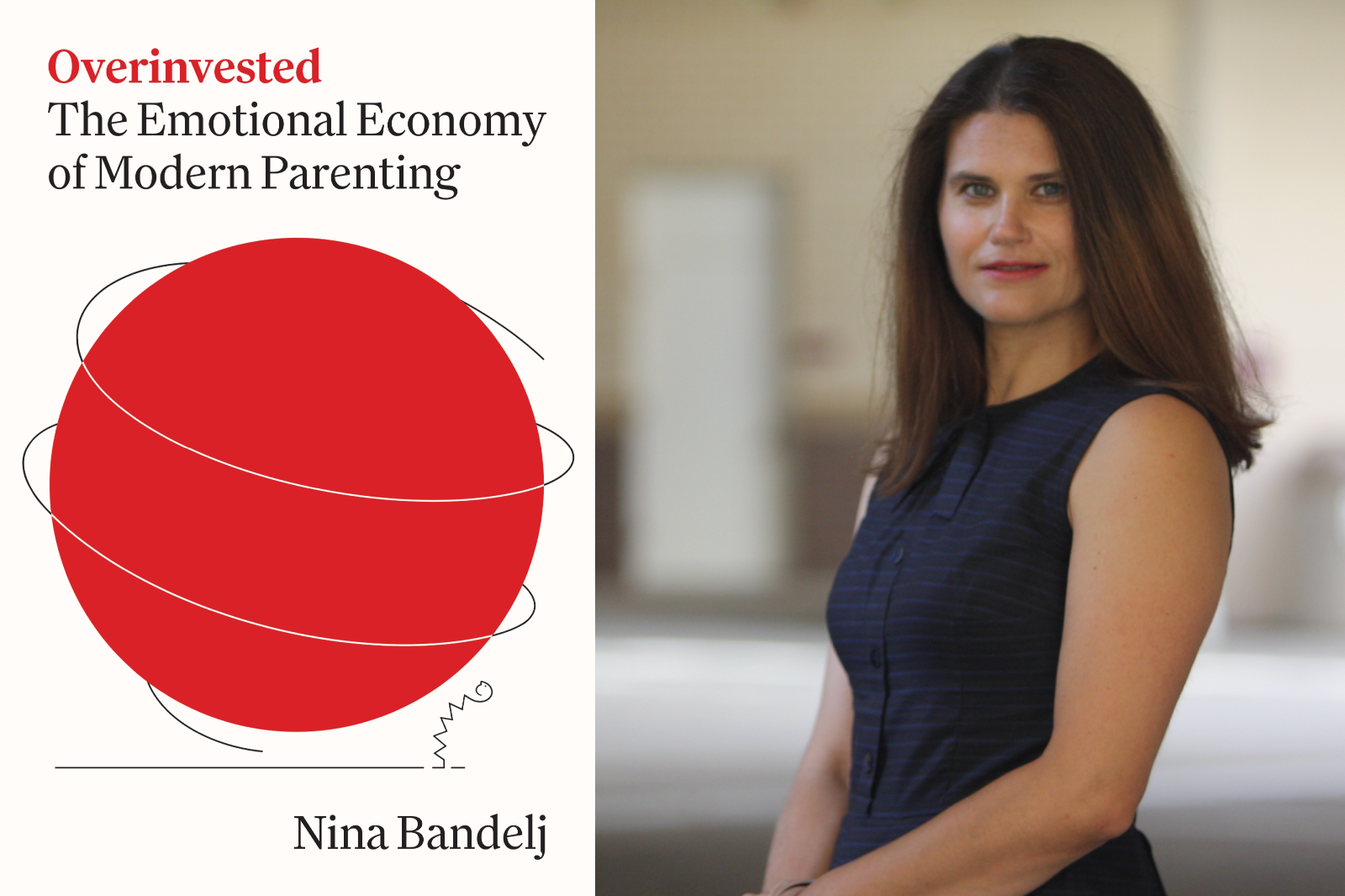

Alexis Madrigal: Welcome to Forum. I’m Alexis Madrigal. Our book this morning, Nina Bandelj’s Overinvested, is going to push some buttons. In it, the sociologist deconstructs one of the most powerful ideas in American society: that parents should give their all to their children emotionally and financially, and that doing so is the most important work anyone can do.

This is a relatively new development, she argues, shaped by the particular societal pressures of the last fifty years. I’ll quote her here: that we invest all in our children — our emotions, our money, even our souls — is not a natural response to either species survival or market competition. “Intensive parenting,” she writes, “is a product of a broader social transformation over the past several decades, one marked by a marriage between the economization of life and the emotionalization of life.”

In other words, as she writes elsewhere, nowadays Americans hold a deep conviction that, first, we should be devoted to work, and second, that the best kind of work is work you love. If so, parenting becomes the most sacred of all kinds of work. So this morning, we’re going to examine what most of us see as sacred work and try to understand how we came to see it that way — whether we want to or not. Welcome to Forum, Nina.

Nina Bandelj: Thank you so much for having me, Alexis. It’s a real honor to be in conversation with you.

Alexis Madrigal: We should also note that you’re a professor of sociology at UC Irvine, just for what it’s worth.

Nina Bandelj: I am.

Alexis Madrigal: So why don’t we start with the main argument of the book? Is it fair to summarize it in one sentence as: parents are doing too much?

Nina Bandelj: Well, I would say that, in some ways, parents are doing too much. But we also want to respect all the work that parents do. Let’s start with this fact: parents are exhausted. It’s so much work. It’s so much money. It’s our entire selves that we devote to our children. So to say it’s “too much” can be very hard to hear.

Alexis Madrigal: Yeah. I mean, why does it feel so natural to so many people that we would be doing it this way? As parents — I mean, I know you’re a mom. I’m a dad. And to me—

Nina Bandelj: Yeah, let’s say that out loud right away.

Alexis Madrigal: Yeah. When I hear these ideas, I think both, “Oh yeah, we’re doing too much,” and also, “But of course I am.”

Nina Bandelj: Exactly. How could it be otherwise? We want to devote ourselves to our children. We want the best for our children. Honestly, Alexis, these days it’s very hard to find something that people have in common. But when we talk to parents from very different backgrounds — across socioeconomic class, race, political persuasion, religious affiliation — they all share one thing: they want to do the best for their kids.

So I want to acknowledge that this is a good thing. We do share something meaningful. But I’d like us to think about how we can do this in a more sustainable way.

Alexis Madrigal: I mean, hasn’t it always been like this? It feels like there are plenty of examples throughout history of parents going above and beyond for their children. What do you see as different now compared to the long sweep of human history?

Nina Bandelj: That’s a great question. One could say parenting has always been hard. There’s this idea that it’s the hardest but most rewarding job — our parents did it, our grandparents did it. But there are important differences over time.

For example, Pew Research surveyed parents in a nationally representative sample in 2023 and asked how their parenting compares to how they remember their own parents parenting them. They didn’t say it was different in terms of discipline, values, or religion. What they emphasized instead was the emotional bond — the sacred bond you mentioned in your introduction. Parents today see that loving bond as primary, in a way they don’t think their own parents did.

That difference matters. If parenting is work — truly exhausting work — and most of us also have full-time jobs, that combination isn’t sustainable in the long run.

Alexis Madrigal: One thing I’ve been telling people about your book is this concept of the parental happiness gap. In surveys comparing parents and non-parents, the U.S. stands out among wealthy countries: parents here are significantly less happy than people without children. I always assumed that was just how the world works — but it turns out it’s really a feature of the United States.

Nina Bandelj: That’s right. It’s a feature of the United States and a few similar countries. But because it’s different elsewhere, it means it doesn’t have to be this way.

Research shows that public policies supporting parents — things like childcare, paid leave, social safety nets — reduce this parental happiness gap. And this helps us see that what feels like an individual struggle inside our homes is actually shaped by broader social conditions. As a sociologist, that’s something I pay close attention to.

Alexis Madrigal: Do you see this as a condition of American life more broadly? Or has parenting here become especially different because of this marriage of economization and emotionalization?

Nina Bandelj: I try to show that real change has happened. Today, about 40 percent of parents say that most days they’re so stressed they can’t function. That statistic comes from a report issued by the U.S. surgeon general in the summer of 2024, which declared parental mental health and well-being a public health crisis. That’s unprecedented.

We can also think historically about how we’ve understood children. A century ago, children contributed economically — on farms, in family businesses, through household labor. We’re not advocating for children working in factories, of course. But the social value of children has shifted. In the past, children labored for families; today, parents labor for children. Not just through paid work, but through constant, intensive parenting.

So I’m trying to understand how the social value of children has changed, and what that means for how we raise them.

Alexis Madrigal: We’re talking about modern parenting with sociologist Nina Bandelj, whose new book Overinvested argues that today’s parents may actually be hampering their children’s independence. We want to hear from you. Are parents doing too much? What’s the goal of your parenting?

Call us at 866-733-6786. That’s 866-733-6786. You can email forum@kqed.org or find us on social media — BlueSky, Instagram, Discord, and more.

One part of the book I found especially interesting touches on a familiar immigrant narrative: parents coming from elsewhere, sacrificing everything to give their children a better life. How is modern parenting different from that?

Nina Bandelj: I’m glad you brought that up. In sociology, we talk about the “immigrant bargain” — the idea that parents sacrifice by migrating, often explicitly for their children’s future. That aligns closely with today’s parenting ideals.

But we also know that immigrant children often contribute significantly to their families — translating, helping navigate institutions, supporting parents emotionally and economically. Children, even while growing up, are already becoming independent adults in many ways. They need opportunities to build skills and feel empowered.

While we didn’t interview children for this book, I suspect they would have a lot to say about wanting more independence — and about how parents’ well-intentioned efforts can sometimes backfire. That’s heartbreaking.

Alexis Madrigal: We’ll get into this more after the break, especially how the goals of parenting have shifted. One thing many listeners have probably noticed is that kids today do fewer chores and fewer part-time jobs than in the past. That ties directly into what you’re describing: parents seeing it as their responsibility to do everything for and around their children.

We’re talking about modern parenting with sociologist Nina Bandelj. Her new book is Overinvested: The Emotional Economy of Modern Parenting. We want to hear from you about how parenting is going — for you or for the people you observe. Call us at 866-733-6786 or email forum@kqed.org. We’ll be back after the break.