Ask anyone in your life to draw you a quick doodle of a ghost, and they’ll more than likely present you with some variation of the bedsheet ghost. Round on top, wiggly on the bottom, with a couple of eyeballs/eye holes. If they’re feeling extra cute, there may be a mouth too. (Or even a tongue if the ghost emoji has served as a recent inspiration.)

Why Ghosts Wear White Sheets (And Other Spectral Silliness)

This specific image of ghosts-as-white-sheets has been engrained in our culture for centuries and, until fairly recently, it was considered genuinely terrifying. The root of it lies in the fact that, up until the 19th century, the dead were almost always wrapped in burial shrouds, rather than placed in coffins. In poorer families, the recently deceased were simply wrapped up in the sheet from their death bed, and secured inside by a knot tied at either end.

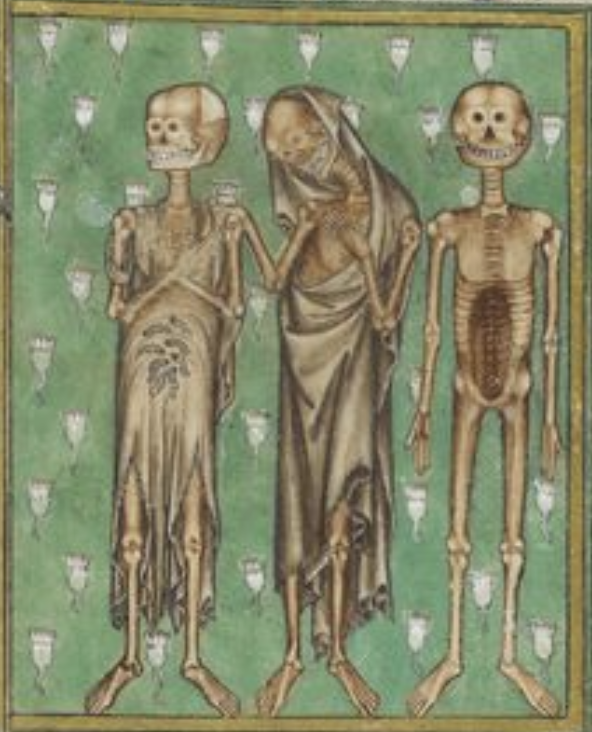

In the 1300s, ghosts were often presented as skeletons draped in their shrouds, as this depiction from The Psalter of Robert de Lisle (created some time between 1308 and 1340) demonstrates. In the story of “The Three Living and the Three Dead,” three spirits/corpses warn three noblemen to live virtuous lives or be damned. (The maggots are a nice touch, don’t you think?)

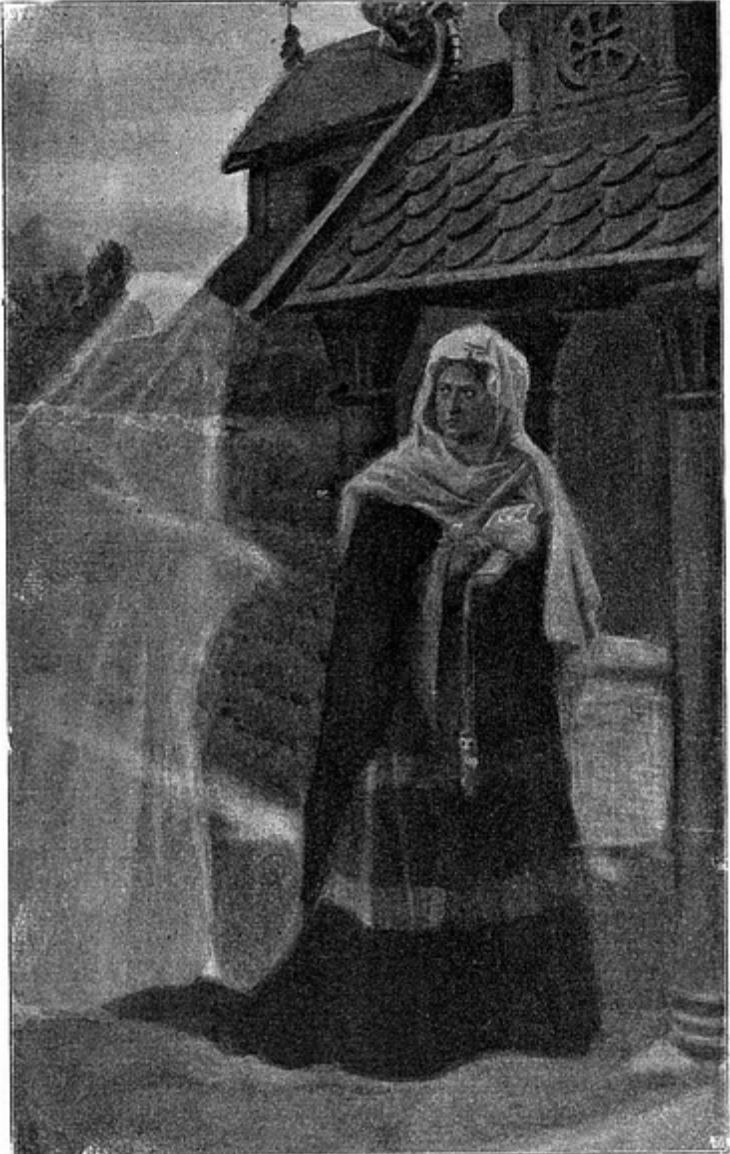

By the 1400s, people reporting supernatural phenomena almost always described apparitions as being clad in their death shrouds. This depiction was, by then, so widely accepted that, an entire subset of English thieves began donning white sheets and pretending to be ghosts. These undead disguises had the dual benefit of hiding the thieves’ true appearances, while also scaring their targets into handing over money. Even after multiple ghost impersonators were exposed by the authorities over many years, the public continued to believe that unhappy spirits roamed the Earth clad in their burial shrouds.

In 1804 London, a bricklayer named Thomas Millwood was mistaken for a malevolent ghost, and shot and killed by a man named Francis Smith. Smith had seen Millwood’s pristine white work uniform, complete with white apron, and assumed he was a ghost. (Local residents and a night watchman had recently reported being terrorized by some such spirit.) At Smith’s subsequent murder trial, Millwood’s wife said her husband had been mistaken as a ghost by three other people before the shooting, and that she had asked him to start wearing an overcoat, to no avail. Smith was found guilty of murder and sentenced to one year of hard labor. The “ghost” haunting the neighborhood was later exposed as a local man exercising some personal revenge.

Millwood’s tragic death by no means shifted the general public’s ideas about be-sheeted ghosts (or shooting at them). In 1889, one Missouri newspaper conducted a poll of its readers, asking if they believed in spirits. A reader, J.W. Wills, wrote in to say that he had seen two ghosts in his life. One of them, he claimed, was a large white object with long horns that he would have shot if he’d had his pistol with him. Another reader, Professor B. F. Heaton wrote in to say that ghosts “are nearly always white, although some of the authorities admit there are dark ones. I should say, however, that the genuine ghost is always white and always makes its first appearance at the haunted spot at precisely 12 o’clock midnight.”

These ideas were compounded by theatrical presentations of spirits and hauntings throughout the 19th and into the early 20th century. On-stage ghosts varied enormously, from simple depictions of actors in white face paint or armor, to tricks involving mirrors and trapdoors. Theater scholars argued that unadorned actors playing ghosts were able to elicit greater sympathy from audiences. It followed that ghosts in white sheets were scarier. And that imagery carried into the depictions of ghosts in Victorian spirit photography—a trend that didn’t disappear entirely until the 1930s.

If bedsheet ghosts had become something of a casual amusement by the end of spirit photography’s heyday, it was children’s cartoons that took that element of fun and ran away with it. In 1937, Disney released The Lonesome Ghosts, an eight-minute cartoon in which Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck and Goofy are a ghost extermination team assigned to clear a house of spirits. The cartoon ghosts were transparent, with hats and expressive faces. But their loose outfits, including capes, were clearly fashioned out of sheets. It was a creative element that added a cute twist to the ghosts of old. When Casper the Friendly Ghost arrived in 1939, it was the first major indicator that culturally, ghosts had become figures of fun.

In 1957, one Popeye cartoon depicted the sailor eating his spinach to annihilate a bunch of ghosts on a haunted ship. The episode ended with Olive Oyl sewing the ghosts’ shrouds together to make a giant sail. By 1969, Scooby Doo and the gang had begun exposing ghosts and ghouls as human frauds. And, of course, the opening credits of that show featured a bedsheet ghost.

Scooby Doo’s tone fit the times: there was an overwhelming sense that bedsheet ghosts, along with other superstitions, should be relegated to the realms of old-fashioned tomfoolery. On Nov. 8, 1964, North Carolina’s News and Observer declared: “Styles in ghosting are changing. Dwindling into obscurity are the old fashioned groaning, flapping, bedsheet ghosts and the simple white objects which jump out of dark places and say ‘Boo!’ These are fading along with simple haunted houses, graveyard ghosts and headless horsemen.”

If the bedsheet ghost had one last moment of chilling repugnance, it was in Whistle and I’ll Come to You, a 1968 horror produced by the BBC. In it, a seemingly sentient sheet was presented in several scenes in a manner that was truly unsettling. The closest we’ve come to that since was in 2013’s The Conjuring which managed to deliver a genuine scare via a single sheet hitting an anonymous, invisible body.

These days, bedsheet ghosts are more likely to be found cutely adorning clothes, decorations and candles on Etsy, than they are giving anyone an actual fright. But, at this time of year, it’s worth remembering who the bedsheet ghosts once were and who they represented. After all, you never know when the scary ones might come back.