Directly beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, Fort Point’s red brick ceilings and white walls are currently a three-story display of fine art. While the works highlight the golden legacies of African Americans of yesteryear, they wouldn’t be possible without the jewels dropped by the creators of today.

Black Gold: Stories Untold is a free exhibition highlighting the lives of African Americans during the California Gold Rush, the Civil War and the Reconstruction period. Curated by FOR-SITE Foundation founder Cheryl Haines, it features the works of 17 artists, including the Bay Area’s own Adrian L. Burrell and Mildred Howard, as well as artists from around the country like Hank Willis Thomas.

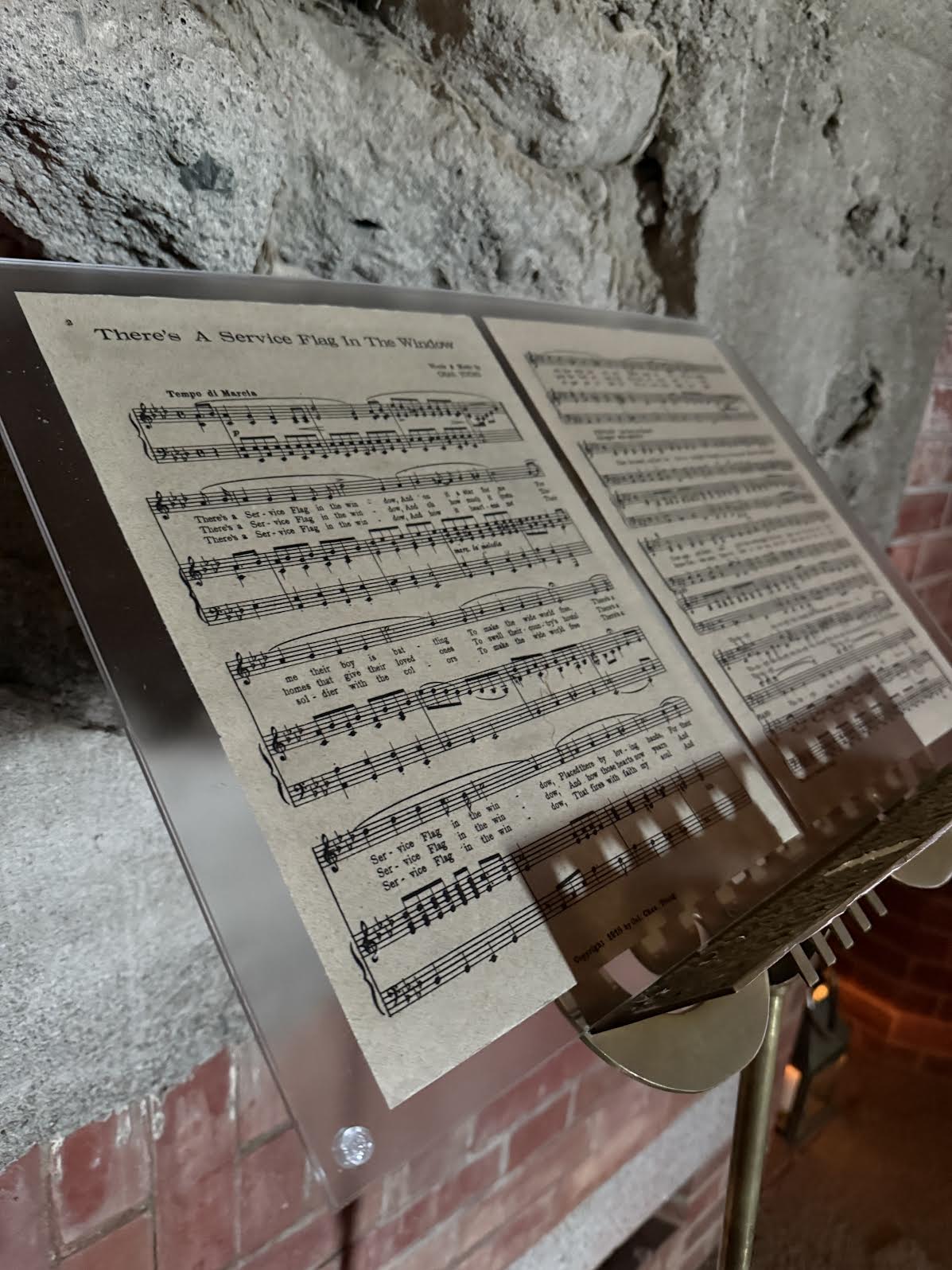

The combination of lingering fog overhead and dim lights inside the oddly-shaped site create a spooky aura. Multimedia pieces play in the fort’s cul-de-sacs while paintings hang near the barracks. Around the building are sculptures, tintype photographs and tiny ships constructed inside of small glass bottles. The stories behind the art reference pioneers, whale captains, millionaires and military leaders; all of them African American people who shared a special connection to the Bay Area, more than a century ago.

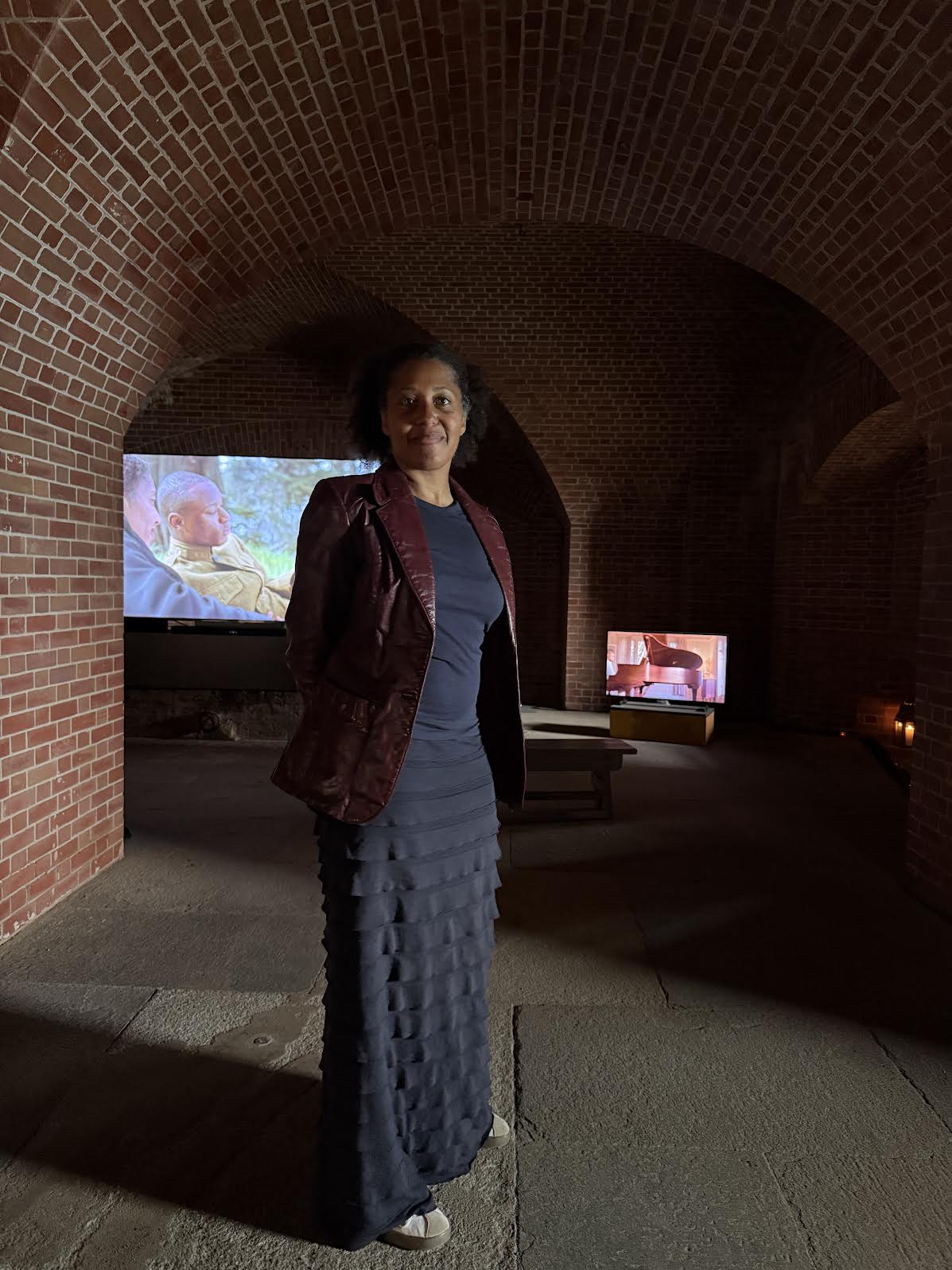

On the third floor at Fort Point, a former military outpost constructed in the 1860s, a seven-minute film shows a montage of one of the highest ranking African American servicemen in this country’s history.

“It’s crazy to me that people don’t know him,” says filmmaker Trina Michelle Robinson, discussing the U.S. Army’s Brigadier General Charles Young, the subject of her short film, Transposing Landscapes: A Requiem for Charles Young.

Robinson refers to Young, a composer and skilled pianist, as a genius. He was a lifelong friend of former colleague W.E.B. Du Bois and mentor to Sgt. Maj. Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., the first Black general in the U.S. Army. Young was also a well-traveled Black man who spoke multiple languages, despite being born enslaved.