A woman packing up her life to escape the cataclysmic flooding and sinkholes that have rendered San Francisco “a city on a sheet of Swiss cheese” suddenly finds a note under her door. It bears three unignorable words: I need help.

This is the inciting spark of Susanna Kwan’s debut novel Awake in the Floating City. In it, Kwan imagines the city engulfed in flood water. Endlessly, suffocatingly wet. Most have fled or died. It is illogical, difficult, to remain, but the story revolves around two people who do: Bo, a struggling young artist; and Mia, her 130-year-old neighbor.

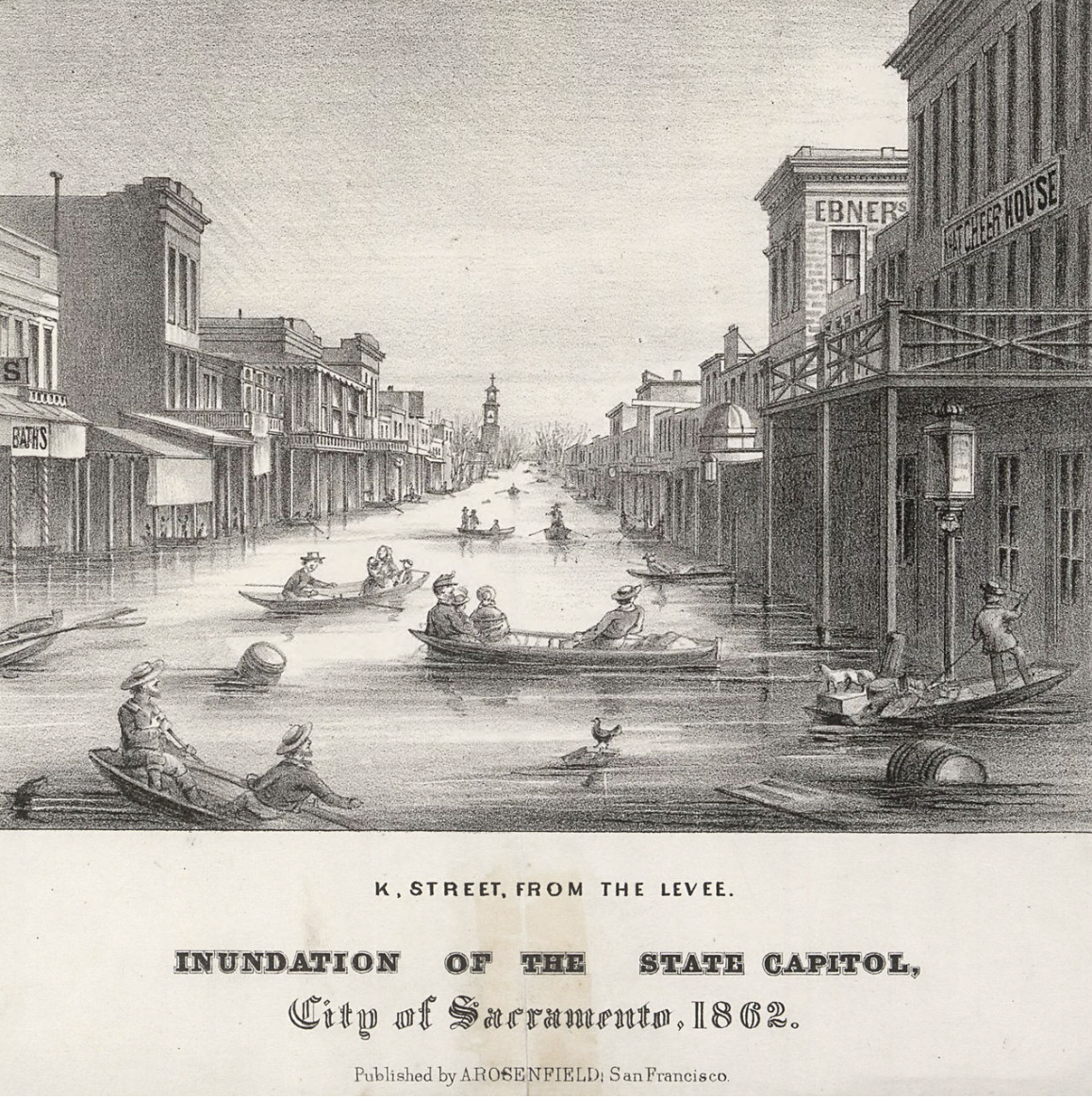

Awake in the Floating City is a terrifically polished debut and addition to the growing genre of climate fiction — contemporary creative works contending with the very real ways climate change has and will continue to alter the human landscape. Kwan, a third-generation San Franciscan, currently lives in the Richmond District. It was her hometown’s ancient and recent history of climate emergencies and natural disasters that provided welcome inspiration for her first novel.

“I was here for the recent wildfire seasons, the orange day, [and] even as a kid, there was a six or seven-year period of extreme drought. There was a big earthquake,” she recalls. “These big events affect everybody here and really shape the culture.”

This lived reality of calamity served as both fuel and research. “When I started the book, it seemed implausible that there would be years and years of rain,” says Kwan. “In the last few years, we’ve had these weird winter seasons [where] it seemed like it rained every single day for months on end.”