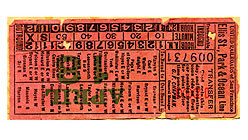

What happens when items meant to be used briefly — like travel guides, ticket stubs, and menus — are kept instead of discarded? What happens when this ephemera is collected over 170 years, growing steadily until it spans a sweeping range of interests, businesses, social concerns, and events of historical import? Archives and libraries committed to preserving such material are faced with a dilemma. Unlike your average hardcover, a personalized ticket booklet from the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exhibition (San Francisco’s first World’s Fair) can’t be checked out to patrons. Ideally, historical ephemera should be readily accessible, but without proper records and a way of searching them, the public will never find a gateway into such a collection.

To remedy this situation, four San Francisco institutions — the California Historical Society, the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society, the San Francisco Public Library, and the Society of California Pioneers — launched the California Ephemera Project. With a 2008 grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources titled “Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives,” the partners began a two-year marathon of sorting, sifting, and identifying their respective ephemera. The project is not the fully-scanned repository we’ve come to expect from the internet (see Google Books), but the collections’ folder headings are now searchable via the Online Archive of California, providing general information on the items they contain.

Armed with a list of tantalizing categories, I stopped by the California Historical Society to meet interim executive director Mary Morganti, the Ephemera Project’s principal investigator, and Wendy Welker, the Project’s manager and a CHS archivist. They met me with a full cart of gray archival boxes, each one containing folder after folder of postcards, booklets, coupons, and more. At the start of sorting through the CHS archives in April 2009, Welker wrote on the project blog: “This processing work has definitely highlighted the inconsistencies (including some very unorthodox alphabetizing) and general wackiness (Shaun Cassidy bio folder containing one clipping) of uncataloged ephemera collections.” Even Morganti and Welker were unsure of how many boxes of material staff and volunteers sorted. Their best guess? “Hundreds.”

Armed with a list of tantalizing categories, I stopped by the California Historical Society to meet interim executive director Mary Morganti, the Ephemera Project’s principal investigator, and Wendy Welker, the Project’s manager and a CHS archivist. They met me with a full cart of gray archival boxes, each one containing folder after folder of postcards, booklets, coupons, and more. At the start of sorting through the CHS archives in April 2009, Welker wrote on the project blog: “This processing work has definitely highlighted the inconsistencies (including some very unorthodox alphabetizing) and general wackiness (Shaun Cassidy bio folder containing one clipping) of uncataloged ephemera collections.” Even Morganti and Welker were unsure of how many boxes of material staff and volunteers sorted. Their best guess? “Hundreds.”

The results of all that hard work are worth seeing firsthand. Highlights from my visit included a witty dance card from an 1872 Sadie Hawkins-style soiree. Rules for the night insist: “Ladies will endeavor to avoid leaving their partners standing alone in the centre of the room, on account of the awkwardness of the situation.” Another favorite informed me of a movement I never knew existed. It was a small paper pamphlet from the Anti Digit Dialing League, published in 1962. Arguing against the transfer from phone numbers such as MArket 6-5000 to our current ten-digit system, the text ominously declares: “beware creeping numeralism.” In one box, I glimpsed a folder titled “Bona Fide Thespian Leprechaun Brotherhood.” Shockingly, there is absolutely no information on the members or activities of the Bona Fide Thespian Leprechaun Brotherhood anywhere online, emphasizing the importance of this file’s very existence.

Historians (professional and amateur), art students, family genealogy researchers, and novelists all make regular use of the CHS collection — aided greatly by its online presence. While the moods and interests of a time are so often sought in photographs, ephemera provides a mixture of personal and anonymous information that helps fill the gaps in, or open entirely new doors to, our understanding of history. And though the California Ephemera Project focuses on the past, additions to the collections are ongoing at all four participating institutions. Welker admitted to scooping up a bit of confetti in the aftermath of the Giants’ World Series victory parade. She brought it back to the California Historical Society as a welcome addition to the collection.

Historians (professional and amateur), art students, family genealogy researchers, and novelists all make regular use of the CHS collection — aided greatly by its online presence. While the moods and interests of a time are so often sought in photographs, ephemera provides a mixture of personal and anonymous information that helps fill the gaps in, or open entirely new doors to, our understanding of history. And though the California Ephemera Project focuses on the past, additions to the collections are ongoing at all four participating institutions. Welker admitted to scooping up a bit of confetti in the aftermath of the Giants’ World Series victory parade. She brought it back to the California Historical Society as a welcome addition to the collection.