This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Alexis Madrigal: Welcome to Forum. I’m Alexis Madrigal.

In the mornings, walking from BART across the Mission to the station, I often wonder about the lives of the people I pass doing drugs on Capp Street and in the alleyways of the neighborhood. Sure, they’ve made bad choices, and they impose costs on everybody else in the city. But how can it be that our region, our state, our country cannot help people — even after one million Americans have died of drug overdoses?

The failure is so profound that I think a lot of us have developed some ethical loopholes about people suffering from addiction. They’re lost to us. No treatment works. When someone goes down that road, it’s too late — etcetera, etcetera.

But one thing that Shoshana Walter’s book irrefutably shows is that when it comes to addiction treatment — when it comes to helping people who want help — we’re just failing people horribly, up and down the socioeconomic ladder, but especially those at the bottom. And even worse, a small number of people are profiting off exploiting the vulnerable.

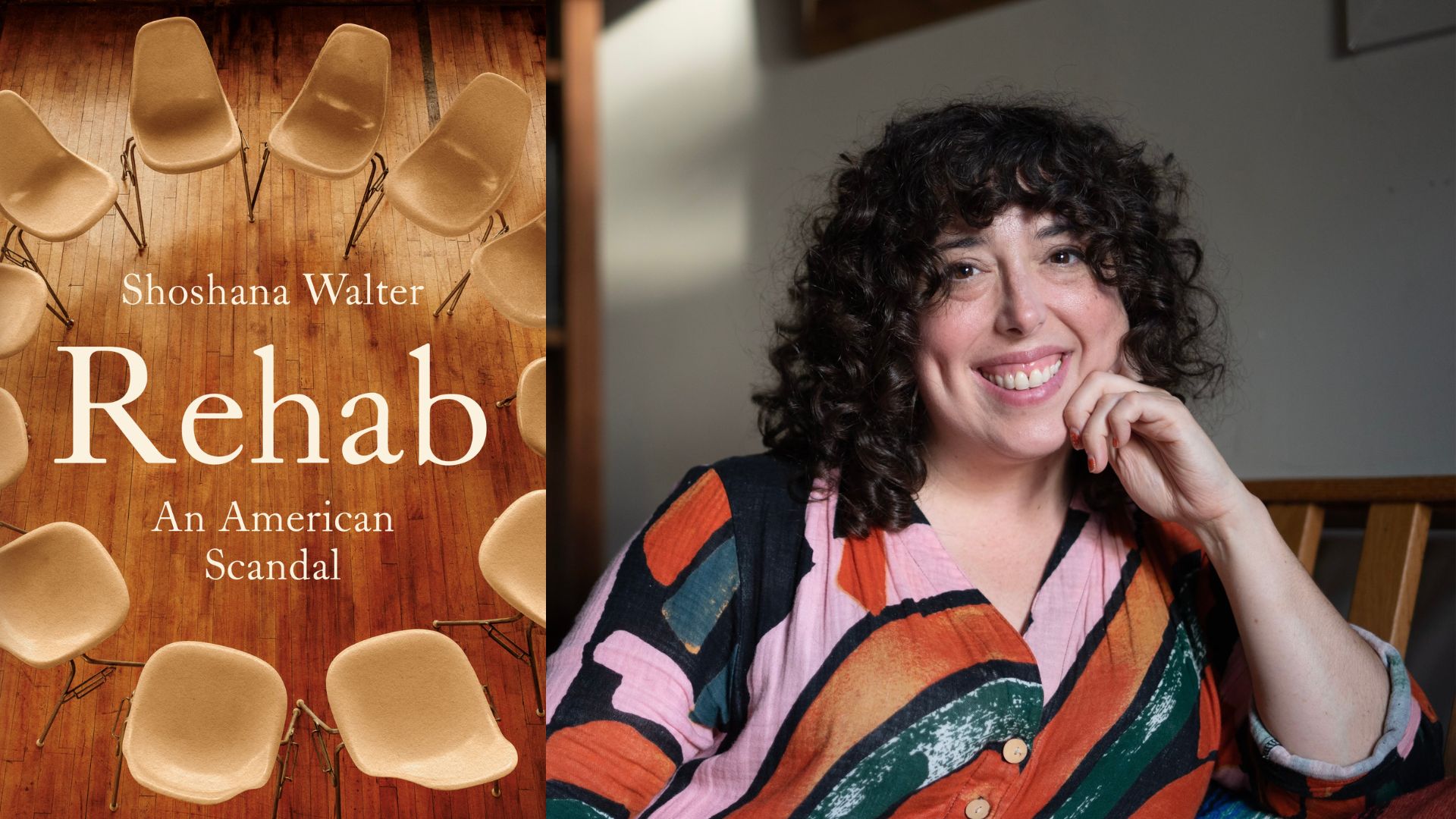

Here to share more about her book, Rehab: An American Scandal — and the reporting that informed it — we’re joined by Shoshana Walter, an investigative reporter with The Marshall Project. Welcome.

Shoshana Walter: Thanks so much for having me, Alexis.

Alexis Madrigal: So, the narrative I’ve had in my head about drug treatment in this country is that because the opioid epidemic hit a broader swath of American society than crack before it, our country decided to take a gentler, more treatment-based approach to drug addiction. But your book shows that we didn’t really do that. What went wrong?

Shoshana Walter: Yeah. I mean, exactly like you said — during the crack cocaine epidemic, our country’s approach to drug addiction was to criminalize and punish, and that led to mass incarceration of drug users, disproportionately Black and Brown Americans.

Then the opioid epidemic came around. It was more of a pain pill epidemic, mostly affecting white communities. And so there was this major transformation — a well-intended transformation — and a widespread acknowledgment that addiction is a disease, worthy of medical care and treatment.

Over the past twenty-five years, we’ve seen an enormous expansion of our treatment system — first, with the launch of Suboxone, the gold-standard addiction treatment medication, in 2002. And then with the Affordable Care Act, millions more Americans suddenly had coverage for addiction treatment.

But the system is really not working the way it was intended. A lot of the issues I lay out in the book have to do with people still being punished for their addictions — being sent to treatment programs that assign them to unpaid labor jobs working for some of the largest companies in America.

We have medication-assisted treatment like Suboxone that’s still hard for patients to access — many doctors don’t want to prescribe it. And then we have insurance-funded, 30-day inpatient programs that people come out of and then relapse. We now know that someone who completes a 30-day treatment program is actually more likely to overdose and die in the year after treatment than someone who doesn’t finish at all.

Alexis Madrigal: Which is — I mean — the exact opposite of what one might expect. Treatment is supposed to make you better, not worse.

Shoshana Walter: Right. Exactly. And even the best-intentioned treatment programs are often frustrated with this limitation imposed by insurance companies. Some treatment programs have taken advantage of it and made it part of their business model.

There was one treatment company owner I interviewed who admitted they were overmedicating patients to the point of impairment, contributing to overdose deaths in their own program. Even he was frustrated by the 30-day limit.

He called it a “cycler.” His company had staff call people who left their 30-day program to find out if they’d relapsed — and if they had, especially if they had good insurance, they’d reenroll them.

Alexis Madrigal: Bring them back.

Shoshana Walter: Exactly. It was just a cycle, in and out.

Alexis Madrigal: We’re going to go deeper into all these issues — Suboxone, different types of rehab centers, and why some of them don’t seem to work, or work in ways that seem cruel and unusual to me. But let’s talk about how you got into writing this book.

Eight years ago, you started looking into some of these treatment centers, and you found people working — as part of their drug treatment, for some reason — in a chicken processing facility? Tell us more about that.

Shoshana Walter: Yeah. I was a reporter at Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting at the time, and I stumbled across a program that a lot of drug courts and diversion courts in Oklahoma and Arkansas were using.

These were people who were supposed to be receiving addiction treatment instead of incarceration. It sounded great. But when I looked into it, I discovered the rehab program was founded by former poultry industry executives. Participants were sent to work unpaid at chicken processing plants, making products for KFC, Popeyes, Walmart, PetSmart, Rachael Ray Nutrish — products almost every American consumes.

That unpaid labor was predominantly their sole form of “treatment.”

Alexis Madrigal: And in your book, you trace some of this to a company called Cenikor, which one of the main characters in the book goes through. Where did they come from, and where did this idea — that putting people to work with minimal counseling — might work?

Shoshana Walter: Cenikor’s model came from a program called Synanon, founded in 1958 by a former oil salesman who struggled with alcoholism. He had tried AA and hated it because he felt people relapsed and lied in meetings. He didn’t want to let himself or others get away with that.

Alexis Madrigal: Tougher love was needed.

Shoshana Walter: Exactly. This became the precursor to rehab in the United States. It started as a community where people called each other out — yelling, confronting, holding each other accountable. Over time, it grew into recovery communities across the U.S., including in the Bay Area, where participants lived and worked, funding the program through unpaid jobs.

They also used what was later called “attack therapy” — or “the game” — circles where people verbally confronted each other.

Synanon gained popularity in the ’60s and ’70s, and its model was adopted by programs like the Cenikor Foundation. Eventually, Synanon became cult-like — the founder enriched himself, ordered vasectomies, mandated shaved heads, and forced marriages. It went off the rails, but it showed how a work-based model could become exploitative.

Alexis Madrigal: On the face of it, it seems a little crazy. But for some people, did it work? Did they become the biggest advocates — saying, “Look at me, it worked for me, it could work for you”?

Shoshana Walter: Yeah, I think so. There’s something compelling about stories of people entering a program and completely transforming their lives.

One former Synanon participant told my colleague at Reveal: “We brainwashed people — because their brains are dirty.” But many stayed in these programs for years, left, and relapsed. That’s a very common theme in U.S. treatment models — people do well while they’re in the program, but once they leave, it stops working.

Alexis Madrigal: Is there anything to the idea that once people are deeply addicted to drugs, there’s not much we can do?

Shoshana Walter: No — I think there’s so much we can do to help people recover. Many people recover over time, even without treatment. People age, grow, and naturally change.

The problem with our drug policies is that the longer someone is in addiction, the more marginalized they become, and the harder it is to recover — because they’re lacking the things needed for long-term recovery: housing, jobs, financial resources, social support, transportation.

Without these, sustaining recovery is much harder. And there are other barriers I detail in the book.

Alexis Madrigal: You call it “recovery capital,” right?

Shoshana Walter: Yes. Researchers told me how important recovery capital is — the resources that help people envision and achieve change: community, housing, transportation, food, financial security. Without these, relapse is almost inevitable after treatment.

Alexis Madrigal: We’re talking about America’s drug treatment system and the rehab and addiction recovery industry. We’re joined by Shoshana Walter, author of Rehab: An American Scandal. She’s now an investigative reporter for The Marshall Project.

We want to hear from you — have you had experiences with the rehab industry as a patient or a provider? What was your experience? Give us a call at 866-733-6786. You can also email us at forum@kqed.org. We’re on social media @kqedforum.

I’m Alexis Madrigal. We’ll be back with more right after the break.