Visiting art shows used to be a regular part of my job. I’d see at least one show a week, sometimes more if I was feeling ambitious or visiting an area dense with galleries. But 70-some days into shelter in place, I’ve gotten so out of practice I can’t remember what I saw last. Was it Charlie Leese’s show for Bass & Reiner? Or the reopening of 500 Capp Street?

Nowadays, I don’t venture out much. Leaving the neighborhood has become the equivalent of a major expedition, not undertaken lightly and with about as much protective gear in tow.

Until this past Saturday, I’d almost forgotten how nice it is to have a reason to go somewhere—anywhere. The event in question was the opening of Curbside Exhibition at Catharine Clark Gallery, recent work by Sonoma artist Chester Arnold. The gallery’s first attempt at a socially distanced exhibition presents Arnold’s miniature oil-on-panel paintings behind a window facing the building’s lobby, a space shared with Brian Gross Fine Art.

It was a mixture of old-school opening and new-world rules. Buckets of sparkling water sat near dispensers of hand sanitizer; Clark greeted visitors in person, pointing to arrows marking out increments of six feet on the lobby floor. The gallery’s precautions to minimize risk to both staff and visitors were reassuring. (Everyone must wear masks and only three visitors are allowed in the lobby at a time, with staff remaining at a distance, behind a blocked doorway into the gallery proper.)

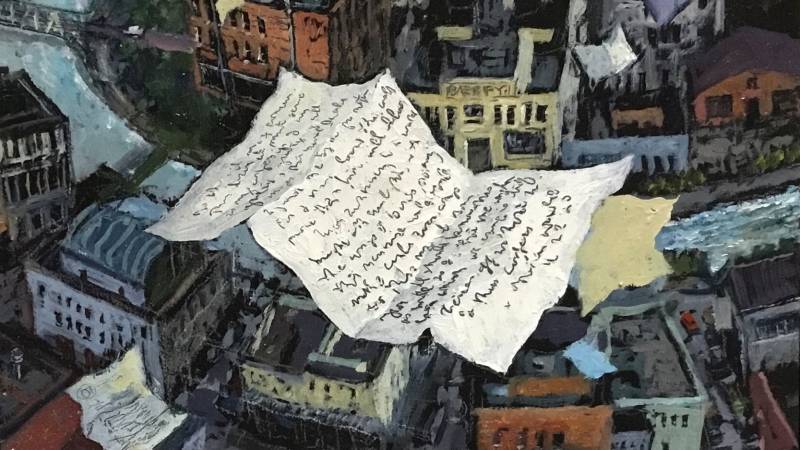

Arnold’s paintings are well suited to this approximation of a show. His small-scale works and fine brushwork necessitate up-close viewing, but seeing them through glass doesn’t diminish their effect. At the opening, an additional folding table was covered in works on paper, Arnold’s ongoing series of trompe-l’oeil folded letters. The whole experience felt a bit like an impromptu backroom show, mostly thanks to the personal attention of gallery staff and Clark herself.

I have to admit that seeing people—even just the top halves of their faces—was slightly overwhelming. I’ve become inept at small talk after months of conversing with only close friends and family. (When a casual acquaintance recently tried to chat with me at the farmers market, I blurted out “Have a great Sunday!” while pretty much running away.)