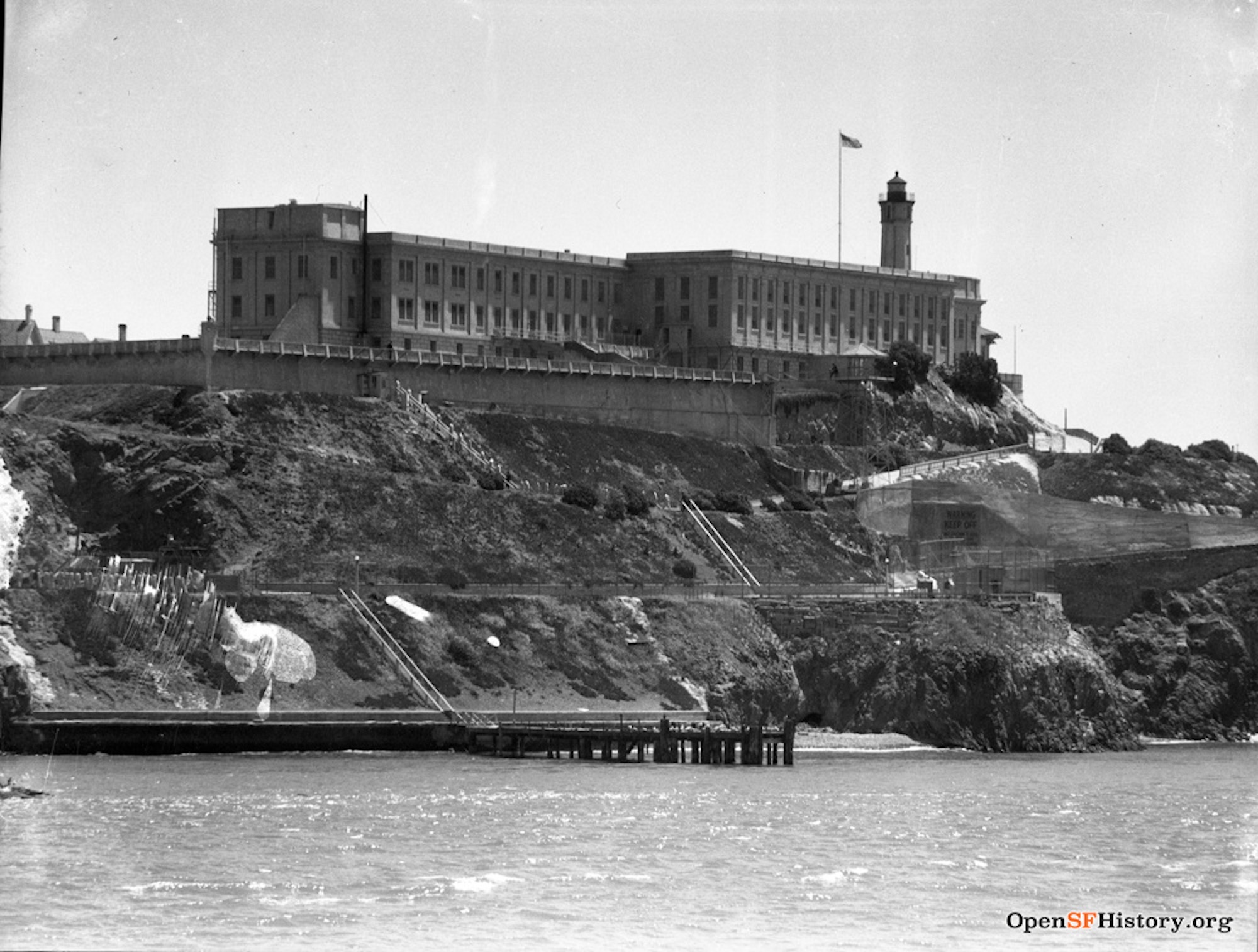

As all good Bay Area history nerds know, Alcatraz Prison closed in 1963, less than a year after Frank Morris and John and Clarence Anglin escaped from the island, never to be seen again. What is less well known is that there were serious calls to shut down the prison all the way back in 1939, just five years after it opened. That was after a different escape attempt put a spotlight on the failures and flaws of The Rock, and prompted debate all the way to Washington, D.C.

How a Little-Known Escape From Alcatraz Almost Closed the Prison in 1939

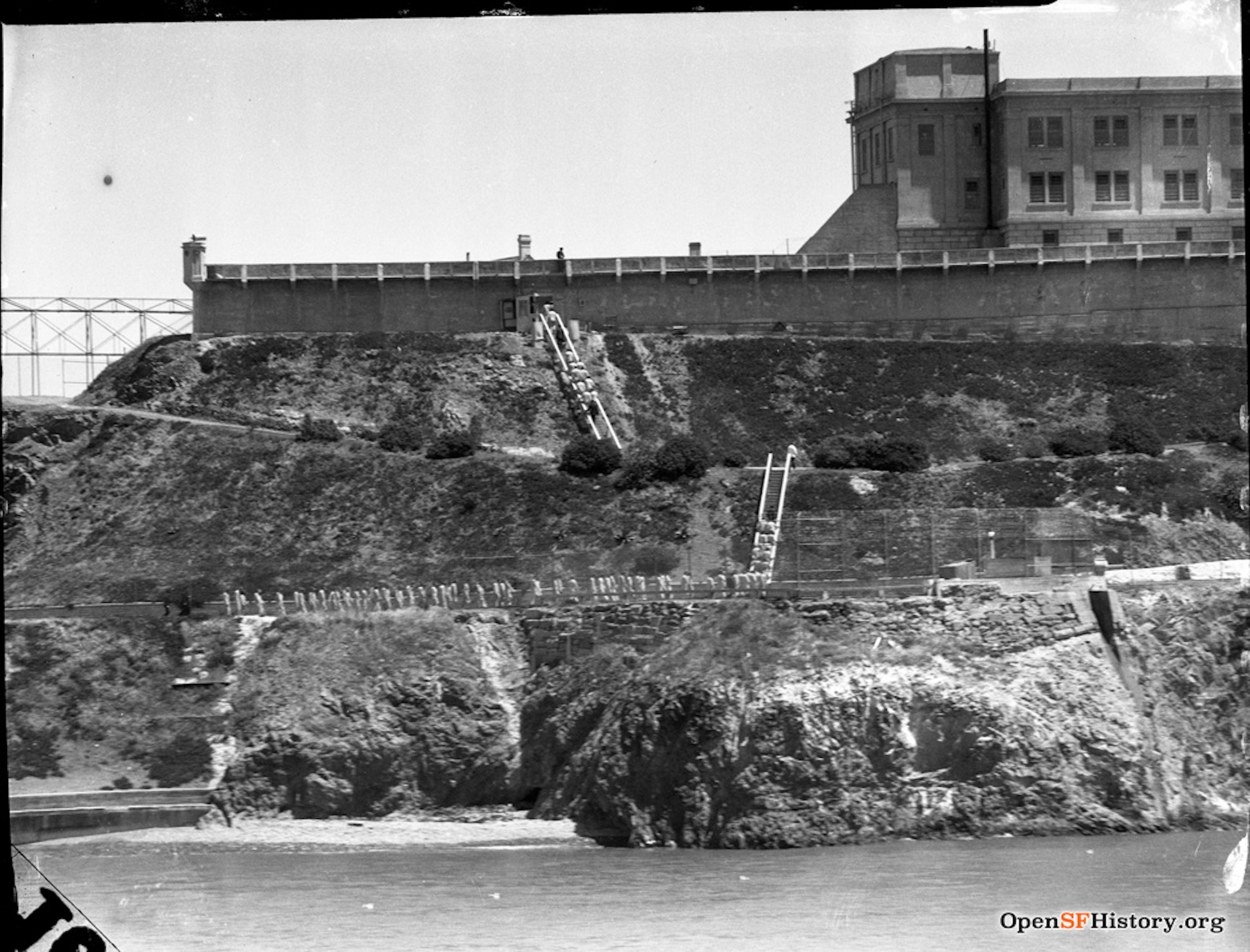

On Jan. 13, 1939, five prisoners managed to saw through the bars of their individual cells in D block, get to the island’s western shoreline, and fashion a raft out of discarded lumber. Ultimately, two escapees were shot (one fatally) by guards, one fell from a cliff edge (and survived) and the final two were peacefully captured wearing only their skivvies.

This was by no means the first escape attempt by Alcatraz prisoners, but it represented a final straw for officials who were increasingly concerned that Alcatraz posed a security risk, as well as a PR problem for San Francisco.

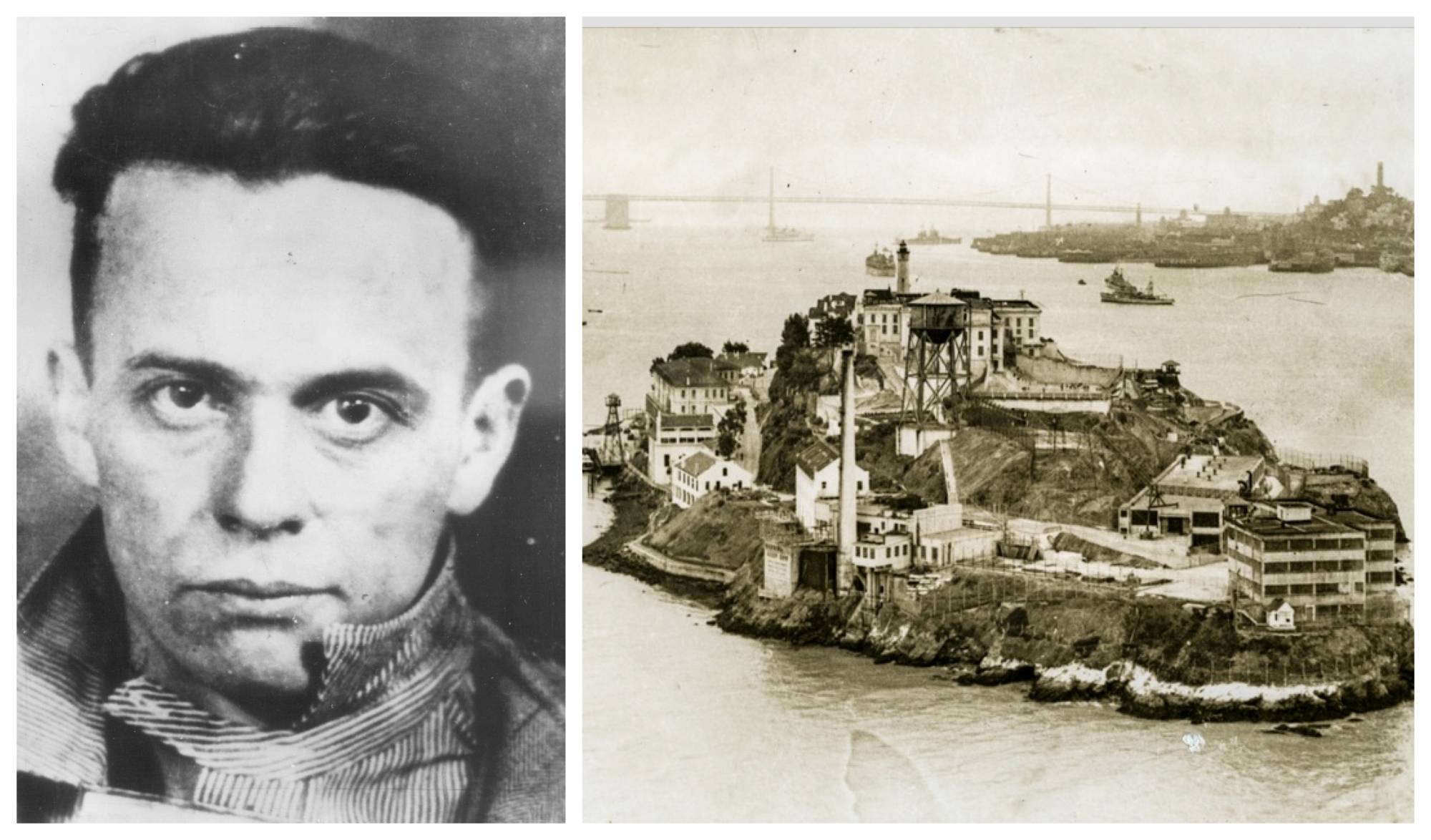

The 1939 escape crew was made up of a coterie of robbers, kidnappers and murderers, led by 40-year-old Arthur ‘Doc’ Barker, who ultimately lost his life. Barker’s associates were Dale Stamphill, 27, Rufus McCain, 36, Henry Young, 28 and William Martin, 25. Barker’s escape plan was said to be inspired in part by the escape of Theodore Cole and Ralph Roe, who made it off Alcatraz island two years prior. Cole and Roe were presumed drowned by authorities but their bodies were never found, leading many prisoners to believe the duo had made it to freedom. (The fact that escapee John Paul Scott successfully swam to Fort Point in 1962 later validated this theory.)

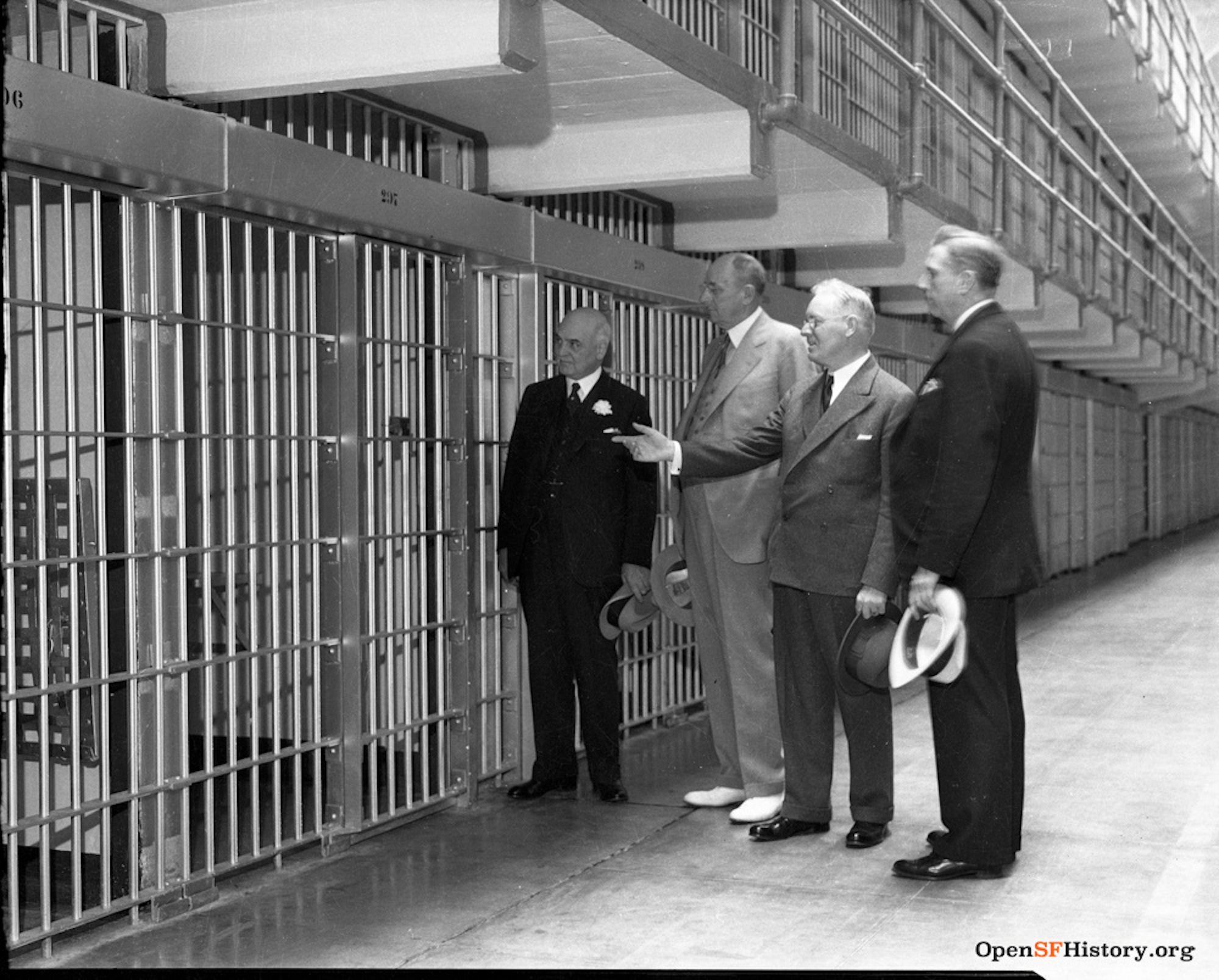

The very same day Barker’s escape attempt happened, Alcatraz warden James A. Johnston took the unusual step of publishing his own account of events in the San Francisco Call Bulletin. Unfortunately for Johnston, his surprisingly frank summary wound up increasing existing concerns about the security of Alcatraz.

Johnston wrote:

When I was awakened, it was so foggy that I could scarcely see to make my way to the cell block. It was really wool thick. We found that the men had escaped from the cell block by cutting through the bars of an exterior window and dropping nine or ten feet to the ground outside … As for how the men got the saws or other tools with which they cut their way out — that’s what we’re trying to learn. So far, we have no idea.

Two days later, a quote from Johnston in the San Francisco Examiner made the prison staff sound even more inept: “We were scurrying all around, and they were scurrying trying to escape us,” he said. “One minute we could see them, and then we couldn’t.”

More sensibly, Johnston explained to the press that Barker and Stamphill were shot when they made a run for the water after guards shouted a warning for them to stop. Stamphill took bullets in both legs, while Barker took one in the eye and later died in the prison hospital. (Horrifyingly, it was reported that Barker “did not lose consciousness” after he was shot.) McCain and Young escaped injury by surrendering, and Martin was later located hiding elsewhere on the island.

If Johnston’s honesty about the chaotic nature of the escape attempt raised eyebrows, the Examiner’s coverage made things infinitely worse. The newspaper carried multiple articles written by a former Alcatraz inmate named Patrick Forrest Reed. Reed’s first exposé, published on Jan. 15, 1939, claimed that he personally had seen visitors repeatedly carry bars and wrenches through the prison’s metal detectors without guards noticing. Reed also said claims that Alcatraz’s cell and window bars were hacksaw-proof were “baloney.”

Finally, Reed wrote in detail about the incompetence of some of the Alcatraz guards:

I’ve seen a guard on the catwalk dead to the world. I came out of the kitchen at 3 o’clock in the afternoon and you could hear him snoring all over the block. There he sat with his feet propped up on the bars of the cage and his sawed off shotgun leaning against the bars on the cell house side. Any con could have stepped up on a desk below the catwalk and snatched the gun … Although it’s strictly against the rules, some of the guards over there have been known to drink.

Reed even alluded to possible corruption within the prison’s walls. “To get from their cells to the window they went through, those five cons had to pass down a long corridor, turn a corner within 20 feet of the catwalk screw and then go through a locked wire gate,” he explained. “You tell me how they got a key to that gate and maybe I’ll tell you how they did it without being seen or heard when it’s so quiet a cough sounds like a cannon shot.”

The terrible press coverage didn’t stop there. In the days after Barker’s death, it was reported that the coroner, T. B. W. Leland, was refusing to release Barker’s body to the undertakers assigned to handle the burial of Alcatraz prisoners. Instead, and in direct opposition to the wishes of prison officials, Leland was awaiting instruction from Barker’s father in Missouri.

(Leland clarified his opposition to all things Alcatraz months later in the San Francisco Call Bulletin. “Alcatraz prison is a blotch on San Francisco’s name,” he said. “The government ought to ship all those gangsters out to the desert and give the island back to San Francisco as a park or a playground.”)

Things continued to get worse with the Jan. 24 inquest into Barker’s death. It concluded with a definitive “recommendation that San Francisco seek removal of [the] penitentiary from San Francisco Bay.” (A contributing factor may have been that Barker was not the first prisoner killed on the island. Thomas Limerick was shot to death in 1938 after killing a guard with a hammer, and Joe Bowers was killed in 1936 while climbing a chain link fence.)

By June 7, 1939, U.S. Attorney General Frank Murphy was campaigning openly for the closure of Alcatraz. The San Francisco Call Bulletin reported that Murphy was “dissatisfied with what he termed the ‘bad psychology’ bred at Alcatraz, saying that it [was] ‘sinister and vicious.’”

The same article reported that other major figures in favor of Alcatraz’s closure included District Attorney Matthew Brady and Chamber of Commerce President Marshall Dill. Dill reportedly stated: “Alcatraz is one tourist attraction San Francisco would be willing to lose without protest. The attorney general is welcome to move it whenever he wants to and wherever he wants to, and the sooner and farther, the better.”

By that time, even sitting San Francisco mayor Angelo Rossi was opposed to keeping Alcatraz open. “God gave us a great and beautiful harbor, created to free the spirits of men, not to imprison them,” he said. “Alcatraz prison has been a drawback to the city, has brought us no good publicity … I’d be glad to see it go.”

Sheriff Daniel C. Murphy echoed Rossi’s sentiments. “While the prison is not a menace from the standpoint of law enforcement,” he said, “I’ve never liked it here. It mars the beauty of our Bay. It brings us unpleasant notoriety … I’m pleased to hear it is to be abandoned.”

Of course, Alcatraz prison was not abandoned for another quarter century. Instead, after Warden Johnston lobbied officials in D.C., a House appropriations subcommittee awarded the prison $100,000 to make security improvements on the island. Ten more escape attempts occurred before the prison finally closed, resulting in the deaths of two guards and four prisoners.

None of them could have predicted that this blight on the Bay would become one of San Francisco’s most popular attractions.