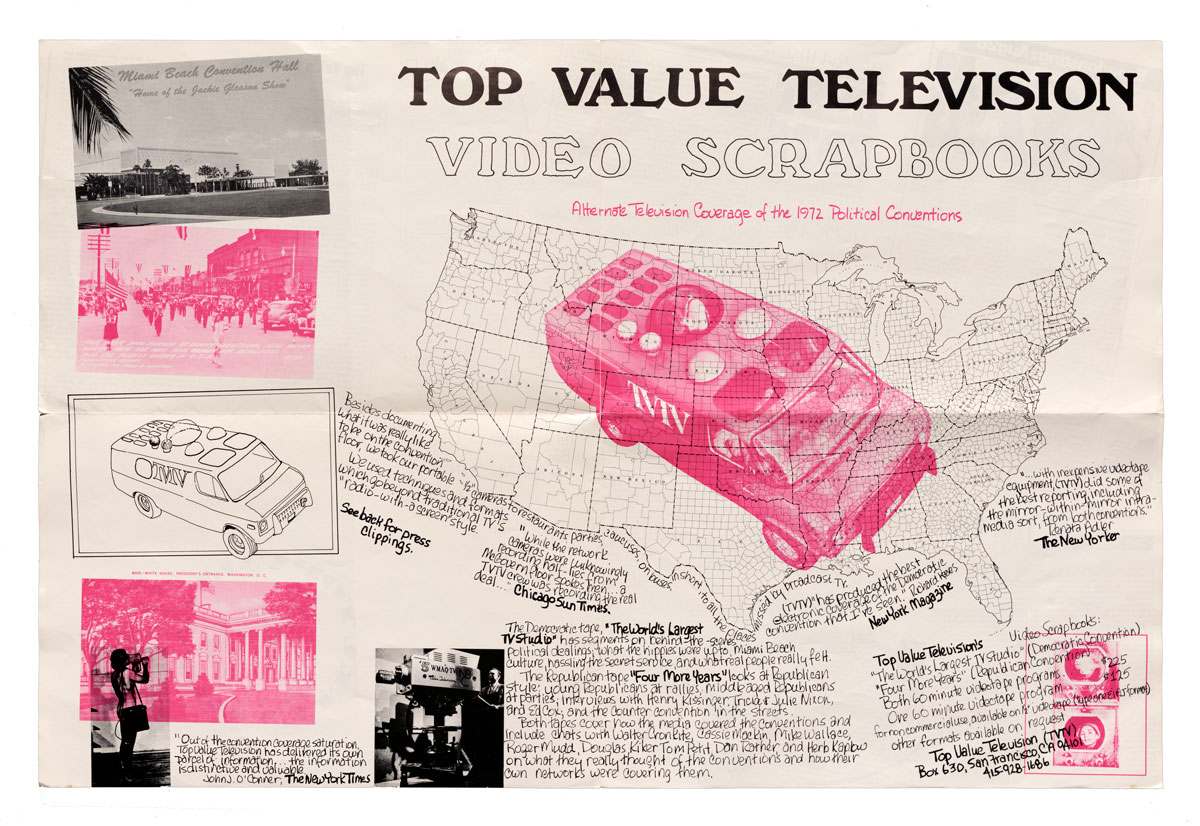

On the floor of a very different Democratic National Convention—this one in the Miami Convention Center, packed with maskless people, glad-handing everywhere—Top Value Television (TVTV) trained its video cameras on the in-between moments of a political spectacle. It was 1972, and a scrappy group of “video freaks” from San Francisco wanted to change the way television was made.

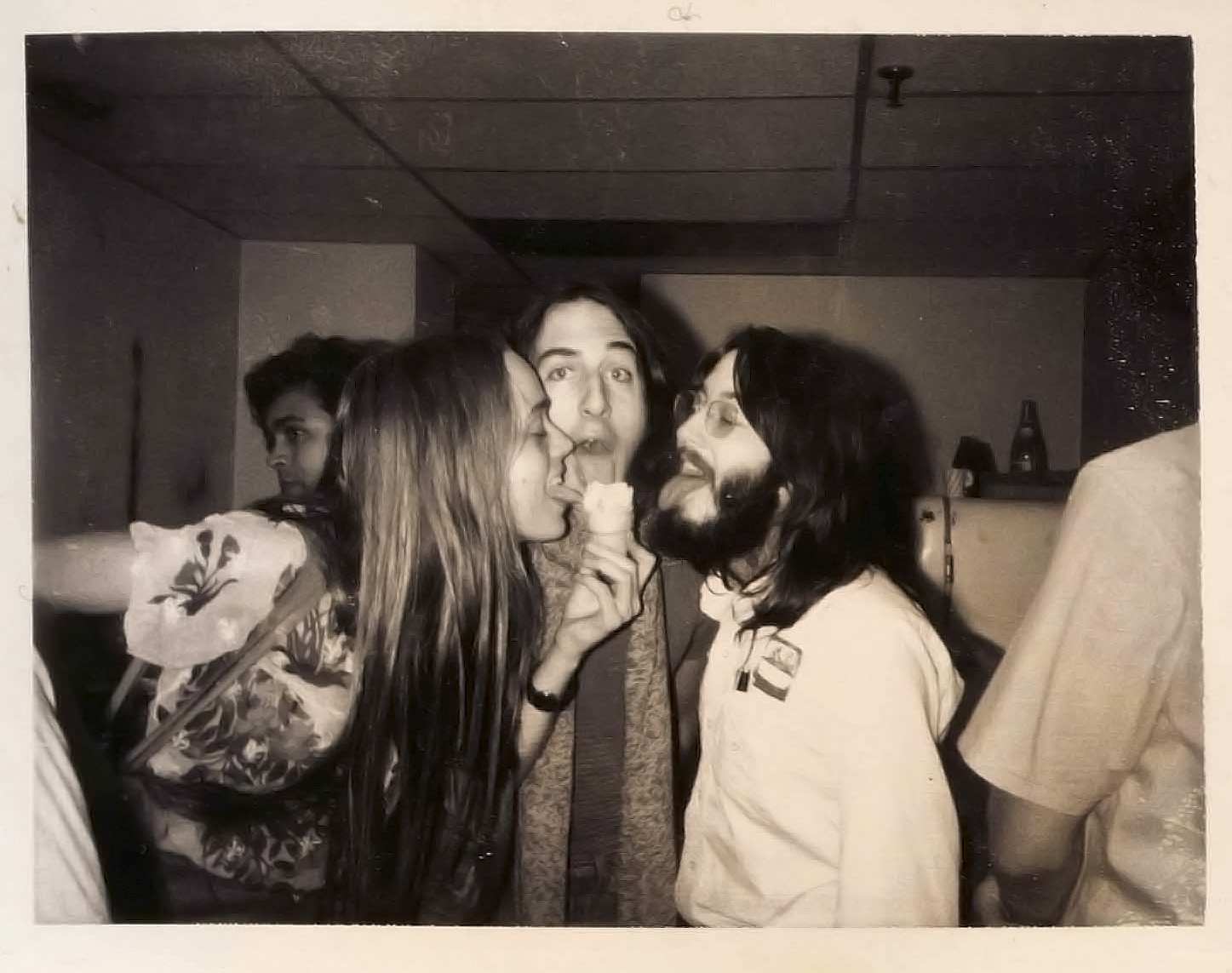

With 28 press passes in hand, the fledgling group shot hundreds of hours of footage at the DNC and RNC, which took place at the same venue just a month later. TVTV captured official votes and speeches, but also backroom discussions, Miami sightseeing, Newsweek interviewing them poolside, and, most notably, interactions with network television crews.

The official results of this new journalism endeavor were two hour-long, scrapbook-like documentaries, The World’s Largest TV Studio (about the DNC) and Four More Years (its RNC companion), initially screened on select cable channels and later available via video distribution services, or more recently, online.

But now, for the first time, the whole of that raw footage—in-between the in-between moments—will be available to the public at “Preserving Guerrilla Television” and soon, the Internet Archive, the result of a National Endowment for Humanities grant to the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. The newly digitized video captures what local archivist, filmmaker and educator Rick Prelinger calls “the flavor of TVTV’s work.” The raw footage contains extended “raps” by protesters and delegates, casual interviews with people who would become political heavyweights (a young John Lewis!), and a very real sense of Americans’ thoughts and concerns during a pivotal year.

A grant of $220,537 allowed BAMPFA to digitize 437 analog videos related to three TVTV projects: the two convention docs and Gerald Ford’s America, which shows the videomakers embedded in another spectacle, the first hundred days of Ford’s presidency after Nixon’s 1974 resignation. The grant also paid for scanning and photographing thousands of pages of paperwork, press clippings, scrapbooks and other TVTV ephemera.

It’s the culmination (in part) of a project that traces its roots back to a 2004 Ant Farm retrospective at BAMPFA, co-organized by then-video curator Steve Seid. (The Ant Farm and TVTV collectives shared members.) I specify “in part” because according to Michael Campos-Quinn, director of library special projects at BAMPFA’s Film Library and Study Center, this digitization project is “just the tip of the iceberg.” They actually have thousands of TVTV tapes, not to mention the work of other Bay Area video collectives.

“It’s so incredibly expensive to digitize the kind of tape that these are on,” Campos-Quinn explains. The videos are on half-inch open-reel tapes, one of the first portable videotape formats available to consumers in the late ’60s. With (relatively light) equipment like the Sony Portapak, guerrilla video groups could move nimbly through crowds, and produce media for a fraction of what the major networks spent covering the same event.