Sergei Loznitsa smiles and laughs through our entire Zoom conversation, which I find extremely disconcerting. You see, his invaluable archival documentaries (The Natural History of Destruction, Babi Yar. Context and State Funeral) revisit dark chapters in Eastern European history, while his unflinching fiction features (such as In the Fog and My Joy) are even more grim.

Sergei Loznitsa Screens His Studies of Eastern Europe During Wartime

The antithesis of the chain-smoking nihilist I expect, Loznitsa has the amiable bearing of a philosophy professor. That demeanor will play well when he returns Jan. 30 through Feb. 8 for a residence at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive near the UC Berkeley campus, especially if moviegoers welcome him as an emissary from one of the world’s hot spots, or as a journalist, instead of (or as much as) an artist.

Six of the eight films in the lineup were made since Loznitsa’s previous visit to Berkeley in 2017. The Invasion, which premiered last May at Cannes, launches the series with a measured record of contemporary Ukrainian life during wartime. Employing a fixed, respectful camera, the doc observes older people queuing to refill water bottles, teachers guiding young students through difficult realities, a couple’s poignant marriage and a few heartrending funerals.

“For me, first of all, it was very important to make an archive,” Loznitsa says. “Everything which was shot, I will keep. Second, I would like to show how people survive in these circumstances, how ordinary people live everyday life. Third, I would like to share my pain with the spectators.”

Loznitsa doesn’t use voice-over narration or conduct interviews, which lends his nonfiction work the veneer of objectivity. He forthrightly declares, though, that he’s not presenting the truth but providing his opinion and point of view.

“I’m not a journalist, who has to share information. It’s not information, what I present. It is something which I built. This is my discourse. It’s my thought, which develops in my film, what I’m thinking about.”

The most essayistic sequence in The Invasion opens cryptically with a bookstore employee carrying bundles of used books left outside the front door. We come to see that the authors are Russian, including Pushkin and Dostoevsky, and so many books have been dropped off that a truck takes them away to be pulped.

The filmmaker takes the time to note this less-heralded casualty of war, namely the decline in understanding and empathy that accompanies demonizing and destroying cultural works. You won’t be surprised to learn that Loznitsa, who unambiguously opposes Russia’s incursion into Ukraine, criticized boycotts of Russian films and filmmakers.

Loznitsa was born in Belarus when it was part of the Soviet Union, raised in Ukraine and — after a stint as a research scientist at an Estonian university — graduated with a degree in producing and directing from the Russian State Institute for Cinematography in Moscow. He and his family moved to Germany in 2001; he was speaking with me from Vilnius, Lithuania, where he also has a residence.

So from the beginning of his career Loznitsa has been perfectly situated, by birth, geography and sensibility, to examine and chronicle seismic, far-reaching events.

“My films are about Soviet or Russian history, or about recent history, and I cannot say this is very light history. I know that I have a talent to make a comedy,” he says with a chuckle. Perhaps, he muses dryly, the films and topics he chooses for reflection are necessary for treating the material humorously in the future.

“When we understand what happened with us in the past, and what we repeat now, [we can recognize] what kind of circle we are just passing in our life. I found so many similarities between history that happened after the October Revolution — it wasn’t a revolution; it was a coup d’état, let’s say — and history which is still continuing now. If we are talking about this [current] Russian aggression against Ukraine, it happened already in 1918 when the Red Army came to Ukraine and occupied this territory in two years, or returned this territory to the Russian Empire and rebuilt the Soviet Union.”

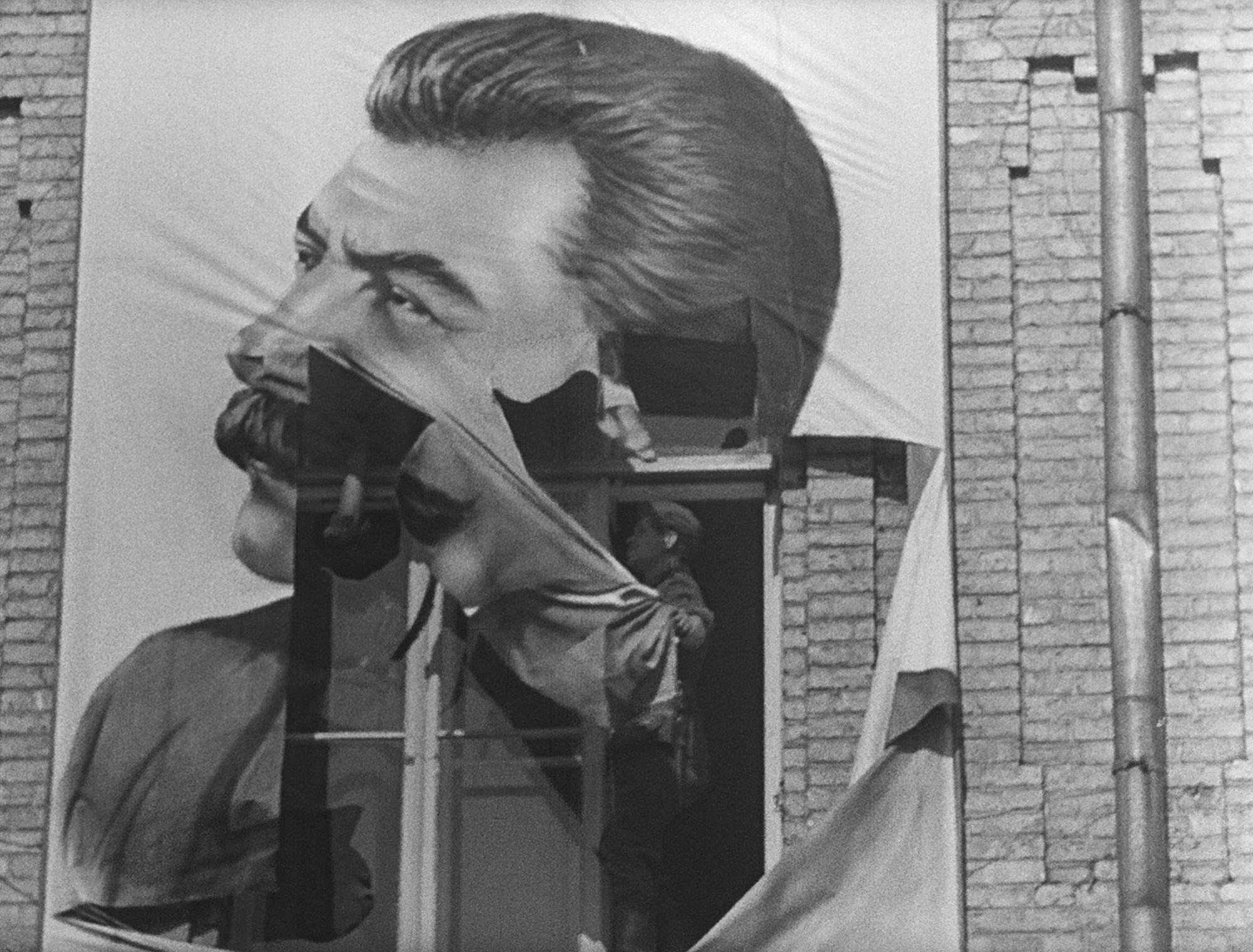

The BAMPFA series includes Loznitsa’s trilogy of mesmerizing docs constructed from acres of archival footage. State Funeral (2019) immerses us in the national state of mind of a propaganda state through the reactions, rituals and rites following the 1953 death of Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin. Babi Yar. Context (2021) situates a horrific war crime — the 1941 shootings of more than 30,000 Ukrainian Jews by Nazi units and Ukrainian police over two days — and recounts the long chain of events that enabled people to accept the mass murders of their neighbors.

From a structure and editing standpoint, The Natural History of Destruction (2022) is arguably Loznitsa’s most complex and intriguing work. His ostensible subject is the bombing of civilians, by both Germany and the Allies, during World War II (which is brutally and cruelly echoed in Russia’s ongoing nightly drone and missile attacks on Ukrainian cities).

But the airplanes that dropped those bombs in WWII were built by civilians. It’s difficult to make the case that civilians shouldn’t be drafted into the war effort — especially since everyone involved believes they’re defending their homeland; no aggressors here! — just as it’s hard to argue that it’s fine for defenseless families to be annihilated from above.

Perhaps all war is total war, and it has been that way for 85 years. We are in the thicket of compelling moral questions, although we might table that discussion out of compassion for the people in Kharkiv, Gaza and elsewhere who are presently and continuously terrorized.

Loznitsa has such a kind, genial way of talking about the heaviest themes that I am reminded that the very act of making art, even art about depressing topics, is life-affirming.

“This is what I believe,” he concurs, “that very strong, deep emotion that people get after watching a film can push them to think, and can transform [them] a little bit, slightly move them toward the lighted part of the universe. To be more kind to people. Cry during the film and after that, be better.”

Sadly, as a student and chronicler of history, Loznitsa can imagine a scenario where his work could have practical applications.

“Maybe in my films I describe some situation which somebody in the future will face and will know how to be because he or she already has thought about that,” he says. “This is how art helps us.”

He laughs again, this time with an air of self-deprecation. “I think every artist is looking for a way in his work that can reconcile him with a very dangerous and not pleasant world.”

Sergei Loznitsa will be the filmmaker in residence at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive Jan. 30–Feb. 8, 2025, appearing in person at all screenings of his films.