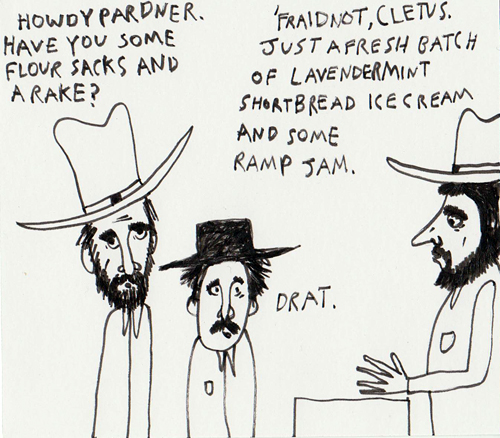

When I think of general stores, I imagine rough-hewn outposts in dusty mining towns swirling out of sepia-hued cowboy flicks -- places where grumbling codgers hawk dry goods, tools, soap, guns, and clothes to a small population of frontier folk. I'm a scholar of spaghetti (and spaghetti westerns), not by any stretch an expert on expressions of culture and community in isolated towns on the American Western front during the latter portion of the 19th century. Still, I imagine that those stores were places where people went to get the things they could not grow, raise, or make for themselves. And they were dependent on them, not just because they ferried along much-needed goods from faraway places, but because they acted as centers of community activity. Residents of a small town might go to the general store to buy flour and end up seeing each other, sharing stories, and bonding. By my amateurish reckoning, it's a pretty good example of community coming together naturally, face-to-face, materializing in a place where needs are met, back when needs couldn't be met anonymously via online shopping or a trip to a big-box retailer.

This is what I was thinking when, last Thursday, I read a San Francisco Chronicle food section story about a "general store" popping up, not in some grim mud-slicked alley of Deadwood, but in Oakland, California -- urban epicenter for community-conscious adventures in sustainable food and agriculture. Every few weeks, a revolving cast of Chez Panisse and Eccolo vets set up shop and sell sausages, heat-and-serve entrees, fresh pastas, frozen pizza dough, jams, breads, and ice creams -- high-end convenience foods to stock fridges and freezers for quick dinners and easy lunches. In the piece, Chronicle writer Carol Ness draws parallels between this pop-up and the larger trend of which it is emblematic:

"The store is part of the new phenomenon of temporary eateries, farm stands and even one "underground market" that spring up here and there around the Bay Area, sometimes regularly in the same location, sometimes not."

Simultaneously, however, Ness makes an effort to set this new enterprise apart:

". . .[S]o far the Pop-Up General Store is one of a kind because its wares carry an exceptional pedigree: They're made with pristine ingredients -- Becker Lane pork, Soul Food Farm eggs, Riverdog produce -- by a dozen or so Bay Area chefs, almost all of whom cook or have cooked at Chez Panisse."

That pedigree, of course, comes at a price the average Oakland resident can't pay. As portrayed, the general store suggests a movable mini-Ferry Building, a stroller-clogged social scene for self-described "foodies" swooning over chicken confit and bags of freezer-ready heritage pork gyoza, not a place to do serious shopping. That doesn't necessarily bother me. Elite eating (and shopping) is an articulation of values. I rarely buy shoes, and cheerfully wear the few I own until they fall apart and literally flap off my feet -- all because I'm cheap and don't see the point in having more than a few pairs at a time. I won't, however, buy steaks at Foods Co. By calling their enterprise a "general store" though, founders Christopher Lee and Samin Nosrit (well-known East Bay chefs I first encountered reading through Novella Carpenter's Farm City) are actively trying to evoke the sort of life-sustaining community-generating apparatus that came to my mind the moment I saw Ness's headline -- all while selling boudin blanc for $14 a pound. While such a project might draw attention to certain sections of the community -- producers, chefs, growers -- and bring together others -- hungry food writers, people with money -- the vibe -- however delicious -- doesn't quite jive with the handle.