One of the best features of Black History Month (and all celebrations of underappreciated cultures, for that matter) is the (re)surfacing of forgotten or unknown talents. This week’s picks salute a range of folks working the margins.

Edward Owens

Through Feb. 28

SFMOMA online

Edward Owens was a teenage prodigy whose output encompassed films, paintings and collages. He was enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago in the mid-1960s when, fatefully, Gregory Markopoulos joined the faculty. The pioneering experimental filmmaker discovered and influenced Owens’ work, and encouraged his Black gay student to head east in 1966. Imagine being welcomed into New York avant-garde circles as a gifted 17-year-old.

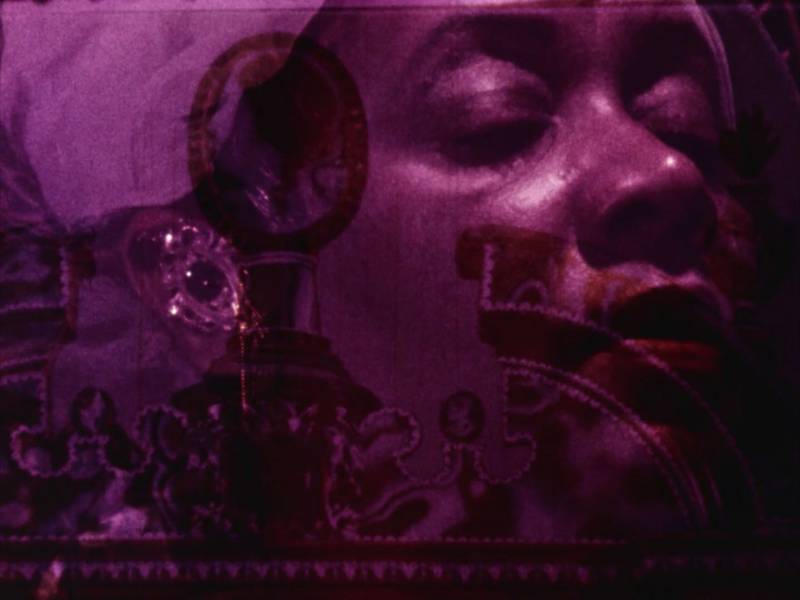

For the first monthlong installment of the three-part exhibition Assembly of Images: On Histories of Race and Representation, SFMOMA and SF Cinematheque unearthed a pair of Owens’ rarely screened short films that he shot in Chicago. Dreamy and mesmerizing, the silent Private Imaginings and Narrative Facts (1966) imbues Black faces with glamour and longing; it was originally entitled Mildered Owens: Toward Fiction (after its central figure, the artist’s mother).

Remembrance: A Portrait Story (originally called No More Tomorrows, 1967) also features the imposing Mildered (with friends Irene Collins and Nettie Thomas) and likewise suggests the gulf between reality and dreams. Owens wrote, “The music is by Marilyn Monroe singing ‘Running Wild’ from Some Like It Hot, because it’s a film portrait of Nettie Thomas. She did floors in white women’s homes, like Black women did to support their families in the olden days. My mother is sitting in a wicker chair with an ostrich feather boa, a grey worsted wool skirt, a silk belt. For her portrait, I used ‘All Cried Out’ by Dusty Springfield…”