This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Alexis Madrigal: Welcome to Forum. I’m Alexis Madrigal. Seems like every big city has an area that, for one reason or another—usually a mix of rascally charm and cool history—becomes a magnet for outsiders. You know, Pike Place in Seattle is a great example.

Here in San Francisco, the tricky thing is that at Fisherman’s Wharf, the very shops and restaurants set up to serve hordes of tourists often drive away locals, not to mention the people still catching fish and working on the Wharf. Now, there’s a big plan to start remaking the area. How do you balance the needs and desires of such different groups of people? That’s our question this morning, and here’s who we’ve got to answer it.

Elaine Forbes is executive director of the Port of San Francisco. Welcome.

Elaine Forbes: Thank you so much.

Alexis Madrigal: John King is author of Portal: San Francisco’s Ferry Building and the Reinvention of American Cities. He’s the former urban design critic for The Chronicle. Welcome back, John.

John King: Thank you.

Alexis Madrigal: And we’ve got Sal Alioto, captain of a historic fishing and tour boat, the Golden Gate, based at Fisherman’s Wharf. Welcome.

Sal Alioto: Good morning.

Alexis Madrigal: John, let’s start with you. Talk a little about the history of Fisherman’s Wharf and what we see there today. First, though, when’s the last time you had clam chowder on the Wharf waterfront? How was it?

John King: The last time I had clam chowder on the Wharf waterfront was about two years ago, and it was terrible.

Alexis Madrigal: Right. That’s kind of the thing. When we go to Fisherman’s Wharf, we expect fresh fish. The boats are right there, the fish is coming in—but that’s not exactly how it works at Fisherman’s Wharf.

John King: There are great restaurants there, but I’m thinking of walking up to one of the crab stands, realizing I’d never tried it even though I grew up in the Bay Area. I tried one, and I thought: back to Scoma’s next time.

Alexis Madrigal: So tell us a little about the history there. You’ve written about it, and you also grew up spending time around the Wharf.

John King: Yeah. In a nutshell, North Beach was North Beach because that’s where the beach was. It was an Italian neighborhood, and a lot of fishers settled there as the city grew just a little to the north. After World War I, you started to have more travel and tourism.

Locals went there for great fish, great views, and the funky, ramshackle feel that San Francisco has always cherished. But even back then, tourism was growing. The WPA Guide to San Francisco in 1940 said: Twentieth century commercialism and old-hand tradition go hand in hand at Fisherman’s Wharf, describing neon-lit shops across from nets hanging over the docks.

So even back then, people wanted authenticity, and merchants wanted to capitalize on that. That tension has been there for ninety years.

Alexis Madrigal: Yeah. And Sal, your family name is Alioto—hard not to notice that at the Wharf. What’s your family’s history there?

Sal Alioto: My grandfather, Antonino Alioto, came from Porticello, Sicily, in 1900 as a sixteen-year-old boy. He left his family, landed at Ellis Island, and came across to San Francisco, where he had an aunt and uncle.

It’s hard to imagine a sixteen-year-old boy—really, a young man then—coming to San Francisco and starting his career as a fisherman. He lived on Mason Street, at what was basically the beginning of Meiggs Wharf, which eventually became Fisherman’s Wharf. He had a felucca, a kind of fishing boat before the Monterey boats we see now. His was called the Giuseppina, which means Josephine. That’s how he started in the fishing industry.

Alexis Madrigal: Is it fair to say you grew up on the docks there?

Sal Alioto: Yes. Very much so. I vividly remember being a little boy, sitting on top of the nets my grandfather was preparing. I thought I was king of the mountain. He’d wheel me down in an old fishing cart as he prepared to mend nets. That’s where I started to learn. He’d hand me a needle and teach me the craft of mending nets—something that’s stayed with me all my life.

Alexis Madrigal: When did you know you’d become a fisherman yourself?

Sal Alioto: I can’t pinpoint exactly. I had a typical North Beach childhood—living on Powell Street with my aunt and uncle on the middle floor and my grandfather and another aunt and uncle on the top floor. I didn’t really start fishing seriously until just before graduating high school. That’s when I realized: this is what my grandfather did, what my dad did, and it was the natural step for me.

Alexis Madrigal: So before we talk with Elaine about the transformation of Fisherman’s Wharf, tell us: in your life, what changes have you seen there, especially in the last five or ten years?

Sal Alioto: A lot has changed, especially the people who come to the Wharf. When I was younger, people dressed up to go there. It was an event: you went to Alioto’s, Tarantino’s, Castagnola’s. You made a night of it. That’s not the case now. It’s a different world, a different generation, and you see a very different clientele.

Alexis Madrigal: Elaine, as executive director of the Port of San Francisco, you want to invest in this place, make sure it serves all these groups, while honoring its legacy. Where do you start? Tell us about the plan.

Elaine Forbes: We start with strategic investments to keep the area as vibrant as possible. The Wharf has been heading toward a pivot point for some time, and the pandemic really pushed us there.

Sal mentioned the large restaurants that flourished in the 1970s. Generations of San Franciscans and visitors enjoyed them, but they’ve been declining. The era of big, white-tablecloth restaurants has passed. The pandemic forced many families not to reopen.

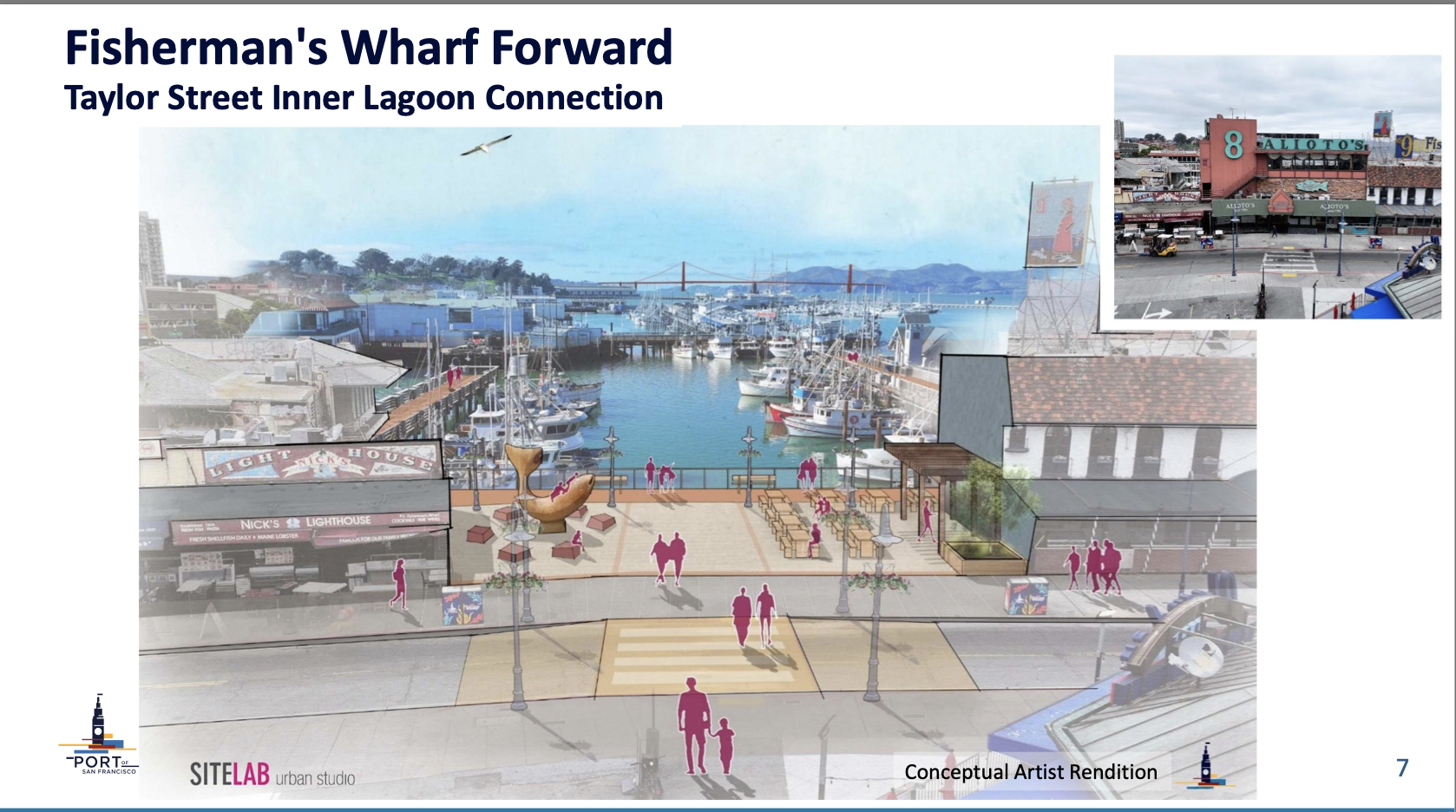

So we got the buildings back and started asking: how do we repurpose these large spaces? Taylor Street is key—it’s the heart of Fisherman’s Wharf. That’s where the fishing industry relocated in the early 1900s, where the crab stands rose up, and where fishing happened right over the docks.

We want to reintroduce San Franciscans to the fishing industry, connecting Taylor Street to the Crab Wheel, the lagoon, and the views of the Golden Gate. Our investment is focused on bringing fishing into the public realm again and using smart leasing and property strategies to reimagine the area.

Alexis Madrigal: My understanding is you tried to lease Alioto’s, right? Took twenty different people through—restaurateurs and others—and nobody thought it could work as-is. That led to this broader plan?

Elaine Forbes: That’s right. The Wharf is still the most visited area in San Francisco. Smaller restaurants are viable, and many are open. But these large facilities require too much investment and don’t fit current tastes.

So we decided to focus on Taylor Street and especially Alioto’s, which we’d struggled to re-tenant the longest. Our team came up with a bold new strategy: demolish the building and create a beautiful public plaza.

Alexis Madrigal: We’ll talk more about that soon. We’re discussing the major renovation plans for San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf with Elaine Forbes of the Port of San Francisco, Sal Alioto, captain of the Golden Gate, and John King, author of Portal.

We want to hear from you. Fisherman’s Wharf holds a special place for many San Franciscans. Do you go there often, or never? Do you have a memory to share? What would you like to see change? Call us at 866-733-6786. Email forum@kqed.org. Find us on social media at KQED Forum or join the discussion on Discord.

Rick writes: I’d suggest the remodeling and renovation of Fisherman’s Wharf look the same but with stronger elements to withstand rising waters. And please, keep the Ferris wheel and the merry-go-round.

I’m Alexis Madrigal. Stay tuned for more on Fisherman’s Wharf right after the break.