Most reviews of Gristle will start with an assessment of Moby, the fantastically irritating middle-aged multi-platinum electronic musician-turned-food policy expert who edited the book. Based on what I know of Moby, I do not like him. It wouldn't be fair to hate him. Hating is a tough thing to do, even when you really know someone well enough to feel okay about doing it. While, for a long time, Moby barely registered a chirp on my pop culture radar, he first became the subject of my considerable distaste in 1999, when his mega-smash album Play came out, saturating radio station playlists, television commercials, and department store dressing rooms with "soulful" Alan Lomax-recorded blues samples wrapped in pulsing techno. The songs were inescapable and horrible. Much to my dismay, they chased me everywhere I went. More recently, in late March, weeks before this book arrived in my mailbox, I thought of Moby again when the New York Times published a Sunday Routine feature about him. Every section reads as if the author (Moby, in his first-person voice, presumably as recorded and edited by writer Lizette Alvarez) cannot help but be astounded by his own charm and cleverness. He names his favorite kind of organic tea, brags about his wretched-sounding pancakes, revels in online Scrabble victories, rattles off a vile but fiercely healthy smoothie recipe, and (on account of Calvinist ancestors) admits to a few "guilty" pleasures -- including that leviathan of vice, "mass market fiction." A friend linked to the article on Facebook, adding a highly derisive caption. A day later, a mutual friend commented on the post, sharing a shameful nugget of hearsay from yet another friend who apparently knows Moby quite well -- well enough to text with him, at least. According to this undoubtedly suspect source, when Moby texts, he dutifully concludes each message with a jaunty sign-off: "This is Moby, on the text."

Most reviews of Gristle will start with an assessment of Moby, the fantastically irritating middle-aged multi-platinum electronic musician-turned-food policy expert who edited the book. Based on what I know of Moby, I do not like him. It wouldn't be fair to hate him. Hating is a tough thing to do, even when you really know someone well enough to feel okay about doing it. While, for a long time, Moby barely registered a chirp on my pop culture radar, he first became the subject of my considerable distaste in 1999, when his mega-smash album Play came out, saturating radio station playlists, television commercials, and department store dressing rooms with "soulful" Alan Lomax-recorded blues samples wrapped in pulsing techno. The songs were inescapable and horrible. Much to my dismay, they chased me everywhere I went. More recently, in late March, weeks before this book arrived in my mailbox, I thought of Moby again when the New York Times published a Sunday Routine feature about him. Every section reads as if the author (Moby, in his first-person voice, presumably as recorded and edited by writer Lizette Alvarez) cannot help but be astounded by his own charm and cleverness. He names his favorite kind of organic tea, brags about his wretched-sounding pancakes, revels in online Scrabble victories, rattles off a vile but fiercely healthy smoothie recipe, and (on account of Calvinist ancestors) admits to a few "guilty" pleasures -- including that leviathan of vice, "mass market fiction." A friend linked to the article on Facebook, adding a highly derisive caption. A day later, a mutual friend commented on the post, sharing a shameful nugget of hearsay from yet another friend who apparently knows Moby quite well -- well enough to text with him, at least. According to this undoubtedly suspect source, when Moby texts, he dutifully concludes each message with a jaunty sign-off: "This is Moby, on the text."

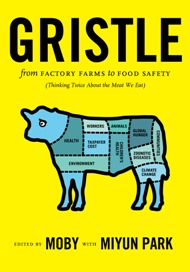

While Gristle's editor might come across as a smug self-righteous cartoon, an easy target given the trappings he's prone to wearing, the message he, co-editor Miyun Park, and the host of noble experts they've gathered are pushing is real and worthy of very serious discussion. Simply put, this book -- a featherweight at 144 pages -- has forced me to re-contemplate the advantages of vegetarianism in the face of a corporation-clogged taxpayer-funded mainstream meat industry dedicated to processing artificially cheap, unhealthy, and potentially dangerous animal protein products for mass consumption, with a startling disregard for its underpaid workers and the environment.

In Gristle, each contributor handles a brief chapter with a one word title focusing on a single negative aspect of factory farming's effect on people, animals, and the world -- an issue to house arguments supported, in turn, by facts. It's a tidy assemblage of frill-free prose and grim, gray-scale visual aids. There's a uniformity to the writing and presentation uncommon to a collection of such far-flung perspectives, but the diversity nips any argument that Moby's cast of contributors are all cut from the same animal rights activist cloth.

There's Brendan Brazier, Canadian Ironman triathlon competitor, weighing in on health. asserting that, "leaving farm animals out of your diet is a simple decision with life-long benefits." Whole Foods honcho and dedicated libertarian John Mackey talks taxes, revealing that Americans currently spend 8% of their incomes on food, whereas, one hundred years ago, they spent over five times as much -- a change brought about, in part, by government subsidies that distort markets "tremendously." Christine Chavez and Julie Chavez Rodriguez, human rights activists and granddaughters of Cesar Chavez, write about the abysmal working conditions in factory farms. Paul and Phyllis Willis, the manager of Niman Ranch Pork Company and a community activist respectively, discuss how factory farms tear up communities: In just two decades, Iowa has seen an 84% decrease in the number of farms raising pigs, yet almost five times as many pigs. That means bigger farms, and less farmers. Lauren Bush, C.E.O. and co-founder of FEED as well as the niece of George W., focuses on the environment, and Diet for a Small Planet author Frances Moore Lappe and her daughter Anne address global warming, offering up a specific morsel I actually remember stewing over in my youth: 16 pounds of grain and soy are required to raise one pound of steak.

I have written before about my own experiment with vegetarianism. I never ate much meat as a kid, largely because my parents didn't. I stopped altogether when I was 13, in 1993. I tasted fish again in 2001, and poultry a few years later. Before long, I was a full-bore bone-gnawing omnivore, even more adventurous and meat-centric once I began writing frequently about food for amusement and income. Reading Gristle sent me back to a time I often struggle to remember -- the moment I decided to stop eating meat -- and about halfway through the book, I wondered why I had. There was a time not long ago when I saw the meatless phase of my young life largely as a drawn-out gesture of gentle rebellion against my cultural surroundings, a politicized substitute for dying my hair green. I was only vocal and remotely militant about vegetarianism for a few years, and yet I remained a vegetarian for many more. Did I stick to my diet out of habit? Was I trapped by a desire to maintain consistency? Making sense of the flights of logic generated by my 16-year-old mind always requires major effort, but in this matter, I was probably never so stupid. Meat -- as most of America knows it, and has known it for decades -- might not be murder, but it is a huge unholy mess.