I visited the old Bonny Doon within four months of moving to California. The year was 2002. Tickled at the idea of crashing a tasting room, my then-roommate and I motored through the mountains in a borrowed car, the Doon our destination solely on the strength of a few cheap bottles we'd downed. It was a few days before Halloween, and as we sauntered into the building (It's been long enough that I scarcely remember the exterior), we realized we were not the carousing pranksters, but instead the straight men: Every member of the Bonny Doon tasting room staff was dressed in a costume. I saw a bear, a clown, and a few ghosts in sheets just begging for cardinal-colored stains. A young woman -- a witch -- asked us what we wanted, and we had no idea. We wound up taking home a few selections -- including a lovely Framboise I shipped off to my mother.

I visited the old Bonny Doon within four months of moving to California. The year was 2002. Tickled at the idea of crashing a tasting room, my then-roommate and I motored through the mountains in a borrowed car, the Doon our destination solely on the strength of a few cheap bottles we'd downed. It was a few days before Halloween, and as we sauntered into the building (It's been long enough that I scarcely remember the exterior), we realized we were not the carousing pranksters, but instead the straight men: Every member of the Bonny Doon tasting room staff was dressed in a costume. I saw a bear, a clown, and a few ghosts in sheets just begging for cardinal-colored stains. A young woman -- a witch -- asked us what we wanted, and we had no idea. We wound up taking home a few selections -- including a lovely Framboise I shipped off to my mother.

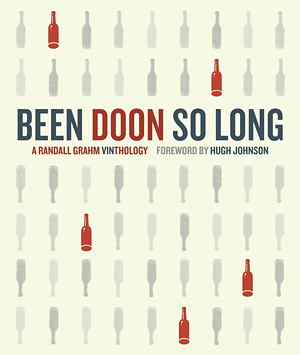

Since then, Bonny Doon has moved to Santa Cruz, sold a few of its bank-breaking mainstream labels, and most recently, shifted its focus from winsome, cleverly-marketed table fare to quirky, more rarefied wines made using organically grown grapes (invariably oddball Italian varietals) and biodynamic methods. At the same time, owner Randall Grahm has seen his profile grow, not because of the bottles he's produced, but as a result of his well-publicized literary efforts -- from newsletter manifestos to provocative cartoon ads in widely-read wine magazines and crushing commentaries cloaked in clever wine-y homages to canonical novels and poems. That career, a supple, sturdy vine shooting off his winemaking business's freshly trimmed root, culminated -- at least so far -- in last year's "vinthology" Been Doon So Long, a self-curated collection published by the University of California Press. The title, I assume, is a play on Richard Farina's 1966 novel Been Down So Long, It Looks Like Up to Me, the book Farina was promoting on the very night he died in a motorcycle accident near Monterey.

After my short strange trip to the old tasting room back in 2002, I followed Bonny Doon in the news, and even made a point of buying the company's wines when I could. Already thoroughly charmed by his labels frequently featuring wild, splotched, and puckered caricatures drawn by Ralph Steadman, a favorite artist, I was also taken with Grahm's funny essays, and enamored of the prospect of supporting a good writer by drinking his wine. A few weeks ago, Been Doon So Long won a James Beard Award, and I figured the time had come to reacquaint myself with Grahm's body of work.

The body is the size of a biology textbook, which is probably appropriate considering the subject matter. At the same time, essays so dense, so rife with potentially unfamiliar terms and allusions that require quick references, suit a more portable package, something to be tucked into a jacket pocket, read in installments on public transportation, and marked with folded corners, underlines, and scribbled notes. Instead, the book is huge, heavy, and handsome. It looks good in a case, or on a coffee-table, but actually reading it requires physical effort. It's a little cumbersome to hold up while lying prone in bed. If you fall asleep reading it, you might break your nose, so don't try doing so after reaching the bottom of a bottle of syrah. Instead, you need a strong, straight-backed chair, a cup of coffee, and the warm morning light. Some oenology acumen and a solid background in Western literature doesn't hurt either. I am equipped with the latter, but -- as someone quite comfortable picking out something nice to drink with dinner, yet woefully ignorant of winemaking practices and quite hazy on the cultural worlds and myriad personalities, both human and grape, surrounding them -- plenty of Grahm's jokes (and a few of his key points) swirl above my head like clouds of must. With respect to some of it, like a high school junior trying to make sense of Ulysses, for the first time, perhaps a year or two too soon, I'm happy getting the gist.

Aside from introducing the reader (who is probably already familiar) to Grahm's general vibe, the book takes two distinct tacks. The first -- palpable in his gleeful parodies -- is the wine world equivalent of a dis record, and a fairly hilarious one at that -- with upstanding luminaries like Robert "Moldavi," disagreeable trends such as "merlotmania," and, of course, the critic Robert Parker looking flimsier than 2010-era 50 Cent. The insults are often no less opaque than those hurled by a derisive rapper, and the effect is equally delicious, though with salvos of double entendre, puns, copious footnotes, and a constant barrage of drunken word-play (For example, and there are thousands, the wine "dick" in "Spenser's Last Case" wields a Gattinara, not a gat), considerably cuter. The formula is consistent and agreeable: Grahm apes the style of a famous author -- Thomas Puncheon, James Juice, or J.D. Salignac, perhaps -- and unloads a lecture cloaked in a madcap, script-flipping of themes in a well-known work by the particular author -- say, "B," "Cheninagin's Wake," or "A Perfect Day for Barberafish." Most of these are as pleasant and drinkable as a $12 bottle of Gruner, if a bit more demanding, and somewhat heavier on the palate. The song and poem parodies that follow are less successful; they seem watered-down, like Grandma's pink zin.