When Bruce Baillie died on April 10 at his Washington state home at the age of 88, the curtain also dropped on an influential yet seat-of-the-pants era in Bay Area avant-garde film.

A South Dakotan who studied in Minnesota, London and Yugoslavia, Baillie migrated here in the late ’50s and set about teaching himself cinematography and editing. In tandem with making films of uncommon beauty and grace, he founded Canyon Cinema (to screen and eventually distribute his and fellow artists’ films) and co-founded San Francisco Cinematheque.

“Immediately, I realized that making films and showing films must go hand in hand,” Baillie recalled in a 1989 conversation with experimental-film historian and critic Scott MacDonald, “so [in 1960] I got a job at Safeway, took out a loan and bought a projector. We got an army surplus screen and hung it up real nice in the backyard of this house we were renting. Then we’d find whatever films we could, including our own little things that were in progress—‘we,’ there wasn’t really any we, just me for a while—and show them.”

Baillie’s films evince his unique eye and sensibility yet generously allow ample room for the viewer’s experience. Revisit Castro Street (1966), shot largely in Richmond and redolent with train whistles and train tracks, evoking both night dreams and daydreams of an America to be explored just out there. “For Baillie,” MacDonald wrote, “the filmstrip is a space where the physical world around him and the spiritual world within him can intersect.”

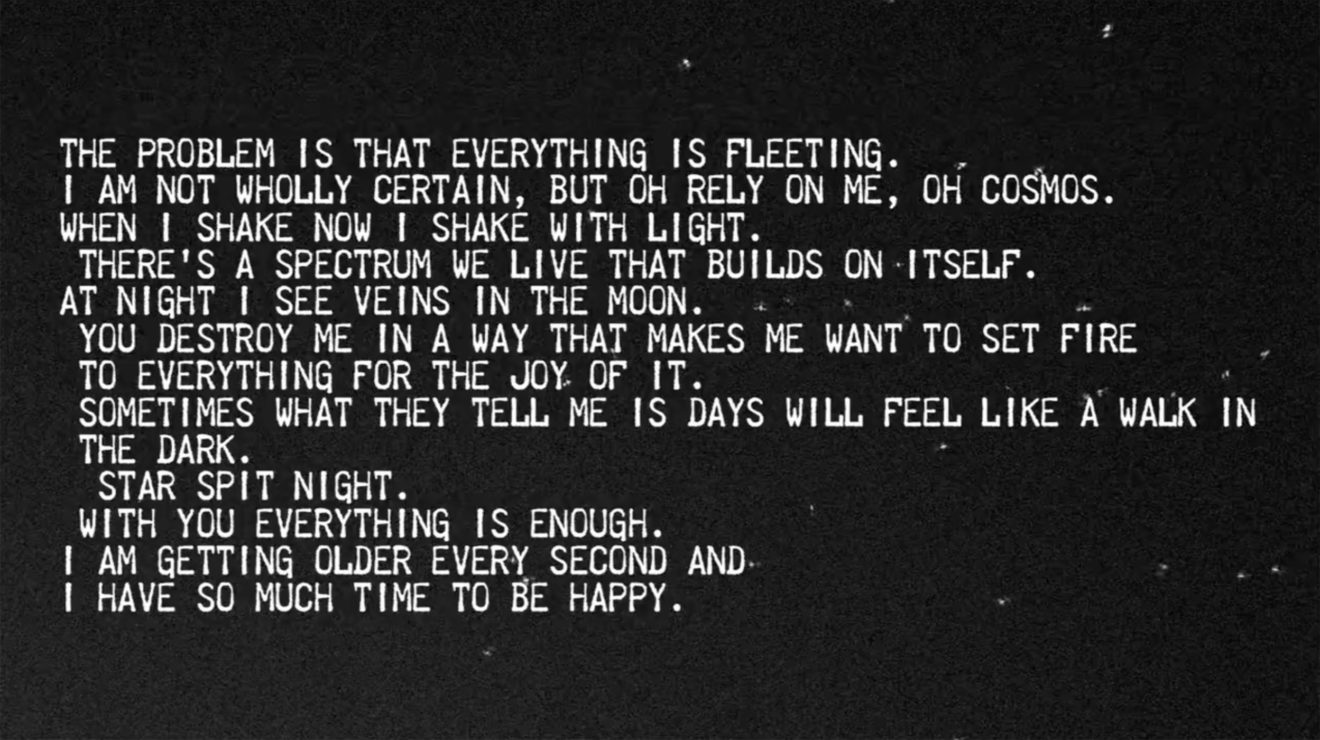

SF Cinematheque, for its part, continues to champion the handmade films of avant-garde artists, and is one of several local institutions streaming new and recent work for free while theater spaces are shuttered. The short-film compilation certainty is becoming our nemesis, which screened in conjunction with the Orlando exhibition curated by Tilda Swinton at McEvoy Foundation for the Arts until shelter-in-place orders went into effect, has moved online through May 2. From the morphing nude portraits of Alice Anne Parker’s Riverbody (1970) to Karly Stark’s onscreen pondering of the problem is that everything is fleeting (2015), the program embraces flux and fluidity—which makes it even more on point than curator Steve Polta could have imagined.