Inside an office on Third Street, a main thoroughfare in San Francisco’s Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood, lifelong resident Arieann Harrison reflects on the legacy left behind by her late mother Marie Harrison.

“My mother was deemed the ‘Mother of the Movement for Environmental Justice,'” Arieann says proudly.

Marie Harrison spent a large portion of her life advocating for healthier communities and pushing for legal accountability from the large institutions that polluted her neighborhood—an area that has been home to working class people of color for generations, especially African-Americans.

Along with a handful of organizations and community volunteers, Harrison successfully fought for the closure of a toxic PG&E power plant in 2006. She was also part of the team that sounded the alarm about pollutants at the Hunters Point Shipyard, the botched clean-up job, and the lingering impact on the surrounding community. She organized residents, spoke at City Hall and even once chained herself to a fence in protest.

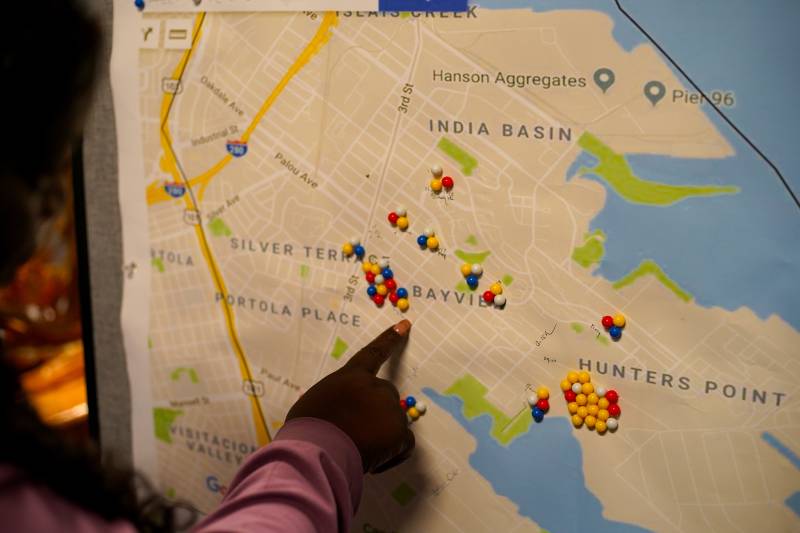

In honor of her mother’s efforts, Arieann Harrison is continuing the fight against environmental racism. She is the founder of Can We Live, an organization that is working with local residents to screen them for toxins and install devices to monitor airborne pollutants. Can We Live also offers scholarships for students interested in studying environmental justice.

This week we talk to Arieann Harrison about growing up on toxic terrain and how her work doesn’t fall far from the family tree.

Below are lightly edited excerpts of my conversation with Arieann Harrison.

HARSHAW: In the early 2000s, Marie Harrison and community groups, such as The Hunters View Tenants Association and Greenaction, worked with residents to protest a local PG&E power plant that was spewing toxins into the Bayview-Hunters Point community, toxins that were directly impacting her family’s health.

HARRISON: She was concerned about my kids, first of all. You know, my youngest, my baby was having nosebleeds and stuff like that. I was like a new mother. So I’m doing everything that I think is right. I’m feeding the baby and all that kinda stuff. My baby kept on losing weight. It was like going in reverse, and he would always spit up his food.

My mother said it got something to do with that black soot that keep on spewing up and spewing up in the community, ‘cause my child is not the only one that is sick or having some problems with breathing and different stuff like that. There’s other community resident members that are having the same issues.

HARSHAW: Marie Harrison wanted elected officials and residents alike to be aware of what was happening in the neighborhood. Her passion about this issue inspired her to take radical actions. One time she chained herself to the front gates of the power plant.

HARRISON: [Laughs] I remember My mom said, I think I’m going to jail. [laughs] I think I’m going to jail [laughs] you know her and her crew, you know, chaining themselves to a fence. I was like, really?

And my mother didn’t have no record, or nothing like that, so that was kind of a big… that was a big deal.

HARSHAW: Were you out there with her?

HARRISON: No, I took my, took my son and went home. Next thing I know, I’m coming back down the block and she already gone. They taking her to jail, you know. My mother was stubborn. My mother will tell you “yeah” and do what she gonna do, right, and I’m the same way bout it [laughs].

HARSHAW: In her later days, I’ve seen the images of [your mom] with the oxygen tank and speaking about what’s happened in the community down at city hall. And so at that point, in her fight, how did that inspire you even further to get into this work?

HARRISON: My mother was diagnosed with a respiratory lung disease. When they showed the pictures, the X-rays that they took of her, it said it looked like somebody physically went in there and scratched up her lungs, you know, like she was attacked from the inside. My mother didn’t smoke cigarettes. She didn’t drink, none of that stuff.

I was really, really, really angry. I was very upset. But, you know, sometimes you gotta turn your anger into a lighter fluid, right? Turn it into kindling. You gotta throw it on the fire and watch it burn and turn it into fuel. Right?

Rightnowish is an arts and culture podcast produced at KQED. Listen to it wherever you get your podcasts or click the play button at the top of this page and subscribe to the show on NPR One, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, TuneIn, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.