This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

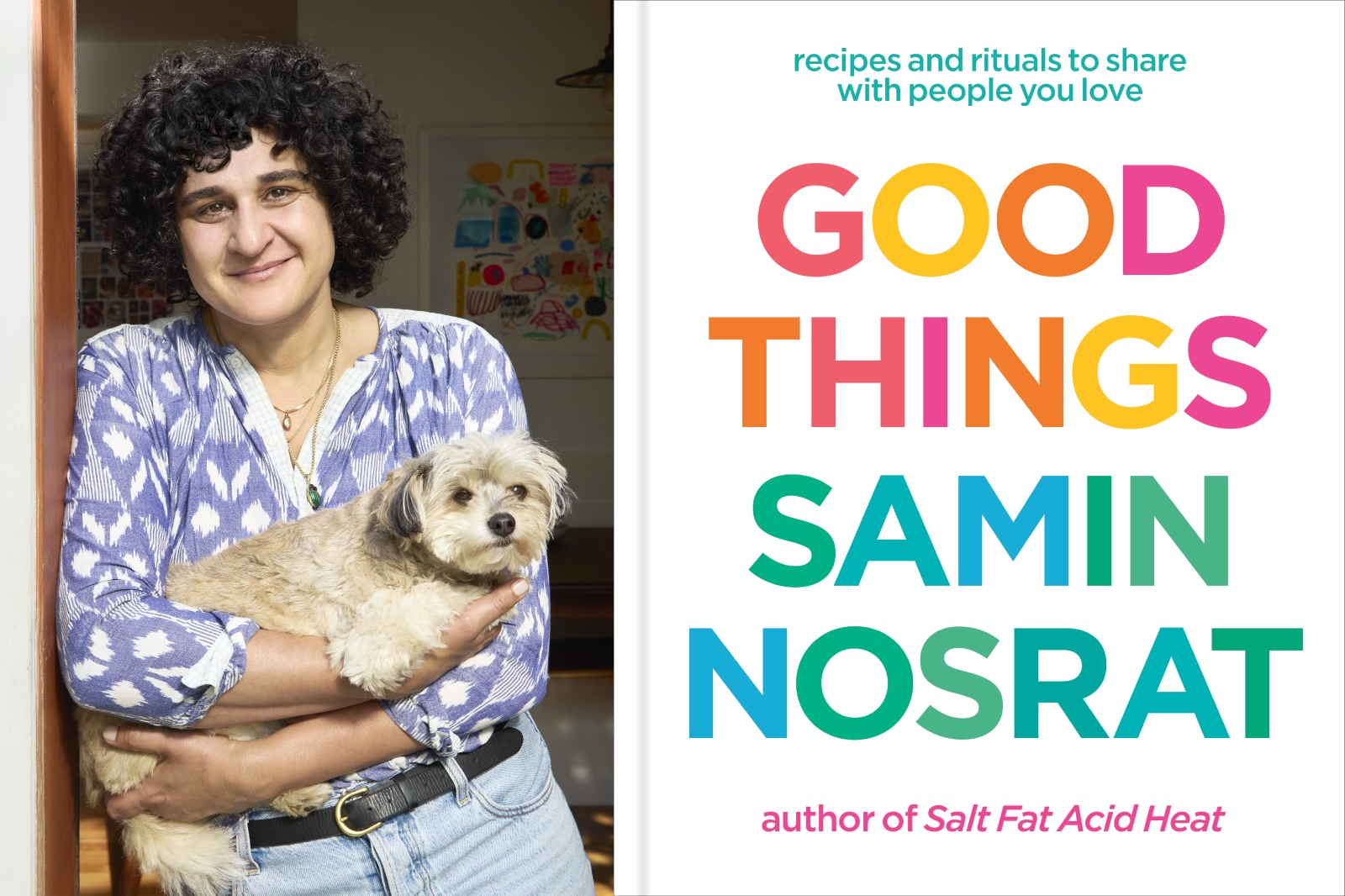

Alexis Madrigal: Welcome to Forum. I’m Alexis Madrigal. Today, we’re talking with Samin Nosrat, the bestselling author of Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, and her new book Good Things, which is about the rituals we use to ground ourselves in community and the food that helps glue us together. Welcome to Forum, Samin.

Samin Nosrat: Oh, I like that. We’re just gluing ourselves to our food.

Alexis Madrigal: Hopefully not literally with the food. So, Samin, this is kind of an unusual thing for both of us. You’ve been touring this book all around the country, talking about this incredible ritual, Monday night dinner. And I also do this show all the time and usually have never met the guests before they come into the studio and sit where you are.

This morning is a little different for both of us because I’m one of the people who does Monday night dinner with Sarah, my wife, and my kids — and you. We’ve been doing this weekly dinner for four years. So, we’re not going to talk about our friendship the whole time, but I have to ask this first: What’s the worst thing I’ve made for you over the years that you’ve had to eat? You can be honest, but maybe not too honest.

Samin Nosrat: I don’t know… I don’t think about the food that way. If you’re really pressing me, I feel like there was maybe a time we were cooking a whole fish.

Alexis Madrigal: Yes, that’s it. I have it written right here: a half-cooked, bony grilled fish. I didn’t want to overcook it because that felt like an amateur move, so I undercooked it.

Samin Nosrat: I feel like you get the raw deal — oh, no pun intended — a lot of the time. Because there’s this way where I’m just like, “Alexis can grill it.” So you get stuck cooking things that I actually feel kind of self-conscious or a little insecure about cooking well myself. A lot of the time you get burgers, and I actually think burgers are one of the hardest things to cook.

Alexis Madrigal: Tough. Yeah.

Samin Nosrat: To get them right on the inside — and every batch of ground beef is different. But you do a great job on burgers.

Alexis Madrigal: Oh, shoot. Thanks so much. Judy Campbell, our producer, said I was fishing for a compliment with that first question, and it turns out she was right.

But you know, there are serious things happening in the world. The government is shut down. It’s a hard time for many people in our communities. And the epigraph of this book Good Things is: “Eating is a small good thing in a time like this.”

Samin Nosrat: Mhmm.

Alexis Madrigal: When did you land on that epigraph?

Samin Nosrat: It’s always “a time like this” for me, or for someone around me. That’s what dawned on me. The quote comes from a Raymond Carver story that’s really sad and heartbreaking — about parents losing a child.

I’ve gone through a lot of loss myself in the last several years. Inside of that, I was trying to make a book and communicate what I feel like I’m known for — joy in cooking. But I wasn’t feeling that joy, so I had to find my way back to it and back to some meaning in this thing I do. Honestly, these dinners that we stumbled into together really gave me that.

They are, in so many ways, just the smallest thing. It’s not a grand event. It’s not a hugely fancy meal. It’s not that anyone has spent all week preparing. It’s just these small gestures. I began to collect those gestures, and that’s what the book became.

I also think it’s important to acknowledge that eating can be a small good thing in a time like this — but it’s not always a small thing. There are people in the world right now who are being forcibly starved. Food is also very powerful — it can be a political tool, and it can also be a way for us to share small moments of connection.

Alexis Madrigal: And you kind of weave that into the rituals of community, but also even the way you talk about food in here. One piece of this book I really love is when you’re talking about those daily or weekly rituals of food making. What are a couple of those? Because I feel like some have made their way into my life as well.

Samin Nosrat: I have so many funny little quirks in my own cooking life, partly because I’ve had a really counterintuitive arc as a home cook. I grew up in my mom’s kitchen — she was always cooking. Then I went to college and made English muffin pizzas.

Alexis Madrigal: Like us.

Samin Nosrat: I always say I excelled at the “carbs and cheese” category. Then I stepped into Chez Panisse and was suddenly cooking and learning from world-class chefs. It’s only in the last ten to twelve years, since leaving professional kitchens, that I’ve really come into my own as a home cook. I live by myself, so I still eat a lot of the kind of stuff people don’t usually admit to.

Alexis Madrigal: Wait, like what?

Samin Nosrat: Like tonight’s dinner will just be a bunch of grapes, or “single person food.” I eat a lot of those meals. A big part of the project with this book was believing those little funny things I do — that make me so happy, whether for myself or a few others — are worth sharing and not an embarrassment.

Some of my rituals include adding cardamom seeds to my coffee before grinding in the morning, which brings this amazing smell. Every year I make apricot jam — I go down to Andy’s Orchard in Morgan Hill, pick apricots, and make jam. The Monday dinners anchor my week. Sometimes I think in advance about what I’ll make, and now we even have annual things: I know with whom I want to eat Dungeness crab or the first wild salmon of the season. And sometimes it’s just my personal quirks, like, “It’s been a while since I made myself a tuna melt in the toaster oven.”

Alexis Madrigal: Yeah. And some of it ties back to your first book, which people have described — maybe even you — as a manifesto against recipes. This new book also plays with the idea of what a recipe is, the different formats it can take. You want to give people enough of your ritual, but not too much, right?

Samin Nosrat: Exactly. It’s not only the ritual. There’s a wonderful quote from poet and pie maker Kate Lebo, who lives in Spokane. She wrote The Book of Difficult Fruit and describes recipes as “rituals that transform.”

I’ve had a lifelong struggle with recipes because they make an impossible promise: follow the words on the page, and you’ll get the same result every time. That’s not true. If I make tomato sauce today and again next month, the tomatoes are different, so the sauce is different. My stove and pots are different from yours.

So I had to redefine what a recipe meant for me. I loved the idea of ritual as transformation. I want to serve the home cook by teaching enough to give confidence and information, but not confining them. Sometimes you need precision — like a chili crisp recipe where spices are listed in grams. Other times, it’s just a paragraph describing something I do or saw a friend do.

For example, my neighbor Aya Brackett — who photographed the book — was making carrot and cucumber sticks for her kids, with just seasoned rice vinegar and flaky salt. Suddenly, I was fighting her six-year-old for them because they were so good. I thought, “People need to know about this.” But what was I going to write? “Two carrots, peeled and cut into sticks; one teaspoon rice vinegar”? The story was more useful.

With vegetables, too — we buy them when they look good, not with a strict recipe plan. So I created the vegetable chapter to give people freedom.

Alexis Madrigal: So instead of “roasted carrots with marinated feta,” you give people a primer — boiling, roasting, sautéing — then a set of options.

Samin Nosrat: Exactly. And in each season, I built matrices of options. People get stuck making the same cookbook recipe over and over, like Yotam Ottolenghi’s eggplant with pomegranate seeds. I wanted to connect the dots — to show that once you’ve made it fifty times, you actually have the tools to create many new dishes.

So the book gives you the basics — roasting vegetables, making condiments — and shows you all the ways to combine them. I even tested the flowcharts by sending them to friends, saying, “See if you can make something gross with this.”

Alexis Madrigal: We’re talking with chef and author Samin Nosrat, Oakland’s own, bestselling author of Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, and now Good Things. Listeners, share a wrong opinion you have about food with Samin. Call 866-733-6786. That’s 866-733-6786. Or email us at forum@kqed.org. We’ll be back with more right after the break.