Consider this: Of the violent deaths of unarmed Black folks at the hands of policemen and white vigilantes, a great many now occur in the North, rather than the South. Eric Garner was killed in New York City. George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Philando Castile was killed outside St. Paul, Minnesota. Mike Brown was shot in Ferguson, Missouri. Tamir Rice was gunned down in Cleveland, Ohio. Stephon Clark was killed in Sacramento, California. Freddy Gray was killed in Baltimore, Maryland.

The most segregated school systems are no longer in the South—instead, the most segregated school system in the United States is in a city many have long held up as a beacon of diversity and liberalism: New York City.

And while the American public imagination remembers the murders of Emmett Till and George Stinney by white supremacy in the South, the North was also an extremely unsafe place for Black Americans of that time as well. The post-World War I migration of Black folks North was followed by violence levied at the new Black arrivals by white Northerners. “So much blood flowed in America’s streets that year that James Weldon Johnson, field secretary of the NAACP dubbed it the ‘Red Summer’ writes Blow of the 1919 Chicago white uprising against the Black citizens of the region. “In ten months, an estimated 250 people were killed—including nearly 100 who were lynched.”

Weaving together deeply thought out analysis and in-depth sociological and historical research, Blow details how, as Black folks migrated North, “white people in Chicago found a way to formalize and ensure segregation: restrictive covenants” that made Black people unable to lease, buy, or even use property in certain areas of the city. The result? “By 1939, an estimated 80 percent of all Chicago’s land area was covered by these covenants,” Blow writes. Black Americans in the North suffered racial violence and reductions of rights codified by law—just like Black Americans in the South, but often without the support of extended family and community back home.

Blow connects the dots between moments of social advancement for Black Americans and the accompanying white backlash:

“Whenever Black people make progress, white people feel threatened and respond forcefully. Emancipation and the Civil War gave rise to the KKK, which formed just months after the war ended. The Supreme Court’s decision in Brown vs. Board of Education striking down racial segregation in schools gave rise to the white supremacist Citizen’s Councils. The election of the first Black president gave rise to the Tea Party, which was formed soon after Barack Obama was sworn in.”

As he discusses the rise of anti-Black violence and the need for safe spaces for Black folks, Blow draws from personal experience, detailing the moment his college student son was held at gunpoint on his Yale campus; how that moment echoed his own experience of being unjustly held at gunpoint by white police officers while in college himself. “He said he could make us lie down in the middle of the road and shoot us in the back of the head, and no one would say anything about it,” Blow writes.

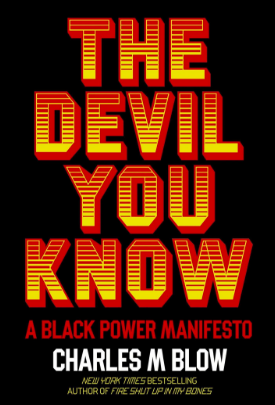

But throughout the book, Blow grounds his ideas in this central question: “What could and should Black people do to acquire and maintain the economic and political power—for the many, not just for the few—that the Great Migration failed to secure?”

Blow pays special attention to the role of elders in the community as he discusses how the original Great Migration caused a “loss of generational connectedness as an entire young generation left and the South became more of aged society,” adversely affecting both young people and the elders. Here, Blow crafts an homage to the elders in the Black community—from the great-uncle who babysat him to the importance of the example of elders like the 100 year-old Tim Black of Chicago who mentored a young Barack Obama newly arrived to Chicago.

It is also important to note the space Blow gives here to Black women social justice leaders who are often ignored, spending time with the mothers of the murdered black children—Samaria Rice, Sybrina Fulton; honoring the work of the great Shirley Chisolm; honoring the work Stacey Abrams. Indeed Abrams’ work, like Belafonte’s call to action, is an impetus of sorts for Blow’s book. “Georgia became the model for how Black people can potentially experience true power in this country and alter the political landscape,” writes Blow in his introduction.

The subject was Belafonte’s bailout of some student members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC.) Belafonte had raised $70,000 in bail money and called up his best friend Sidney Poitier to help him deliver the money. But it was not easy. Belafonte recalled how he and Poitier were chased by the Ku Klux Klan, whose members accosted them at the airport; Belafonte and Poitier had to take off speeding in a race for their lives.

The subject was Belafonte’s bailout of some student members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC.) Belafonte had raised $70,000 in bail money and called up his best friend Sidney Poitier to help him deliver the money. But it was not easy. Belafonte recalled how he and Poitier were chased by the Ku Klux Klan, whose members accosted them at the airport; Belafonte and Poitier had to take off speeding in a race for their lives.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))