This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

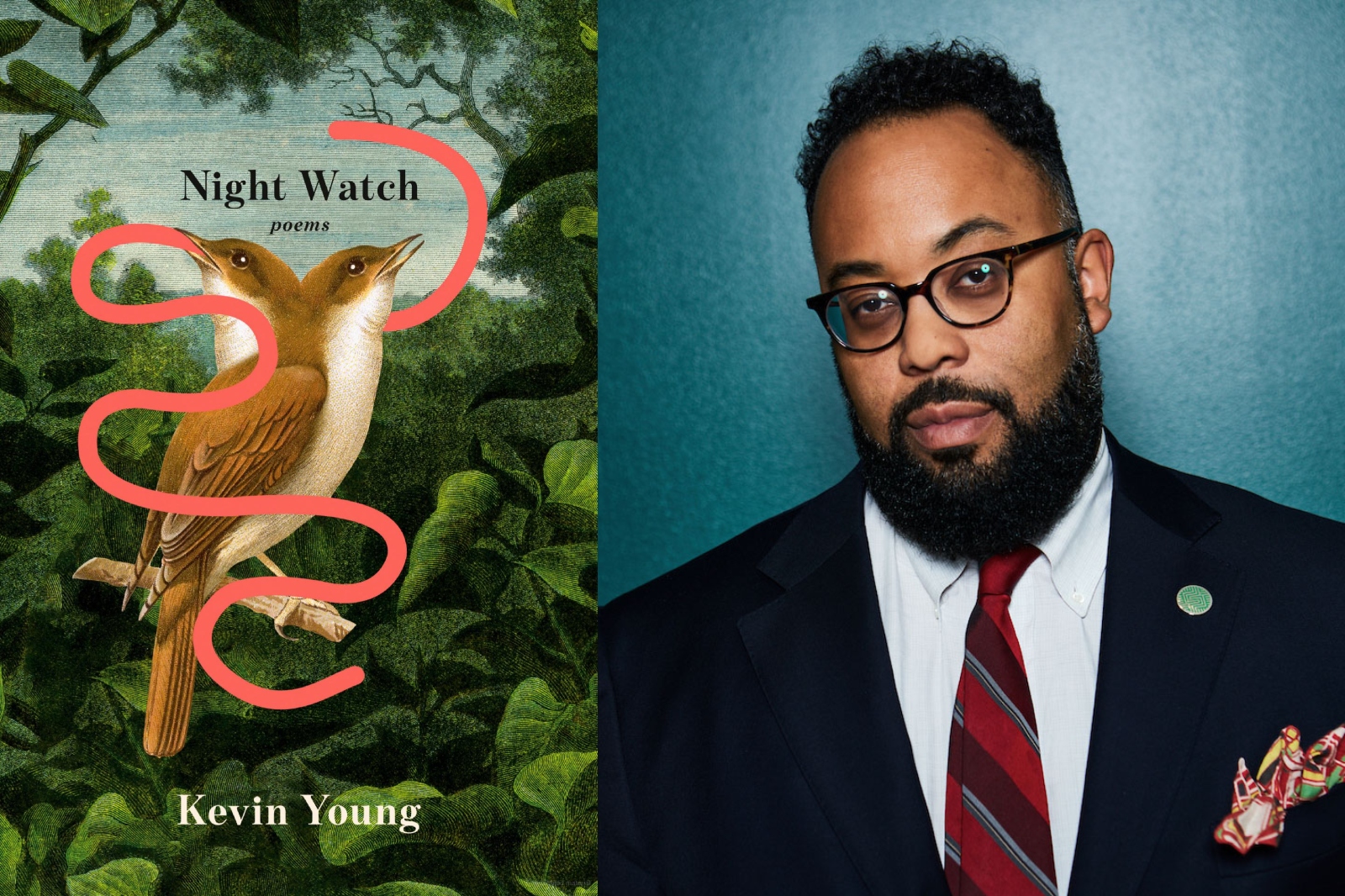

Grace Won: Welcome to Forum. I’m Grace Won, in for Alexis Madrigal. Poet Kevin Young has called poetry the most efficient mode of time travel. In his new volume of poetry — his thirteenth — Young travels back in time to tell the true story of conjoined twins born into slavery, stolen from their parents, and paraded as a carnival sideshow. He also documents other journeys, like the passage through death, grief, and resurrection, in a series of poems inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy.

“It’s like a language, loss,” he writes, “learned only by living there.”

Young is the poetry editor for The New Yorker magazine. In addition to his own poetry, he’s edited ten anthologies, including A Century of Poetry in The New Yorker, which celebrates the magazine’s one hundredth anniversary. He’s also the author of three nonfiction books, including The Grey Album and Bunk. His children’s book Emile and the Field was named one of the best children’s books of the year by The New York Times.

He’s a Harvard graduate and spent time in the Bay Area as a Stegner Fellow at Stanford. He’s a podcast host and the former director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. And best of all, he’s here with us today on Forum. Welcome to the show, Kevin.

Kevin Young: Thanks for having me.

Grace Won: You’ve said that being a poet was the only career you ever wanted, and you knew that as a young kid. What was it about poetry that drew you in?

Kevin Young: Yeah. It’s more like a calling, I think. You find yourself drawn to language, but I also loved the stories my family told in Louisiana. Both sides of my family are from Louisiana and have been on different patches of land there for almost two hundred years. Having that rich history and hearing how they told stories — which was, believe you me, not in a straight line — makes one a poet.

I often say: on one side of my family are preachers, on the other side, musicians. And somewhere between that preaching and that music is poetry.

Grace Won: Absolutely. I read this cute story of you seeing one of your first poems published by a teacher on mimeographed pages. People of a certain age will remember how dittos would come off the machine, with that distinct scent.

Kevin Young: It smelled so good.

Grace Won: Yes, it was a sensory experience. So when you saw your words on that page, did you just bloom?

Kevin Young: Yeah. The interesting thing was my name wasn’t on it, and I think that was just as important. The teacher — Tom Averill, who I’m still friends with and who’s a wonderful writer himself — would pass them out typed up, and like the miracle of mimeograph, suddenly they were there the next day. But he wouldn’t put your name on it.

That secret thrill was actually what drew me to poetry. It was always bubbling around, but to be able to say, “Oh, I made something and someone read it, and they don’t even know it’s me” — there was something really exciting about that. It was a powerful experience to connect to words and language.

My first poem, I think, was actually about a trip to the underworld — something about Egyptian lore of the dead. So to be writing about death and the underworld in this new book, Night Watch, is a strange kind of full circle.

Grace Won: Young Kevin, you didn’t know Dante’s Inferno would come to pass for you. You’ve mentioned your family from Louisiana — this long family tree of speakers and singers and preachers. But your father was an ophthalmologist, your mother a chemist, and you moved often for their educational paths, settling in Kansas by age ten. When you announced you wanted to be a poet, what was the reaction?

Kevin Young: Immediate worry. I didn’t really announce it, which was the smart thing. I was doing other things and sort of snuck it in there. My parents wanted me to be well-rounded, so it was just another thing. But to be honest, they were really supportive.

I also kind of made it so I was writing about them, especially early on — about life in Louisiana. This new book begins with a poem set there and is dedicated to three of my relatives: two of my aunts and my grandmother, who passed away in the past couple of years. My grandmother lived to be 101. That was such a blessing, to have her that long and to know the stories she held.

I’ve always felt a responsibility to tell those family stories, to carry the torch of witness. Poetry can do that better than anything else.

Grace Won: I want to give the names of the women — evocative names in themselves.

Kevin Young: Yes. Tootie was my aunt, named so by my father. That was her nickname, and I don’t think I knew she had another name until I was much older. Mama Annie was my grandmother, my mother’s mother. And then Gail was my father’s other sister, who passed away.

Grace Won: You’ve been working on the poems in Night Watch for decades. There’s a list at the end of the book with dates and places starting from the spring and summer of 2007. In the meantime, you’ve published many other volumes of poetry and prose. What about these poems wasn’t ready for daylight?

Kevin Young: Books take a while, and poems can too. The collection is structured in four sections, beginning with one poem. Each section gets longer, and it ends with a Dante sequence. That sequence really made it into a book.

I had ideas and starts, but focusing them through this journey — through the underworld, into something that looks a little like paradise — helped shape it.

I started the book shortly after my father died. I wrote other poems about his life and death, but this was a way to write around that, from another perspective, to think about us all. I put it away because it seemed too dark. But during the pandemic, I pulled it back out. The colossal losses we were all experiencing made it feel relevant.

Even the poem about Millie-Christine, the conjoined twin you mentioned, who called herself “I” or “we” at different times — her doubleness, her division, seemed to reflect our nation as well. She lived through the Civil War after being stolen as a child. That felt relevant too. So the timing ended up feeling right.

Grace Won: Right on time. Before the break, I want people to hear your voice. Let’s take an excerpt from Cormorant, which is evocative of a bird but also about your father. Could you read a little of it?

Kevin Young: Sure. This is from Cormorant.

…Black swan, you flood

back to me among

the memory of my father

driving home, his hands a map

pointing out shacks where Negroes

once lived, now

only timber, & anger, still there

for him forever. Besmirched

crow-cousin, dirty seraph,

today, you are enough—

you’ll do—if only

I could see you again, hungry,

waiting, at the edge of the bayou.

Grace Won: That was Kevin Young reading from his poem Cormorant. His new volume of poetry is Night Watch. Young is poetry editor of The New Yorker and also editor of the anthology A Century of Poetry in The New Yorker: 1925–2025.

We’re speaking with Kevin Young about his book and what it means to be a poet. And we want to hear from you: What poems or prose have helped you navigate grief, death, or loss? Are you a poet, or maybe a poet in the making? What inspires your work? And do you have questions for Kevin Young? He is the poetry editor of The New Yorker, after all.

Call us at 866-733-6786. Email forum@kqed.org. Find us on Bluesky, Instagram, or @KQEDForum, or join our Discord community.

I’m Grace Won, in for Alexis Madrigal. More from Kevin Young and his new volume of poems, Night Watch, after this break.