Why have animals on a farm? Well, as one of the owners of Full Belly Farm pointed out, a productive, diversely-planted organic farm produces a lot of surplus food. Restaurants, retailers, CSA and farmers' market customers all want the good stuff. They'll pay for it, but it has to look and taste the best. And if you're not bathing your produce in pesticides to keep it the boring, munching, scarring bugs at bay, well, you're going to end up culling a whole lot of not-so-pretty, overripe or undersized stuff along the way.

Some of it feeds your family and your workers. Some of it can feed your compost. But if you want to turn oversize zucchini and beat-up tomatoes into usable, high-quality protein (not to mention plenty of fertilizer), well, nothing beats feeding it to pigs, goats, or chickens.

Backyard goats and chickens enjoying some sweet and crunchy discards from Star Route Farm

It's all part of the closed-loop system advocated by Rudolf Steiner, the Austrian polymath who mixed biology and soil science with folk wisdom and time-tested peasant farming practices, codifying it into what we now call biodynamics. Stripped of its more arcane spiritual elements, it's more or less the same down-to-earth, interconnected system advocated by Joel Salatin, the nattily dressed farmer/author of Virginia's Polyface Farm, who gave an impassioned speech last month in Point Reyes Station. Drawing from his latest book, The Sheer Ecstasy of Being a Lunatic Farmer, Salatin turned the hay-lined Toby's Feed Barn into a tent revival for smart pasturing practices and mixed-use farms. Real pork, he insisted, wasn't a "white meat;" instead, if the pig's been raised right, rooting around, living out its full pig-attude, its meat should be iron-rich and consequently rosy pink.

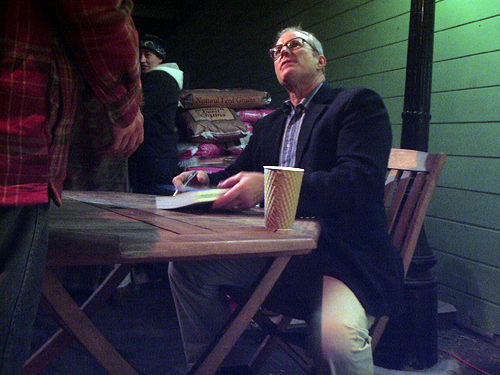

Joel Salatin. Photo by Stephane von Stephane

Even wineries are getting in on the act: at Robert Sinskey, in Napa, part of the vineyards' biodynamic practice involves grazing down the weeds with sweet-faced Romney sheep, whose wool is sold alongside the wine in the tasting room.

But, as much as we might hope to be going back to a more natural practice with grass-fed meat and pastured eggs, few consumers are ready to think of steak and omelets as exclusively seasonal products, dictated by water, daylight, and temperatures just as much as asparagus or raspberries. If you have backyard chickens, you know that laying slows down dramatically as the days get shorter. Grass-fed cows have to be managed according to the ecosystems of their particular pastures.

Rearing animals on grass takes time, and as talk with numerous small farmers and ranchers at the conference proved, no one small farm or ranch can provide a year-round supply of freshly slaughtered meat. The answer? Co-ops and partnerships. As the workshop "Are CSAs Sustainable?" proved, a single farm limited by acreage, climate, and resources can't always produce enough variety to keep customers coming back for a box year-round. Your cool, moist, ocean-fogged farm might produce spectacular greens and kales—but what happens in July, when "greens fatigue" sets in and your members are longing for peaches and tomatoes? You can preach the virtues of chard; scrape up another loan, lease another parcel of land and increase your payroll; or partner with an inland neighbor already dripping in stone fruit and create a box that shares the wealth.

Niman Ranch does this on a large scale; Marin Sun Farms, Straus Family Creamery, and North Coast Meats on a smaller one. Partnering with other ranches helps produce a steady supply, while selling meat through a CSA, like the one described by Tyler Dawley of Barbarosa Ranchers in Red Bluff, insures not only a pre-sold market for the animals, but a chance to familiarize customers with cuts beyond the usual chops and tenderloins.

Cooperatives can also help with the biggest snag in the local-meat supply chain: getting access to a small-scale slaughterhouse, then finding a way through governmental wrapping and packing regulations scaled for the likes of Tyson Foods.

As State Director Dr. Glenda Humiston of USDA Rural Development pointed out, one of the top requests her office gets from rural communities (right after broadband) is access to small-scale slaughterhouses, particularly mobile ones that can move from community to community. Throughout the workshops, farmers with pigs, goats, sheep, and cattle on their land got up to beg for solutions, giving details of sudden shut-downs at nearby slaughterhouses (some affiliated with local ag-training universities) or wrapping/packing facilities.

No one, even the most carnivorous among us, likes to think too hard about how their main course went from animal to ingredient. But with meat moving out of the supermarket and into the farmers' market, thoughtful consumers have more and more chances to find out how their dinner lived, and to put their food dollars towards supporting land-healthy, humane practices.