This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Alexis Madrigal: Welcome to Forum. I’m Alexis Madrigal. Because the Bay Area has produced so many legendary figures during the ferment of the 1960s and ’70s, we often talk with an older generation of leaders in the broader multicultural landscape.

Julian Brave NoiseCat, though, is the next generation — a kid who grew up in the very institutions those earlier leaders built, learning the traditions they carved and embodied from the histories of their communities. For example, he became a champion powwow dancer, learning in Oakland and traveling the national circuit. But he’s also spent a life dealing with the fallout and trauma of that earlier generation’s drive for freedom, especially through his father, the artist Ed Archie NoiseCat. It’s hard to be the child of a legendary figure sometimes.

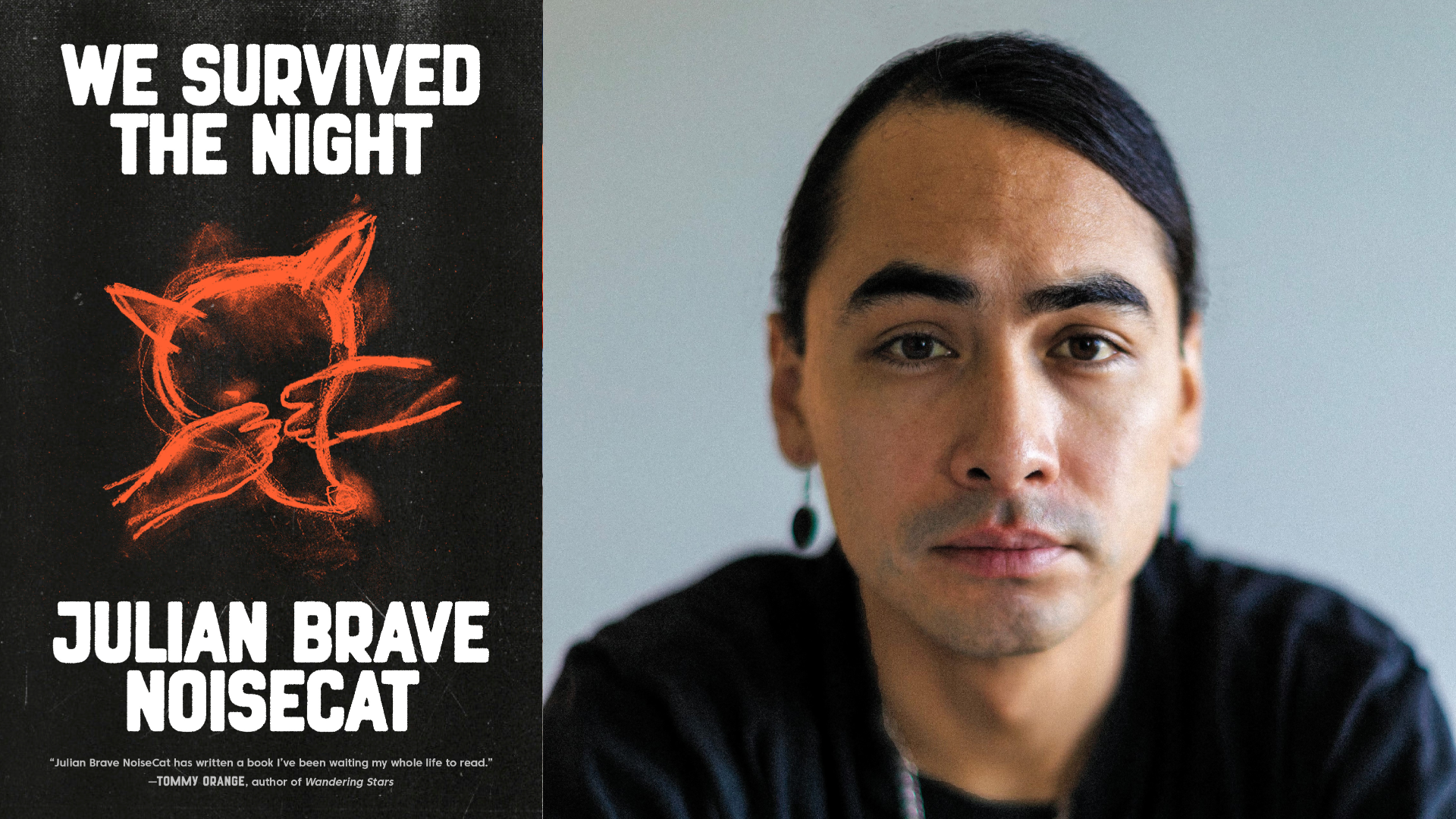

NoiseCat’s new book is We Survive the Night, and he joins us this morning. Welcome.

Julian Brave NoiseCat: Thank you so much for having me, Alexis.

Alexis Madrigal: So this book is, at least in part, a personal history of an Indian kid of divorce growing up in Oakland. Your mom is Alexandra Roddy, non-Native; your dad, Edwin NoiseCat, is Native — from a tribe in British Columbia. Just give us the setup. Who are they?

Julian Brave NoiseCat: I grew up in Oakland, California — a child of two worlds. My father is a full-blood First Nations man from British Columbia, Canada — so fully Native. My mother is an Irish Jewish New Yorker. And if you hear her talk, she sounds the part. Some of my cousins on my Native side joke that when my mom talks, it sounds like the TV.

So, I really was a child of two worlds, and I grew up in a place — Oakland — that celebrated figures and movements that cut against the grain and pushed boundaries, like the Black Panther Party and the United Farm Workers. In my corner of the Native Bay Area, it was the Indians of All Tribes and the 1969 occupation of Alcatraz — a game-changing moment for Native people and a part of American history that’s still broadly overlooked, even here in the Bay Area.

Alexis Madrigal: Yeah. How did your dad fit into that whole space?

Julian Brave NoiseCat: The Bay Area has a lot of love, especially among its hippie-generation types, for a certain image of American Indians. My dad — just to give your listeners a picture — has the thickest and longest mane of hair you’ve ever seen. Truly mythic.

Alexis Madrigal: I’m jealous.

Julian Brave NoiseCat: Me too! Honestly, it’s hard to be his son sometimes. He’s got these huge, mythically proportioned hands, and he’s an artist with the most Native name you could imagine — maybe other than mine — Edwin Archie NoiseCat.

We moved to Oakland when I was about three years old, so I really did grow up there all the way through high school. My dad was this figure — the coolest dad at preschool. All the other parents wanted to be friends with him.

Alexis Madrigal: Wow. I mean, when you’ve got that kind of situation — particularly when you’re little — I assume he seemed like a heroic figure to you. You must’ve really lionized him.

Julian Brave NoiseCat: When I was very little, yes, absolutely. My mother had a corporate job, so my dad, being an artist, was at home. I’d hang out with him in his studio.

Artists go on all kinds of adventures — meeting the guy who does their silverwork, picking up wood for carvings, things like that. Even just hanging out in a carver’s studio is a real vibe. There’s rock and roll playing — Neil Young, Led Zeppelin — while he’s chipping away at a wood block.

Honestly, though, he really loves listening to NPR. He likes to joke that he’s an “NPR Indian,” and he even has this whole bit about what NPR would sound like if it were hosted on the rez.

So that was my childhood — hanging out with him in the studio, riding around in the back of his big red powwow van, watching The Land Before Time on the VHS player, and traveling to art shows across North America. Despite being half Native and half white, if you looked at a photo of me, my dad, and my mom, you’d say my dad’s genes kicked my mom’s genes’ butt. People called me “Mini Ed.”

But a few years after moving to Oakland, my parents divorced. My father fell back into alcoholism, something he struggled with much of his life. He moved away to Santa Fe, New Mexico — kind of the Mecca of Indian art in the U.S., where all the silver and turquoise in the world seem to be.

Alexis Madrigal: I imagine, given the setup you just gave about your relationship with your dad, that when he left there was an incredible sense of loss. And your mom did what she could to keep you connected, yeah?

Julian Brave NoiseCat: My mom did way more than you’d ever expect of any parent. She describes it as instinctual. Suddenly she was alone, with this kid who was obviously hers — but also obviously half Native, with a really Native name. Nobody looks at “Julian Brave NoiseCat” and wonders what my background is.

On top of the emotional break that happens when a son loses his father at that formative age — when dads still seem like superheroes — it was devastating. She went through her own thoughts of suicide. It was a dark, hard time for both of us.

But she understood, instinctually, that she needed to keep me connected to his family — over a thousand miles away on the Canim Lake Indian Reserve, a 24-hour drive from Oakland — and to my community here in the Bay Area.

Interestingly, it was after my father left that I started going to the Intertribal Friendship House on International Boulevard in East Oakland. It’s still there — the third-oldest urban Indian community center in the country. It was even involved in planning the 1969 Alcatraz occupation.

When I was a kid, they held powwow drum and dance practice on Thursday nights — now it’s Wednesday nights. I remember going there with my white mom, sitting around the circle, scared to get up and dance.

Alexis Madrigal: Oh, man. What was that like for you? Did you try to sneak in alone, or walk in holding her hand? What was your approach?

Julian Brave NoiseCat: Looking back, I wasn’t the only Native kid there scared to step into the circle. Even without being half, it can be intimidating to step into your culture sometimes. Some kids are brought into the dance circle in Pampers — that’s just what they know. But for those of us who choose to step in later, it’s daunting.

So we’d run around outside instead — a bunch of Native kids playing in the sandbox or on this janky old play structure that could definitely give you tetanus — just avoiding the gentle pressure from the elders who wanted to see us sing or dance.

Eventually, though, I did.

Alexis Madrigal: What got you in there? What got you into the circle?

Julian Brave NoiseCat: Honestly, it was my mom’s partner after my father left — a guy named Koko, from the White Mountain Apache Reservation. He walked up to my mom at the Intertribal Friendship House one day, during a birthday celebration, and asked what tribe she was from. She’s witty — a New Yorker — so she said, “The white one.”

Koko was a smooth criminal, in certain ways, but deeply knowledgeable about his Apache culture and Native culture more broadly. He was a fluent Apache speaker. If you go to the White Mountain Apache Reservation today, it’s still one of the few places in North America where you’ll regularly hear the language spoken.

He came from the people of Geronimo — proud warriors, some of the last to lay down their arms against the U.S. government. Koko had become a kind of intellectual or renaissance man. Canyon Records, the label that publishes Native music — northern drum groups like Northern Cree — would send him CDs to review.

He really knew his culture. And in that moment when my father was gone, he helped me come back into mine — and encouraged me to step into the dance floor.

Alexis Madrigal: Beautiful. We’re talking with author and filmmaker Julian Brave NoiseCat. His new book We Survive the Night just came out yesterday. He grew up in Oakland, as you’re hearing. We’ll be back with more from him after the break.