This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Alexis Madrigal: Welcome to Forum. I’m Alexis Madrigal. I have to admit, I’ve been fascinated by neural networks since I was a kid. I read a Scientific American article in January 1996 about using neural networks to understand animal locomotion, and I was hooked. The connectionist paradigm, as it was known, argued that cognition wasn’t based on fancy symbolic logic or some hardwired rule set, but rather emerged from the unimaginably complex and numerous connections among our billions of neurons. That school of cognitive science has since emerged victorious, helping to spawn the AI boom as we know it.

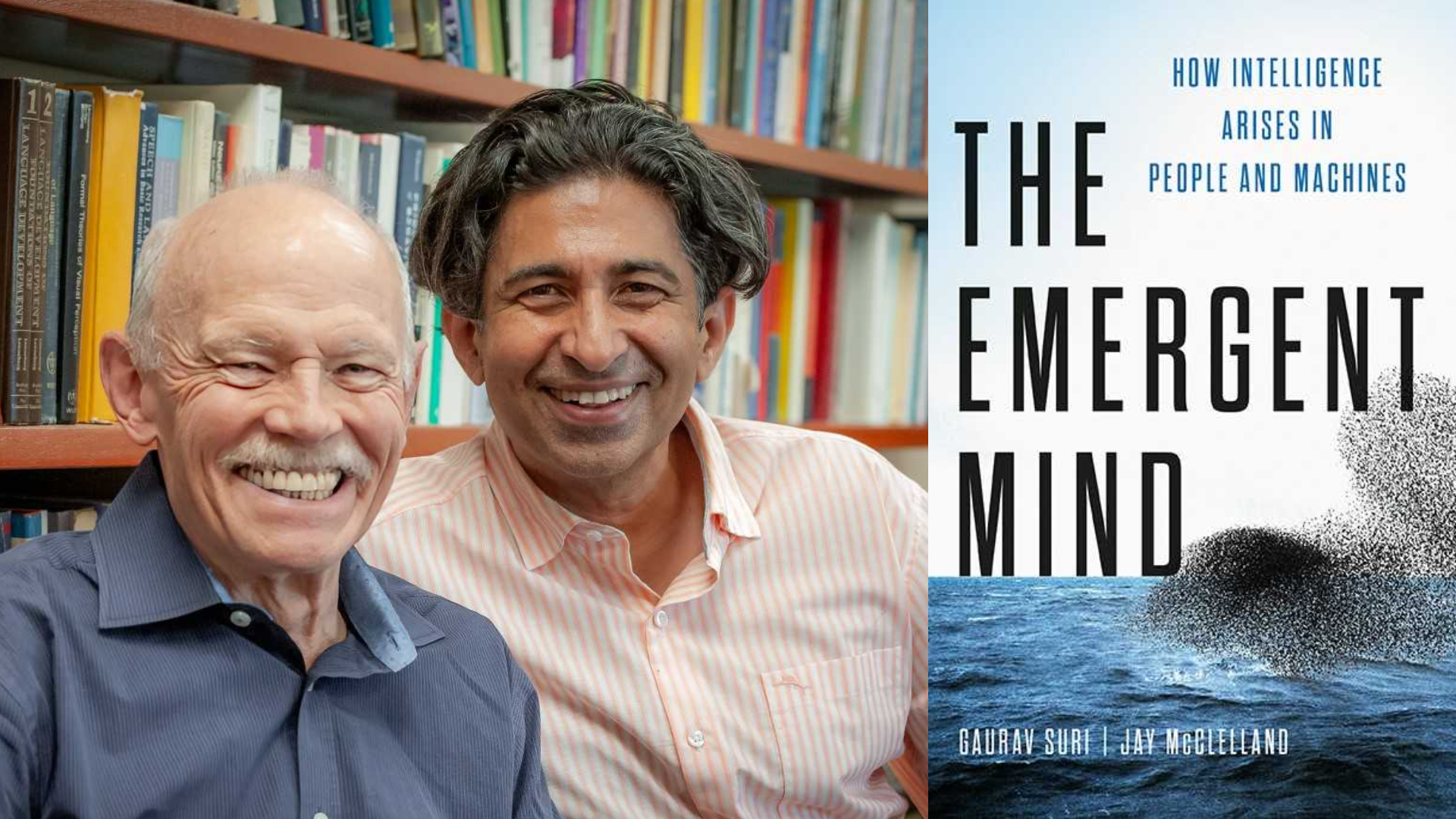

Stanford’s Jay McClelland was a party to and witness of much of this history, and he joins us along with his co-author of a new book, The Emergent Mind, Gaurav Suri, himself a professor at SF State. Thanks so much for joining us.

Jay McClelland: Thanks for having us, Alexis.

Gaurav Suri: Pleasure to be here.

Alexis Madrigal: Let’s start with the basics. We’re going to spend a bunch of time this hour talking about what neural networks are—starting with human beings. So in a human brain, what exactly is a neural network, Jay?

Jay McClelland: A neural network is essentially a network of simple units that interact with each other to support our cognitive activity. We think of these simple units as sort of like ants—little things that aren’t individually intelligent but, when they work together collectively, give rise to our emergent intelligence.

Each one of these eighty-six billion neurons in your brain has connections to up to a hundred thousand other neurons. They receive inputs from many other neurons and send signals out to many more. These inputs can encourage a neuron to become more excited, to quiet down, or modulate the influence of others. The key idea is that each neuron integrates many signals and, in turn, influences many others.

Alexis Madrigal: Right.

Jay McClelland: They work together collectively in a way that’s so extensive because of this massive interconnectedness.

Alexis Madrigal: Yeah, it’s so interesting. Gaurav, when we model neural networks or represent them in a paper, they often get simplified—maybe to six units or so. Could you walk us through how a very simple version of this works?

Gaurav Suri: Happy to. First of all, a model should be simple. The purpose of a model is to help us understand a complex phenomenon. If your model is as complex as the thing you’re trying to study, it’s not going to help.

There’s a beautiful story by Borges, the Argentinian writer, who imagined a city of mapmakers whose maps became so precise that they ended up being as large as the land they described. So of course, a model should be simpler.

Now, imagine a simple neural network at work: You get up and go to the refrigerator. Someone asks, “Why did you go to the refrigerator?” You might say, “Because I’m thirsty.” But underneath that, neurons that detect thirst—perhaps due to higher salt levels in the bloodstream—start activating. Through experience, those neurons have become connected to others that initiate the action of moving toward the fridge.

Ultimately, your muscles are connected to neurons that signal each other with electrical and chemical messages. This chain of activation gets you off the couch and to the fridge—and it also shapes the story you tell yourself about why you did it.

Alexis Madrigal: Don’t forget the boredom unit and the “Warriors game is on” unit, both pushing you toward the fridge. That’s part of the complexity, right? We’re influenced by all these different contexts.

Gaurav Suri: Exactly. That’s the beauty of neural networks—they allow for all these currently active factors, like the Warriors game, to influence decisions. It’s not a symbolic “if this, then that.” It’s a confluence of forces coming together to shape action.

Jay McClelland: Yeah.

Alexis Madrigal: Jay, we’re not going to tackle the hard problem of consciousness exactly, but how do these very simple processes lead us to experience such complex thoughts and rich sensory worlds?

Jay McClelland: A lot of people imagine there’s a little man in the head—a kind of homunculus—watching the movie of our thoughts in a Cartesian theater. But the perspective we take is that our conscious experience arises from the distributed and integrated pattern of activity across multiple brain areas simultaneously.

Leading theories now suggest that cognitive control isn’t located in a single module, say in the frontal lobes, but rather in a distributed network of brain areas integrated with others that perform more specific tasks, like responding to visual input, processing sound, or controlling the muscles of the hand. These networks orchestrate the process of navigating through the world and generate the integrated, multimodal experience we feel as thought.

Alexis Madrigal: Let’s play with a simple example on the perception side. What’s going on in my brain when I try to read this sentence on my iPad?

Jay McClelland: It’s a very rich and interactive activation process. My late colleague, David Rumelhart, really pinpointed this. Dave was one of the first people to explore how neural networks could help us understand cognition—how we interpret written or spoken language.

He argued that every aspect of our interpretation of sensory input influences all the others. When we see a printed word like “the,” the visual features—lines and shapes—get activated. Dave even modeled letters as combinations of fourteen different line segments, so that even if some features were missing, you could use context to fill in the rest.

Alexis Madrigal: Like when your old calculator was running out of batteries.

Jay McClelland: Exactly. Or when a neon sign has some lights out—you still know what it says because your brain fills in the missing parts.

When we modeled this, we postulated feature units for visual components, letter units for each position in a word, and whole-word units. These layers are bidirectionally connected. If the features resemble a “t,” that activates the “t” unit. If the input is ambiguous, multiple possibilities activate partially. When the letters fit together to form a recognizable word, that word’s activation strengthens—it essentially says to the others, “I’ve got this.” It also sends feedback down to reinforce the features and letters that support it.

This interactive process helps a familiar word hold in your perception longer than a random string of lines.

Alexis Madrigal: Exactly! That’s why, when you’re used to someone’s handwriting—especially your own—you can read things that barely form letters. You just know, “That’s how I write ‘the,’” even if the “h” looks off. That’s the incredible flexibility of the human mind.

Gaurav Suri: Right. One of the first models that really drew me in was this letter-reading model. I actually did my PhD in midlife, and Jay was teaching me this model. I found it so beautiful because it showed activation as the common currency—the flow of activation brings things into focus.

What became clear as I traced these activations is that top-down expectations—what I expect the word to be—and bottom-up inputs—what my eyes actually see—combine to shape perception. That ambiguous symbol Jay mentioned could be an “h” or an “a.” If it’s in “the,” it’s an “h.” If it’s in “cat,” it’s an “a.” That interplay is what makes perception possible.

Alexis Madrigal: That’s beautiful. We’re talking about how neural networks work—first in humans, and later in AI—with Gaurav Suri from SF State and Jay McClelland from Stanford. We’ll be right back.