This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

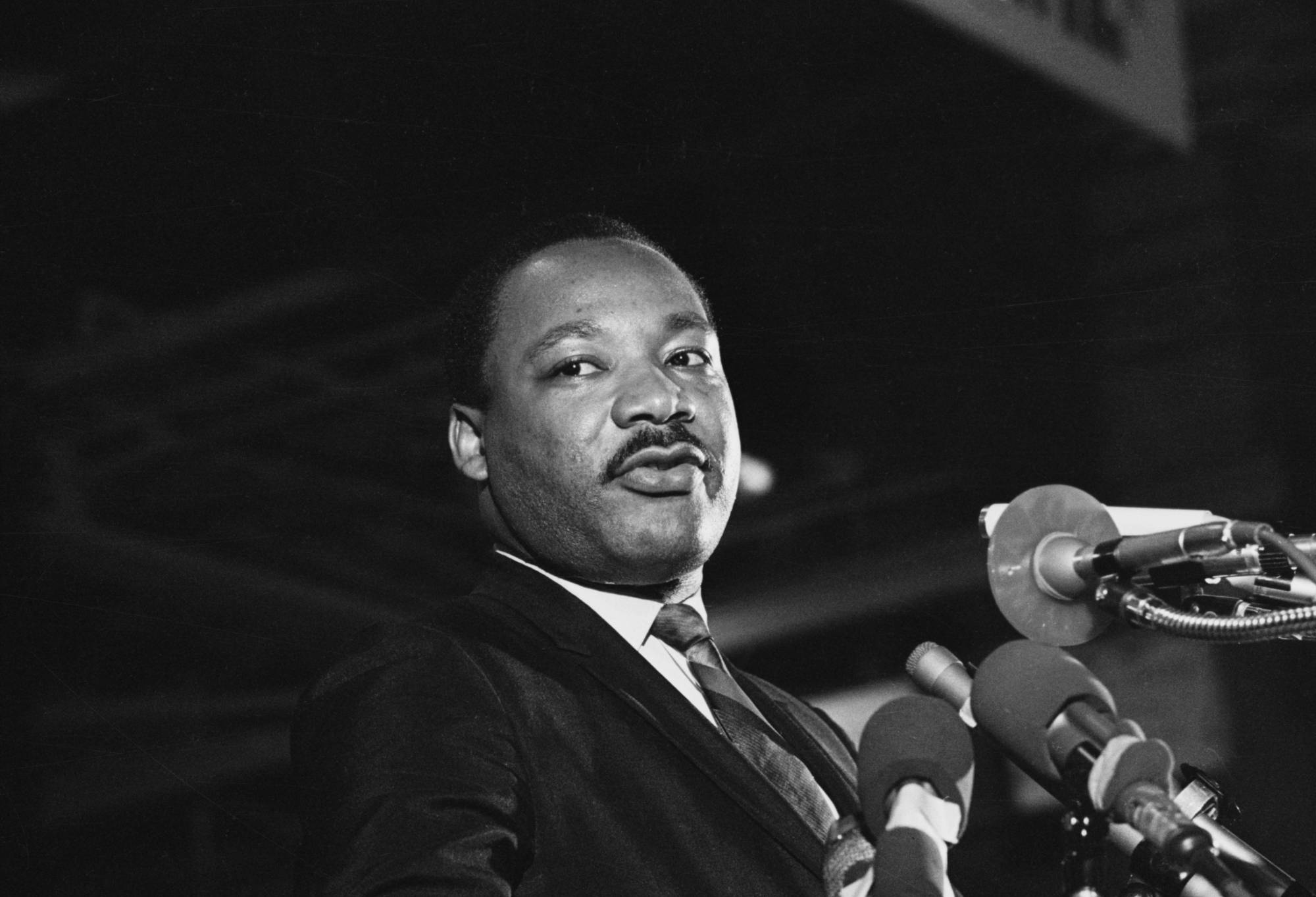

Alexis Madrigal: Welcome to Forum. I’m Alexis Madrigal. It’s Martin Luther King Jr. Day, and we’re reflecting on the state of civil rights and social justice here in the United States.

Up first, we’re joined by Jelani Cobb, a staff writer at The New Yorker. His most recent book, Three or More Is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here, 2012–2025, is a collection of essays that chart the path from more optimistic times to whatever is happening today. These thirteen years, from Obama to Trump II, have been tumultuous. And nowadays, bald and open racism is alive in public American society in ways that I could not have imagined growing up or coming up as a journalist.

At the same time, we’ve also witnessed a flourishing of historical documentation, as well as powerful cross-generational activism. Here to talk with us about the movement of the storms of history, we’re joined by Cobb. Welcome, Jelani.

Jelani Cobb: Thank you. And also, I should say, I’m not in New York.

Alexis Madrigal: Oh — where are you today?

Jelani Cobb: I’m in Indiana today.

Alexis Madrigal: Oh, you’re in Indiana.

Jelani Cobb: Evansville, Indiana. Yeah.

Alexis Madrigal: Well, welcome from Indiana. Let’s talk about this arc — this arc of history. I have a friend who once said to me that the universe may bend toward justice, but the shape is definitely not an arc. So how are you thinking about it? How are you thinking about the moral universe?

Jelani Cobb: You know, my revision of that is this: I always say that Dr. King set us up with that line. He says, “The moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” There was fine print in that statement, which was that he left out the part about you having to actually get out and bend it yourself.

So it may well be bendable, and it may move in the direction of justice, but that is purely a barometer of the work that we’re willing to do to move it in that direction.

Alexis Madrigal: Looking at this set of essays, you say yourself toward the end of the book that you were a more optimistic person when you started writing them in 2012. Does that mean you have darker feelings now about the state of the arc? Do you feel like we’re just in an ebb moment and we’ll come back? What do you think?

Jelani Cobb: I think, consistent with what I said earlier about the arc, that we are certainly in an ebb moment. And it’s possible to come back, but it’s not guaranteed.

These are the moments that really test our mettle — that determine what we really believe. When I talk to my students, one of the things I point out is that nearly everyone we admire historically, nearly everyone we consider worthy of study and remembrance, earns that status for what they did in difficult moments, not comfortable ones.

So this is our collective difficult moment. And it’s the moment when we ask what kind of example we will bequeath to the generation that comes after us. That’s how I think about this.

Alexis Madrigal: Another quote from your book that I’ve been thinking about comes from W.E.B. Du Bois: “Either the United States will destroy ignorance, or ignorance will destroy the United States.”

Jelani Cobb: Mm-hmm.

Alexis Madrigal: This is tricky for me because it feels like we know more now about the true history of our nation — the founding documents, the Enlightenment ideals baked into them, as well as slavery, segregation, and all of it — than we ever have before. And yet it doesn’t feel like ignorance has been banished.

Jelani Cobb: No. And part of that is because while the information is available, the extent of its availability doesn’t reflect the degree to which we actually engage with it.

As we approach the 250th anniversary of the nation’s founding, we see versions of the American past that people want to promote that have nothing to do with what actually happened. Some people want history to function like a résumé — a long list of amazing accomplishments. But you know what a résumé never tells you?

Alexis Madrigal: Yeah.

Jelani Cobb: It never tells you what you got wrong — which is equally instructive.

Alexis Madrigal: It’s also fascinating to think about the historical examples people reach for. Looking at what’s happening in Minneapolis right now, some people — like Joe Rogan — invoke the Gestapo, the idea of people being stopped and asked for their papers.

But historians have instead pointed us to the post-1850 United States and the Fugitive Slave Act, when bounty hunters working for enslavers went into Northern cities. What do you think we can learn from our own history about what ICE is doing around the country, particularly in Minneapolis?

Jelani Cobb: When we talk about incursions into people’s freedom — about autocracy and anti-democratic practices — we instinctively look to Europe in the early to mid-20th century, as fascism took hold. And that’s a cop-out, because it allows us to avoid confronting the parts of our own history that are implicated in the same way.

That’s why the Fugitive Slave Act is such an important example. There’s a famous case from 1854 involving a Black man named Anthony Burns, who escaped slavery in Virginia and was living and working in Boston when he was tracked down, captured, and detained.

Fifty thousand people in Massachusetts came out to try to prevent him from being dragged back into bondage. And I always tell my students: this isn’t fifty thousand the way we think of it today. We can get fifty thousand people to a football game. This was fifty thousand people in a much less populated nation.

Alexis Madrigal: Wow.

Jelani Cobb: And students often say, “Oh, they were abolitionists.” And I tell them, not necessarily. If you had polled that crowd, you would’ve found a wide range of views on slavery. But what you wouldn’t have found a range of views on was whether they were willing to tolerate their neighbors being snatched out of their community and dragged away to be tormented.

If you went to Minneapolis today and conducted a poll, you’d likely find a spectrum of views on immigration. But you would not find a spectrum on whether people are willing to see their neighbors removed from their communities and taken to places where they may suffer torture — and in many cases, as reporting has shown, these are people without criminal records.

Alexis Madrigal: By ICE’s own reporting, most of them don’t have criminal records.

Jelani Cobb: Exactly.

Alexis Madrigal: We’re talking on the day the country commemorates Martin Luther King Jr. with Jelani Cobb, staff writer at The New Yorker and professor of journalism at Columbia University. His most recent book is Three or More Is a Riot: Notes on How We Got Here, 2012–2025.

We want to hear from you. What are you feeling as you think about the trajectory of civil rights and social justice today? Give us a call at 866-733-6786. The email is forum@kqed.org. On social media, we’re @KQEDForum.

I did want to go back to one moment in recent American history that feels especially instructive: President Trump’s rise to prominence through birtherism — the lie that President Obama was not American and therefore illegitimate. Why do you think that episode matters so much?

Jelani Cobb: We should actually take it a step further. The birther lie didn’t just say Obama couldn’t be president — it said he wasn’t even eligible to vote in the election he won. It called his fundamental citizenship into question.

It was part of a broader backlash against everything his presidency represented. And the race-baiting politics we’ve seen — across both Trump administrations — were predictable, given that Trump rose to prominence by attacking Barack Obama’s citizenship.

What that did, very plainly, was say: this person is illegitimate. This person does not belong. Even though it was factually false, it was a way of metaphorically saying that Obama was not American.

And the fundamental question in this country, especially along racial lines, has always been whether Black people could be both Black and citizens at the same time. What we saw then harkened back to that long tradition — and foreshadowed what came next.

Alexis Madrigal: Did you know at the time, when you saw that happening, that it was as dark a sign as it turned out to be?

Jelani Cobb: Yes. I had been covering this history. I had been teaching it. I don’t say that to claim clairvoyance, but people did think I was being alarmist when I talked about what he represented. Unfortunately, that assessment has been borne out.

Alexis Madrigal: Here we are on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, reflecting on the state of civil rights and social justice with Jelani Cobb, staff writer at The New Yorker and dean of the Columbia Journalism School.

We’re taking your calls and comments at 866-733-6786. That’s 866-733-6786. The email is forum@kqed.org.

I’m Alexis Madrigal. Stay tuned.