Ryan Coogler’s Sinners has been the subject of voluminous discussion since its release on April 17. And now that the blockbuster has hit second-run theaters and streaming platforms, even more people are getting a chance to join the conversation around the fictional film’s attention to historical accuracy.

How a 2017 Documentary Lent ‘Sinners’ Its Chinese American History

Sinner’s credits are filled with cultural, language and religious consultants, making it clear that Coogler and his team were determined to get even the most minute details right. The result is a constellation of hyper-specific scenes and references: to hoodoo and African spirituality that survived the slave trade; to racial passing and the one-drop rule; to Irish assimilation into white supremacy; and to the presence and role of Chinese Americans in the Mississippi Delta.

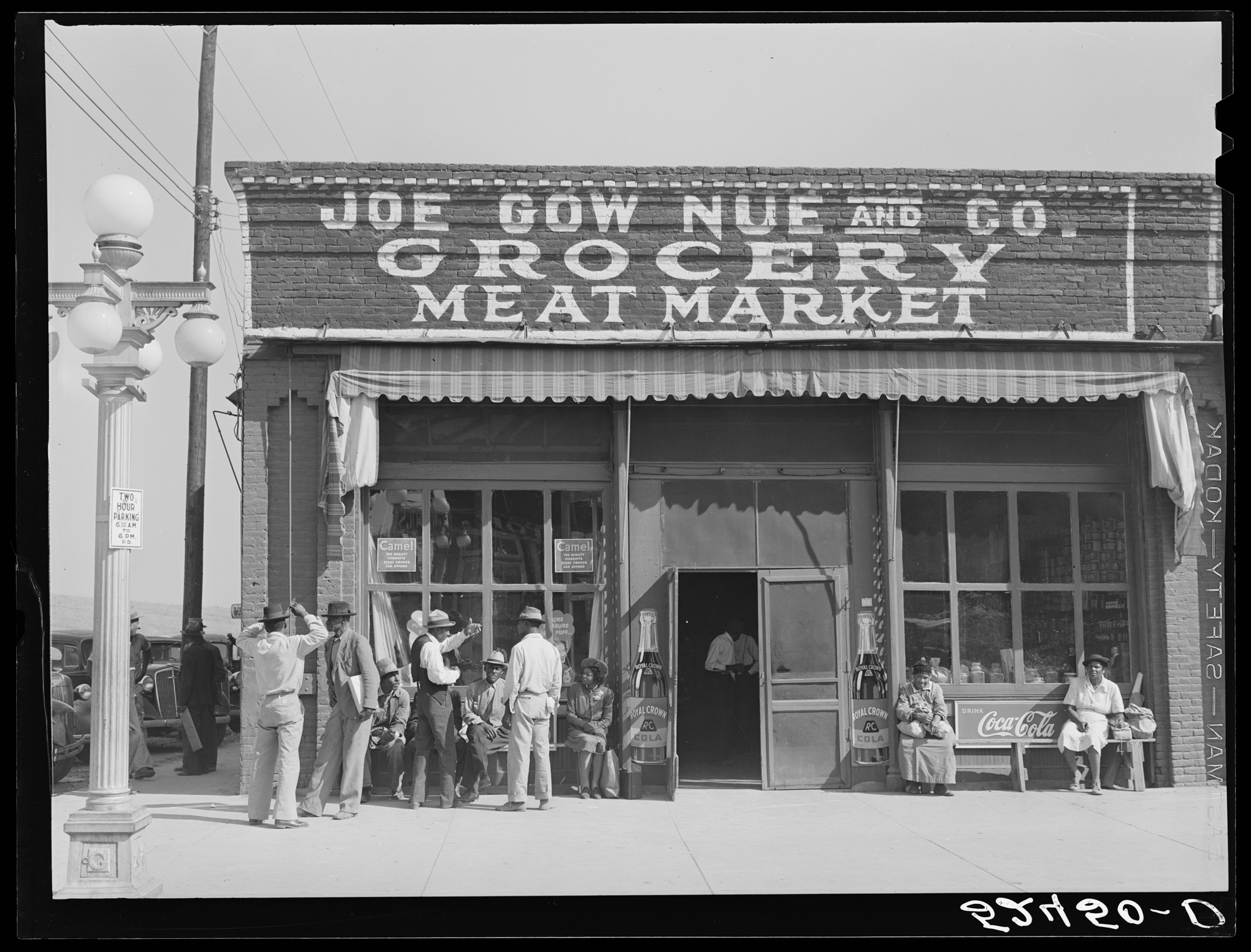

Coogler heard stories of Chinese Americans in the Mississippi Delta from his own family, and recognized in them a unique history of American settler colonialism. In an attempt to do right by that history, Coogler consulted Dolly Li, the journalist and documentary filmmaker behind the 2017 AJ+ documentary, The Untold Story of America’s Southern Chinese. The documentary explores the complex relationships and solidarities forged by Chinese people in the Delta, many of whom operated separate grocery stores to serve the Black and white customers — a manifestation of segregation depicted in Sinners.

Li pitched the story to AJ+ after witnessing misrepresentations of Southern communities during the 2016 election. Born and raised in New York, Li went to college in Texas before moving to Oakland to begin her journalism career. She learned about the Delta community through Adrienne Beraard’s 2016 book Water Tossing Boulders, and wanted to connect with the community it depicted.

But the Delta Chinese community didn’t greet Li with open arms. Burned by reporters in the past, they were skeptical of people wanting to “tell” their story. In a coincidence of in-person timing (Li happened to be in town for a wedding) and a meeting over pizza, community members asked about Li’s relationship to her own Chinese ancestry. “They’re fourth-, fifth-generation Americans,” she says. “So the idea of having Chinese ancestry is kind of like Irish Americans going back to Ireland to try and find their roots from the 1800s.”

They asked Li a lot of questions. “‘What language do you speak? Do you know this word? Have you heard of this?’ And I found that very endearing, because they wanted information from me about their own culture,” she remembers. Rapport secured, the community invited Li and the AJ+ crew into their homes to tell a story many had never heard. A narrative which, seven years after its release, ended up being a critical storyline in Sinners.

Hollywood comes calling

Li first heard whispers about her documentary being used in a casting call from actor friends. At first she thought someone was making an indie and just not telling her about it. Her investigative personality kicked in.

“Somebody better tell me,” she remembers thinking. “Because I’m gonna find out. One of my actor friends was like, ‘It’s Ryan Coogler.’” She didn’t believe them.

When Proximity Media asked if she was interested in being a consultant, Li was hesitant. “It was exciting, but also really nerve-racking, because I also understood the implication of being the main point person for these characters,” she says of Bo and Grace Chow, the film’s husband-and-wife grocery-store owners played by Yao and Li Jun Li. “And because I don’t know what the script is, I don’t know how these characters are going to be manifested on screen.”

When Coogler shared that his family had discovered his father-in-law has Mississippi Delta Chinese ancestry, Li felt relief. “That helped me understand what his curiosity was and his connection to it,” she says.

Coogler and his team’s commitment to detail and historical accuracy made it clear to Li that these characters were not an afterthought. The grocery store owners could easily have been cast as Black or white, and no one would have noted an absence of Chinese American representation in Sinners. Instead Coogler opted to do the more challenging thing, weaving a complex history that forces viewers to confront the violence propelling America’s racial entanglements.

Li saw this choice as an act of camaraderie. “It forces you to reckon with their existence and their humanity becomes undeniable,” she says.

Beauty is in the details

Viewers are first privy to this history when we see Lisa Chow (Grace and Bo’s daughter) cross the street from the Min Sang grocery serving Black customers to the store where her mother is serving white customers.

This seemingly small detail is evidence of considerable effort and intention. (The crew built an entire set for a scene that lasted mere moments.) Yet it’s this scene that sparked some of the more nuanced conversations about the reality, and absurdity, of Jim Crow segregation.

Li worked closely with Monique Champagne, the set designer who created the store, to get everything just right. “Portraying it accurately was so important to her and Ryan and the rest of the production crew,” Li says. “When I saw the store manifest on screen, I screamed a tiny scream out loud. I was just finally seeing all of this work that was put into it come to life.”

Li says this level of attention went into every aspect of the script, and the world Sinners ultimately portrayed. Li Jun Li and Yao told Li they watched her documentary daily to practice their Southern accents. “I was so excited to hear the accents,” Li says. “I thought they did such an incredible job.”

Accents and dialects are crucial elements throughout the film. In the final and most dramatic act, it’s how certain words are said: the vampire Remmick speaks to Grace Chow directly in Taisan, which Li describes as “a really, really old-school dialect.”

“It was the dialect spoken by a lot of early immigrants in the 1800s,” she explains. Remmick speaks not just Grace’s mother tongue, but her village tongue, making the character’s motivations that much clearer. “I think that is probably what triggers the deep fire, anger and fear in Grace,” Li says. “I can see why her character completely lost her shit over it.”

At the end of the day, Sinners is still a vampire movie, with all of the horror and horniness the genre requires. As Li was checking in with everyone, she gave Frieda Quon, whose family grocery store inspired the film’s two shops, a call.

“She was so funny. She was like, ‘Dolly, what do vampires have to do with being Chinese?’” Li laughed, recalling their exchange. “They are Southern ladies, so they’re like, ‘Oh, well, some of the stuff they were saying is more daring than what we were saying.’ A lot of the sexier scenes and sexier lines are making them blush.”

For Jun Stinson Yamagishi, one of the documentary’s producers, the inclusion of the world and history of the Mississippi Delta Chinese in Sinners was a reminder of the power good journalism and storytelling can wield in society. “It made me really think about the importance of doing this work and telling these stories that aren’t being widely told,” Yamagishi says. “They influence historical memory, and then they influence art.”

It all comes down to being able to see marginalized communities as real people, with real stories and lineages worth preserving, remembering and exploring — especially on the big screen. That is what stays with Li the most.

“I think that is one of the coolest parts of the results of this film, that they’re undeniable people now,” she says of the fictional Chows. “Yes, I made this documentary, but it had to be codified by the director of Black Panther for it to be very real to people.”

Dolly Li is currently working on the documentary ‘Martin,’ about chef Martin Yan’s impact on American television and cuisine.