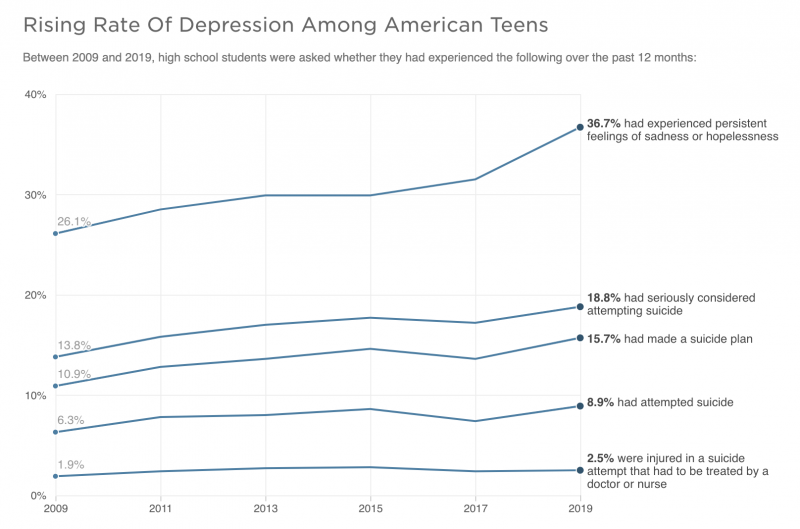

“There is an association between the two,” Primack says. “Just meaning that if you put people into equal buckets in terms of how much social media they use, the people who use the most social media are also the people who are the most depressed.”

But unlike cigarettes, which he says have no useful purpose, some people have shown positive health outcomes from using social media.

Brain development research in recent years, for instance, found benefits in 9- and 10-year-olds from using social media.

“Social media is very heterogeneous. In some kids it can be very beneficial, and in other kids it can be very detrimental,” said the author of that study, Dr. Martin Paulus of the Laureate Institute for Brain Research. “But we still don’t understand which group of kids benefit from it and which group of kids may be harmed by it.”

Paulus is not confident the social media companies truly want to get to the bottom of that question either.

Several years ago, Paulus gave a presentation at Facebook with a few other researchers who were looking at the effects of social media. He came away from the meeting feeling like the company wasn’t serious about actually having objective research.

“It was more like a face-saving activity,” Paulus said. “Those companies, whether it’s Facebook or other companies as well, they say they want research… But they’re not necessarily interested in research that potentially would show that some of the things that they do are bad for kids.”

It’s a thorny issue to wade into. The company says that it employs hundreds of researchers and that it also supports efforts like Boston Children’s Hospital’s newly formed Digital Wellness Lab and the Aspen Institute’s roundtables on loneliness and technology.

But it has also been criticized for using its platforms for research purposes. In 2012, the company allowed researchers to change what people saw on the platform in order to see how that would affect the nature of what they then chose to post.

The study did show evidence that people’s moods are affected by what they see other people posting, but some saw the exercise as emotional manipulation, and one of the authors seemed to express regret about conducting it after the backlash.

For a company with one of the largest data troves on the human population, this question of how best to conduct research expands to other sectors too. Disinformation researchers, for instance, have long been frustrated by what the company chooses and chooses not to share.

“They could answer questions that we desperately need answered any time they want, and they just won’t do it,” said Ben Scott, executive director at Reset, an initiative aimed at tackling digital threats to democracy. “They’ve chosen, for public relations reasons, not to participate in helping the public interest… And that’s outrageous.”

“God only knows what it’s doing to our children’s brains”

The potential dangers of kids spending hours hypnotized by their screens has been apparent essentially since the social media platforms were created.

Founding Facebook President Sean Parker once described, in an interview with Axios, the company’s algorithms as “exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.”

“God only knows what it’s doing to our children’s brains,” Parker said. “The inventors, creators—it’s me, it’s Mark [Zuckerberg], it’s Kevin Systrom on Instagram, it’s all of these people—understood this consciously. And we did it anyway.”

The problem is compounded by how little government funding is going toward studying the effects of these platforms, relative to how much of each day many Americans spend engaged with the technology.

Funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is mostly focused on curing diseases, but because there is no specific disease officially associated with screen time, experts say it’s difficult to get studies funded by the federal government.

In 2019, Sen. Ed Markey, D-Mass., introduced a bill that would have provided a mechanism for more NIH research on the subject. The legislation had bipartisan co-sponsors and the support of Facebook, but it never made it to a vote.

Without more of that sort of research, parents are essentially left in the dark guessing exactly how much is too much for their kids when it comes to their devices.

“The truth of it, quite frankly, is we are probably living through one of the biggest natural experiments that we’ve gone through with our kids,” said Paulus.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))