Hurt's personal story is flanked throughout the film by commentary from a range of historians, scholars, soul food chefs, doctors, and everyday folk who illuminate the cultural complexities in the African American relationship to food. “Soul food is a repository for our history,” says one.

Discussions about food in the historical context of slavery and the Jim Crow era help to illuminate the subject. Slavery was an economic institution and slaves had to be fed enough to survive the long voyage. Once here, some were expected to grow their own food and others hunted and fished like they did back in Africa. Also, female slaves were doing the cooking for the people in the big house and taking care of the children. “The hand of the African in the pot transformed Southern cooking,” comments one food expert. “Survival food for slaves became delicacies.”

“Slaves did what they needed to do to survive and make it through harsh times," explains Hurt. "Then that way of cooking got passed down from generation to generation. And today there is a reluctance to let go of the vestiges of the way of life of our forefathers and foremothers, even though things have changed: foods are now processed and full of chemicals and we’re not as active as previous generations.”

Fried chicken. Photo: Shawn Escoffery

Hurt’s mother describes the reasons she always prepared box lunches for the family to eat on their annual drives from their home in Long Island to Georgia. Because of Jim Crow laws, Black people could not be sure of finding hotels or restaurants that would serve them during road trips and so routinely brought hearty lunches of fried chicken and sides to keep them satisfied until they reached their destination.

More recent history shows that there has been a movement for healthy food awareness in African American culture for many years. “The best moments of the black freedom struggle, was with organizations like the Black Panthers," comments a food historian. "They understood the relationship of developing a Black nation and the necessity of developing a healthy diet.”

Others interviewed in the film, however, are still very attached to Soul Food (the term was first coined in the '60s) and find creative rationalizations to keep eating it, such as, “Eve was made out of Adam’s rib, so ribs must be good.”

Ribs, cabbage, rice, and potato salad on the side. Photo: Shawn Escoffery

A poignant scene has Hurt stopping by some tailgating partiers at Mississippi's Jackson State University. The affable group of guys shows Hurt their “Junk Pot”--a huge stock pot filled with corn, pigs ears, pig feet and “everything else that’s not good for you.” With classic Southern hospitality, they invite him to have a sample. Hurt, who has stopped eating pork, doesn’t wish to offend these gentlemen, and so delicately extracts a small cob of corn to taste. This ploy does not escape the partiers who insist he take some meat. Hurt finally does sample a dripping turkey neck and reluctantly admits how delicious it is.

Educating any cultural group about the unhealthiness of treasured comfort food is a challenge because the concept of “comfort” connects us to foods that mom or grandma made and even fed us with her own hands. This primal, sensory gratification exists on an emotional, pre-verbal level, which does not speak the rational language of blood pressure screenings. In 2010, Saul’s Deli in Berkeley engaged in a similar debate and dialogue regarding nostalgia for “real” deli food (e.g. mile-high pastrami sandwiches) vs. the wisdom of sustainability.

As a woman in Soul Food Junkies put it simply, “It’s comfort food, you eat it and it makes you feel better.”

Yet, in the face of staggering statistics of diabetes, high blood pressure, and certain types of cancer rampant the African American community, food experts in the film comment on the urgent need to increase awareness and make changes now, before it’s too late.

“If you want to wipe out an entire generation of people and engage in a 21st century genocide, all you have to do is to continue doing what we’re doing and deprive people of access to healthy food.”

Food justice, food deserts, lack of access to healthy food and the proliferation of fast food all play a critical role in this discussion. As one food scholar puts it, “In America, there is a class-based apartheid in the food system.” Hurt realizes that traditions, especially those that speak to times of family togetherness and comfort, are resistant to change. Instead of quitting classic soul food dishes cold turkey, some cooks in the film choose to tweak traditional recipes, like making oven-baked, skinless chicken instead of deep-fried. “We have to make it a part of popular culture. We have the power to change and if we don’t, we’ll be sick and die.”

Soul Food Junkies makes clear that hope for the future rests with the children. One of the last shots in the film is a group of African American elementary school children from St. Philips Academy in Newark, New Jersey. The school’s “family-style lunch program, rooftop garden, teaching kitchen and science lab encourage an understanding of sustainability from seed to table.” We see the children yell happily, “Vegetables are Soul Food!”

Hurt’s last film, Hip-Hop: Beyond Beats and Rhymes, an award-winning documentary, was also selected for Independent Lens. It examines "masculinity and manhood in rap and hip-hop, where creative genius collides with misogyny, violence and homophobia, exposing the complex intersections of culture and commerce.”

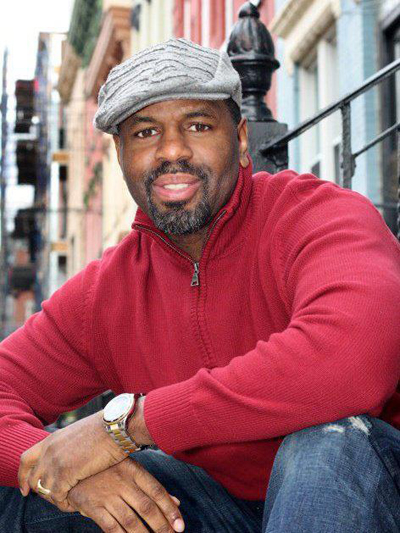

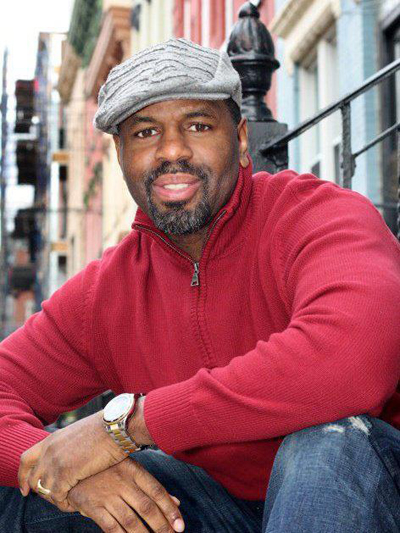

Filmmaker Byron Hurt. Photo: Rebecca Bfresh McDonald

INTERVIEW WITH BYRON HURT

BAB briefly interviewed Byron Hurt by phone, while he was attending the American Black Film Festival in Miami where Soul Food Junkies won Best Documentary.

First you took on hip-hop and now soul food, are you trying to change African American culture?

I’d say I’m trying to make the culture better and stronger and challenge people to think critically about their culture.

What is your goal?

To challenge and inform people’s thinking. I‘m trying to create tools that inspire and educate so there can be a transformation and evolution to greater self-awareness. I used myself and my family as examples of what happens when you decide to change your diet and when you don’t. There might be many people out there who have been wanting to change, but need a nudge or some inspiration. Or maybe they want to help a family member or co-worker to change.

Isn’t comfort food hard to be rational about?

It is a very hard thing. I may have underestimated how hard it is. I saw with my own eyes that despite all the health challenges, it was still difficult for my father to change the way he ate.

What inspired you personally to change your diet?

It was my sister who set the first example in my family when she changed to a plant-based diet and I saw how healthy she looked. I had started to gain weight in my late 20s and early 30s. I realized that not being involved in athletics anymore [Hurt was a football quarterback in college] I couldn’t continue to eat and eat and eat the same way I had been. So I changed my diet and lost weight and felt better. My mom was more open than my father. She was a nurturer. She changed the way she cooked because she wanted to make us happy.

LOCAL RESPONSE FROM PANEL

Closer to home, the panel of food activists after the Oakland screening of Soul Food Junkies said much to stir up the crowd.

Aekta Shah of I-SEEED at Harvard. Photo courtesy of Aekta Shah

Aekta Shah, who works with I-SEEED -- The Institute for Sustainable Economic, Educational, and Environmental Design, described two exciting projects. In 2011, about 30 high school students from Oakland, Richmond and San Leandro hit the streets to check out the statistics from the Alameda County Department of Public Health report that there were about 100 grocery stores in Oakland. First the students had to come up with their own definition of “grocery store.” Does that mean it carries fresh produce? Skim, 1% and 2% milk, instead of just whole milk? A certain ratio of healthy to junk food? Affordable choices? Then they formed teams and walked through stores in their own neighborhoods, documenting what they found, recording audio testimonials, taking photos of the shelves. The students uploaded their data and photos onto a Google-map-like interface and ultimately shared their findings with representatives of Alameda County Public Health Department to begin a dialogue around community-based solutions to these issues of food access. In a related follow up, I-SEEED is in conversation with California FreshWorks around partnering to help finance owners of neighborhood liquor stores to transform their stores into grocery stores stocking healthy food.

Eco-chef and author Bryant Terry. Photo: Jennifer Martin

Eco-chef, food activist and author of several vegan soul food cookbooks, Bryant Terry spoke eloquently both as a commenter in Hurt’s film as well as a panelist. The problem, says Terry, is not soul food per se, but the industrialization of our food supply. The industrial food complex spends billions of dollars trying to convince people to eat food that’s the worst for them: highest in fat and sugar.

Terry, who moved to Oakland in 2006 for its natural beauty and calls the Bay Area “my spiritual home,” points out that, “Eating close to the land is not a new invention, African Americas have been green, with aunties and grandmothers who grew their own food for generations. You can still be a “brother of color and eat healthy. You don’t have to be a crunchy-granola, Birkenstock-wearing hippie.”