Before her death in 2004, the artist Pacita Abad traveled to over 60 countries and made more than 5,000 artworks. Only lung cancer stopped her; she died at age 58 in Singapore after completing a large-scale painting installation across the Alkaff Bridge. Her first major retrospective, which stopped at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2023, was an extensive, colorful tour through Abad’s engagement with art around the globe.

Pacita Abad’s Archive Arrives at the Place Where Her Career Started

Now the Bay Area will have a chance to hold onto the globe-trotting Filipino American artist more permanently. Her archives have arrived at Stanford University, where researchers will be able to consult the records of her career in the place where that very career started.

Abad never intended to stay in the Bay Area. In 1970, she was on her way to Spain with a plan to study law. A brief stop to visit an aunt in San Francisco turned into a life-changing period of time for the young woman from Batanes, the rural northernmost islands of the Philippines.

Between 1970 and 1973, Abad earned a master’s degree in Asian history at Lone Mountain College (later acquired by the University of San Francisco), met and married artist George Kleinman — her first introduction to art making — and later met Jack Garrity, an MBA student at Stanford who would become her second husband and lifelong travel partner.

Since Abad’s death, Garrity has spent years organizing “boxes and boxes and boxes” with the full-time help of his wife, Kristi Garrity, her sister Yanti Darmaji, and part-time assistance of Abad’s nephew, the artist Pio Abad.

In a three-car garage dedicated to the archive, they have sorted items from over 30 years of Abad’s career: exhibition materials, correspondence personal and professional, interview records, image files on CDs and DVDs, materials from the artist’s work with refugees at the Cambodian border, and even Abad’s own copy of the speech she delivered in 1984 when she was the first woman to receive the Philippines’ Ten Outstanding Young Men award.

Some of the estate’s materials previously have gone to the Archives of American Art in Washington, D.C.; the Asian Art Archive in Hong Kong; and the National Archives of Singapore. “We held off from really making a major commitment for the archive,” Garrity told KQED. “It’s not an easy archive for people to understand.” After years building databases and organizing the materials by the places Abad and Garrity lived, the Pacita Abad Art Estate began transferring boxes to the Cantor Arts Center and Stanford University Libraries.

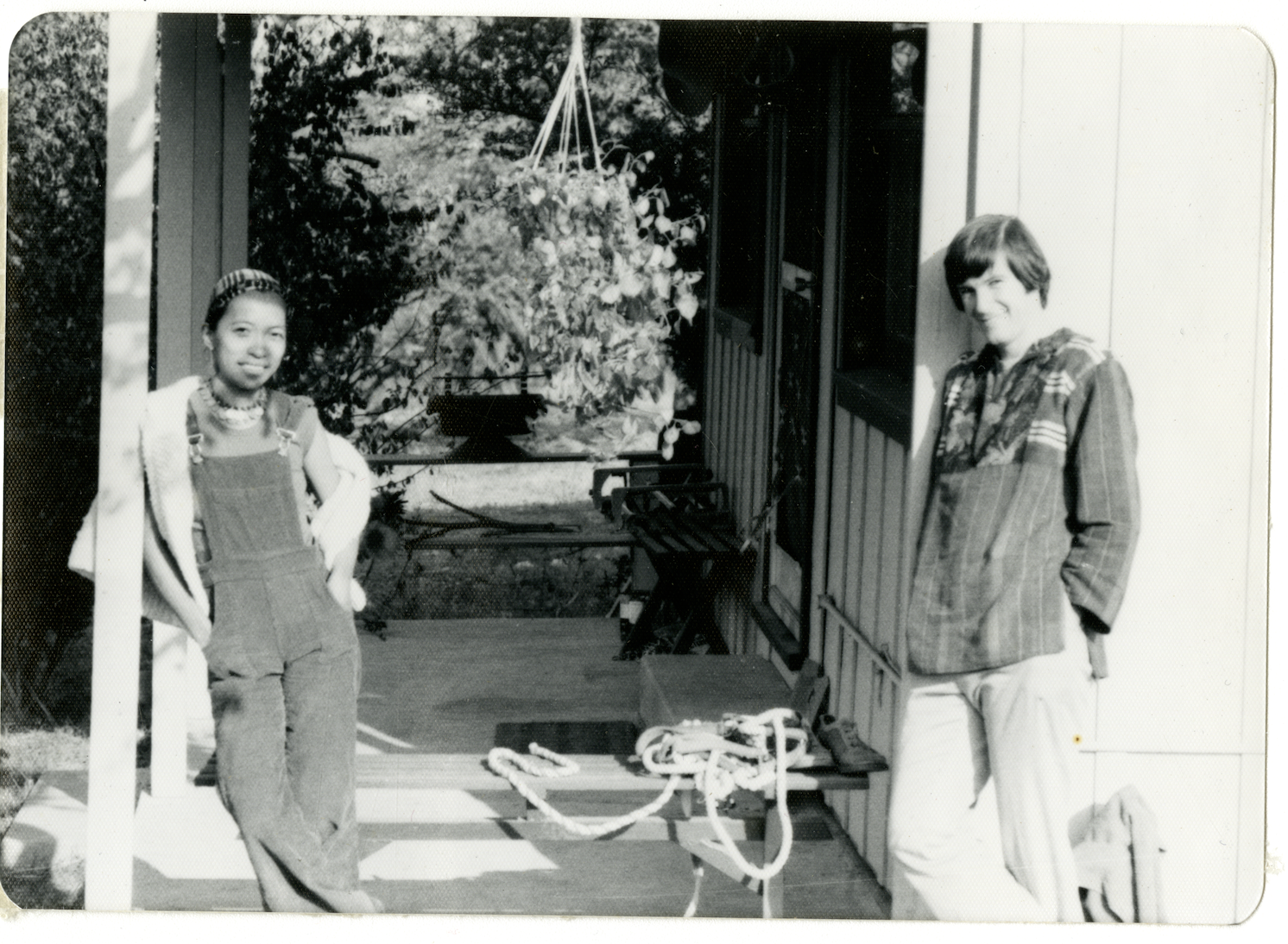

“Stanford made sense,” explained Garrity. “She fell in love with the Bay Area, being at Stanford, and then the large Asian American community… it was a pretty easy decision.” During their time at Stanford, Abad and Garrity lived on a ranch in the Los Altos foothills; he took care of horses, she worked in the medical school and as a babysitter.

Researchers at Stanford will be able to consult photographs of Abad and Garrity in their ranch cabin, alongside Abad’s 1976 painting, Foothill Cabin which depicts Garrity opening a present in their bed set directly on the floor. The Cantor Art Museum, with the Asian American Art Initiative (AAAI), recently acquired Foothill Cabin; and 100 years of freedom: From Batanes to Jolo, a large sewn and painted textile made in 1998; and a print titled If My Friends Could See Me Now, made in 1993.

The Stanford University Libraries Department of Special Collections now holds the archives of Pacita Abad, Ruth Asawa and Berenice Bing, and manages the Martin Wong catalogue raisonné (created with AAAI and the Martin Wong Foundation). With AAAI’s rapidly growing art collection, Stanford’s position as a leading center of Asian American art history studies is cemented. Conserving all of these archives represents a major institutional investment.

“It’s free like puppies,” quipped Lindsay King, head librarian of the Bowes Art and Architecture Library at Stanford. “We’re basically saying we’re going to take care of this forever and you’ll be able to access it forever.” That promise requires “staff to process the archive and make it organized and available to the public.” Processing the 120 linear feet of Abad’s boxes, even as organized as they already are, has required hiring a full-time processing archivist.

“Few institutions are able to take huge archives, because they’re realizing how quickly it translates into money,” said King. But that investment can make history. Literally.

“How do we know stuff is true? And how do we create stories about people we’re interested in?” King asked. “Yeah, either you or someone has looked at the primary sources.”

Veronica Roberts, director of the Cantor, views an archive as a way to correct erroneous stories and repeated misconceptions about artists. “I think what you need the archive for is an actual historical record and a way to get past the reception,” said Roberts. “The way the press first writes about a work can really lock in … I think [the archive] gives us an ability to break free of that reception and to really go back to those original sources.”

Beyond historical correction and new narratives, an archive also can spawn brand-new histories. “Many students are getting inspired to write about artists who nobody has written about,” said King. Providing opportunities to students and scholars to study and write Asian American art histories has been a key aim of AAAI. King, Garrity and Roberts each mentioned an incoming graduate student who applied to Stanford specifically to work with the Abad archive. It seems like the investment is already beginning to pay off.

“That’s how scholarship will change,” said King. “If there are more contemporary artist archives available and people write new things about new artists. That’s how it becomes part of the written record.”