California’s adoption of “The Golden State” as our official nickname in 1968 invoked the Gold Rush’s promise of riches and the gleaming achievement of the Golden Gate Bridge. For many, it also referred to the gold standard of best-in-nation schools and highways. California was No. 1 with a bullet, in the jargon of the pop charts of the day.

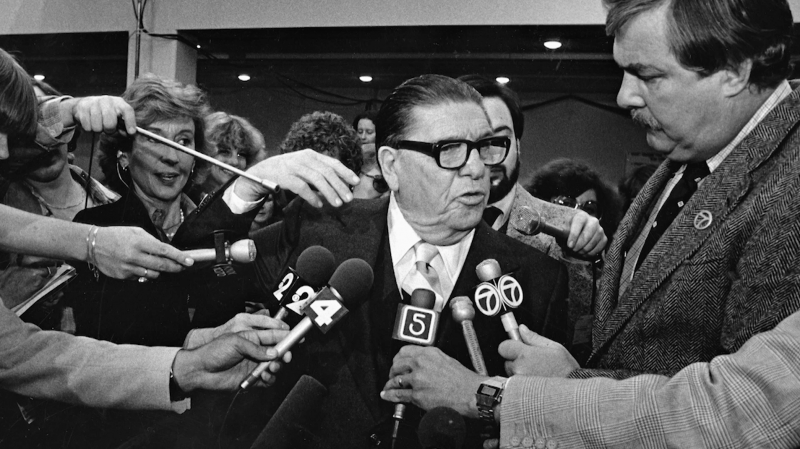

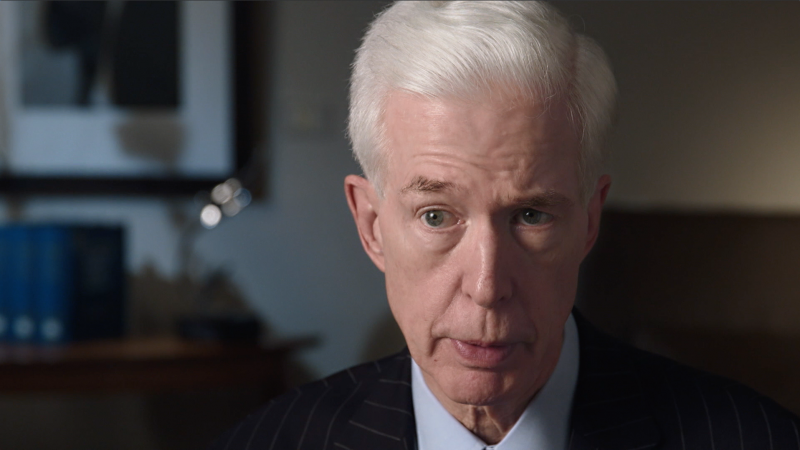

Fast forward 40 years to 2008, and the luster was gone. How we got there, and here, is recounted in Jason Cohn’s fascinating and insightful documentary, The First Angry Man. The film airs at 8pm tonight on KQED and 3pm Monday, Oct. 19 on KQED Plus.

“We were starting a family in Berkeley around the time when California was in financial free-fall, and the media was talking about California as a failed state,” Cohn recalls. “Meg Whitman was running for governor literally talking about the possibility of filing for bankruptcy. We couldn’t pay our bills, we were furloughing workers, schools had been cut and then cut more. It was clear to me that it wasn’t the kind of problem that could be solved by tightening our belts further.”

The schools were broken and infrastructure was falling apart. There was a ton of debate, with most everyone citing Prop. 13 as a central, unalterable factor.

“I felt like the conversation ended there,” Cohn says. “And everybody knew what they knew about Prop. 13, which was frankly not very much. It was this thing that had happened 30 years ago and it had cut property taxes. Depending on your ideological starting point, it was the reason you or your parents were able to keep their house or the reason California was in such dire financial circumstances.”

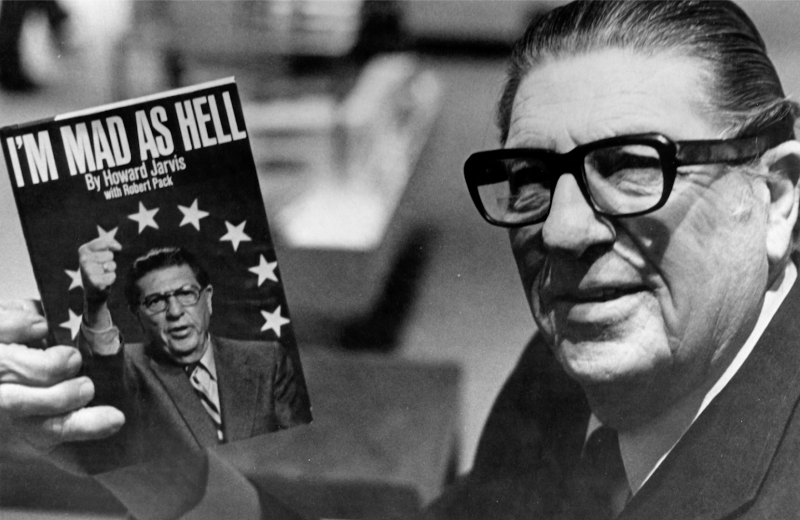

Curious about the dearth of actual information about Proposition 13 and its architect and champion, Cohn tracked down a copy of I’m Mad as Hell, the ghostwritten, self-mythologizing autobiography of Prop. 13 salesman Howard Jarvis. The proposition itself, approved by voters in 1978, amended the state constitution to cap—and effectively reduce—property taxes.

“I thought I would make a cheap kind of DIY [film], my wife [producer Camille Servan-Schrieber] and I do all of the work, do all the shooting and all the editing, just do it on the cheap, maybe on credit cards, just on the California problem,” Cohn explains. “Then I read how scholars view it, as a watershed moment that divided two completely different eras in terms of how people think about the role of government. It’s much bigger than taxes, it’s much bigger than California.”