Trina Michelle Robinson is trying to talk to ghosts. For 10 years, the San Francisco-based artist has been on a journey to uncover and share the stories of her ancestors and the legacies of Black migration. She hasn’t always succeeded – and that’s exactly what makes her work powerful.

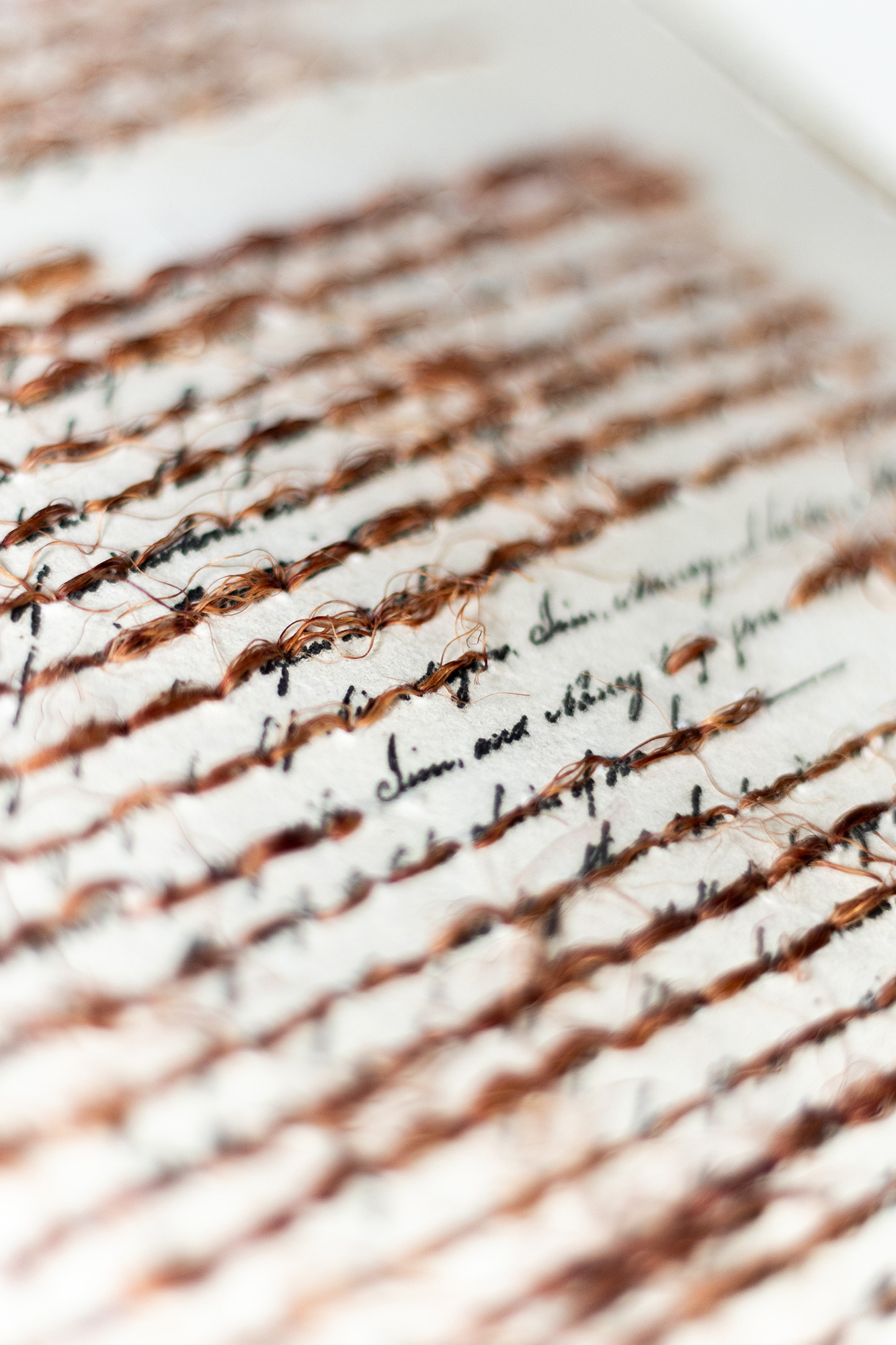

Robinson’s two-venue exhibition Open Your Eyes to Water, on view through May 16 at 500 Capp Street in the Mission, and Root Division, South of Market, contains work from the past decade, spanning multiple mediums, continents and histories. All of Robinson’s work begins with archival research, mining the records of her ancestors’ lives in Kentucky, Ohio and California. The results include video and installation as a form of embodied history, photography and printmaking as a way of engaging directly with the archive.

At 500 Capp Street, former home of conceptual artist David Ireland (1930-2009), Robinson has staged three installations. Encoded (2022), a three-channel video piece in the house’s garage, opens with a long shot of the Ohio River before following Robinson’s own travels to Senegal, seeking vestiges of what her ancestors might have experienced. The film ends on the underwater memorial for the Henrietta Marie, a British slave ship that sank off the Florida Straits in 1700, with Robinson’s sparse voiceover documenting the trip.

In 500 Capp Street’s archive room, Robinson’s own archival materials showcase the historiography essential to her practice while noting a glaring omission from Ireland’s.

“Marginalized voices weren’t always celebrated in certain parts of David’s life,” Robinson tells KQED. “If you look at his book collection, especially in relation to Africa, many are about people going to Africa for adventure. I’m welcoming the narrative David left out, fully focused on the Black experience.”