Just a few miles northeast of the California state capital, in the city of Folsom, a public recreation area has been recently renamed Black Miners Bar after decades of being called Negro Bar.

The tree-laden piece of land sits adjacent to the American River, between Folsom Lake and Lake Natoma. Nowadays, it’s a place where people gather for boating and swimming during the summer months, while woodland creatures like birds, squirrels and snakes make it their home year-round.

Historically, the site is known as a place where African American miners were relegated to panning during California’s Gold Rush of the mid-1800s, but it wasn’t just miners who settled there.

There were also people who worked in industries that supported the miners, and those stories are still being explored.

After some debate about the origins and connotation of the park’s name, in the summer of 2022 California State Parks unanimously voted to change the name of Negro Bar to Black Miners Bar temporarily, while the department conducts more research into the true history of the area.

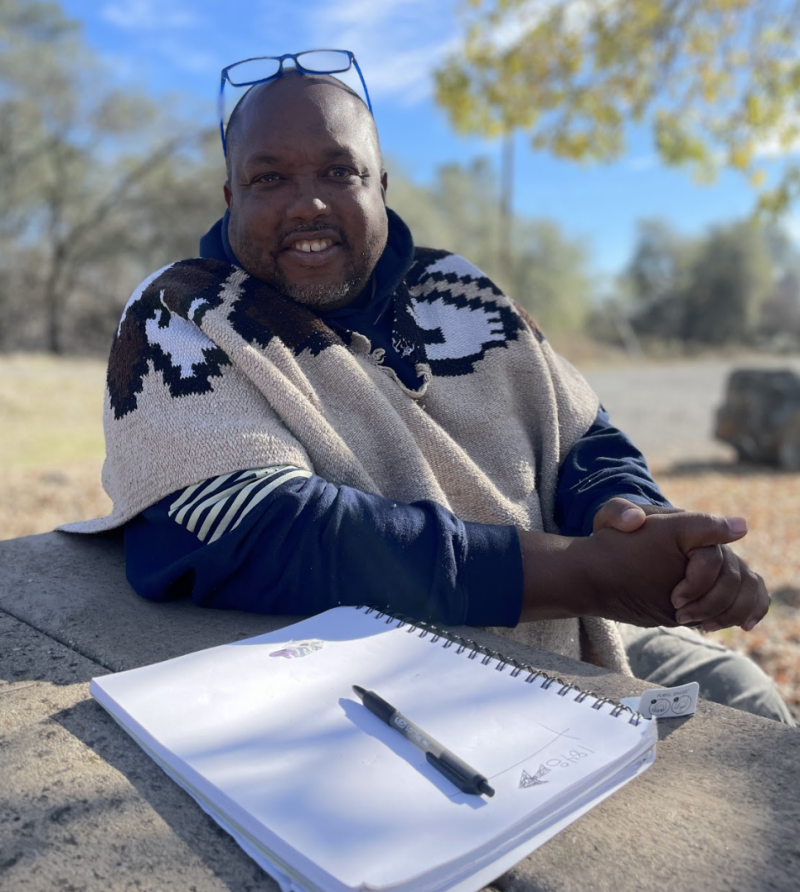

For more on what actually transpired on this piece of land we talk to Susan D. Anderson, History Curator and Program Manager at the California African American Museum, and one of the lead researchers on the project. We also talk to Michael Harris, a historian and chair of the Friends of Negro Bar community group.

As we simultaneously celebrate Black History Month and kick-off our series on land and life in Northern California, there’s no better way to start than by exploring the real story of one of the first places African Americans called home in California.

Below are lightly edited excerpts of my conversations with Susan D. Anderson and Michael Harris.

PENDARVIS HARSHAW: According to the U.S. census from 1850, there were 500 to 600 residents at the site where Black Miners Bar is now.

So how was it that Black folks arrived on the West Coast in the first place?

SUSAN D. ANDERSON: People of African descent have been coming to California since people have been coming to California. People of conquest in Spain, they brought African descended Spaniards with them who were navigators, soldiers, sailors, priests, enslaved people.

HARSHAW: And once the U.S. seized California, the migration of Black people happened for other reasons.

ANDERSON: The country was in a crisis, in a crisis over slavery. And the year that California came into the United States, African-Americans who were freed, who lived in places like Pennsylvania or New York or Massachusetts, they would be kidnaped on the streets by the lawful exercise of the Fugitive Slave Law. And so people became very interested in what were the possibilities in the West. Will we be able to escape this kind of danger for ourselves? So African-Americans were very interested in California as a possible beacon of freedom.

HARSHAW: Though California was a refuge, Black folks still faced racial discrimination, which is what led many black miners and their families to congregate in their own area.

HARSHAW: For Michael, he really wants people to understand that this settlement is more than just Black folks searching for gold, it’s about Black folks searching for liberation.

MICHAEL HARRIS:The people that were coming out West were yearning to be free. They were looking for freedom and a place to, like, raise their families and a place to be human beings and that was afforded to them in this area.

HARSHAW: Which factors into why Michael thinks “Black Miners Bar” as the name isn’t fit to describe this settlement that included more than just miners. For him he’s okay with it remaining “Negro Bar”.

HARRIS: Some people, they want to use 2022 nomenclature and ideas and values to talk about an 1848 story. There was no one running around talking ‘I’m Black and I’m proud.’ So to call it Black Miners Bar, you know, completely erases and like disparages that there were people of African descent here trying to figure out how to be free and set up towns, not just one. I mean, towns all up and down the American River.

HARSHAW:Those towns were not too far away from the Black Miners Bar area. There were black settlements in Sacramento, Marysville, and El Dorado county. In creating towns for themselves in these California cities, Black folks also established their own institutions.

Rightnowish is an arts and culture podcast produced at KQED. Listen to it wherever you get your podcasts or click the play button at the top of this page and subscribe to the show on NPR One, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, TuneIn, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.