I’m obsessed with tales of obsession. Chances are, you are too, judging by the unflagging popularity of true crime stories presented in podcasts, documentaries, movies and books.

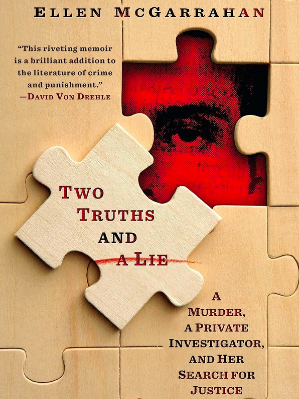

What sets Ellen McGarrahan’s just-published true crime book, Two Truths and a Lie, above so many others I’ve read is the moral gravity of her presence on the page and the hollow-voiced lyricism of her writing style.

McGarrahan earned both qualities the hard way. Long ago, when she was a young reporter for The Miami Herald, McGarrahan witnessed an execution gone wrong and she reported on the case and the executed man—a convicted murderer—by relying on, as she says, “the state’s version of events as the truth.” Two Truths and a Lie delves deep into McGarrahan’s more than two-decade-long odyssey to rectify that mistake.

McGarrahan earned both qualities the hard way. Long ago, when she was a young reporter for The Miami Herald, McGarrahan witnessed an execution gone wrong and she reported on the case and the executed man—a convicted murderer—by relying on, as she says, “the state’s version of events as the truth.” Two Truths and a Lie delves deep into McGarrahan’s more than two-decade-long odyssey to rectify that mistake.

Two Truths and A Lie opens in May of 1990 at a prison in Florida where McGarrahan has gathered with other reporters to witness the death by electrocution of Jesse Tafero for the murder of two police officers at a Florida rest stop in 1976. McGarrahan volunteered to be there because she wanted to prove herself. She was then the only woman in the Herald‘s state capital bureau and she was young. “Five years earlier I’d been deconstructing The Executioner’s Song in literature class at Yale,” she writes.

But nothing McGarrahan read could have prepared her for the grotesque reality of the execution that followed. Because of an electrical malfunction, Tafero’s head caught on fire. Months afterwards, a reporter friend advises the shaken McGarrahan to “Go see another one. … That’ll get it out of your mind.”

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))