Since the arrival of the very first FDA-approved birth control pill in 1960, the burden of avoiding unwanted pregnancy has fallen almost entirely on the shoulders of women. In the United States in 2014, over 13 million women were using some form of hormonal birth control, versus 5 million condom users.

The right to access the pill was hard-fought (between 1965 and 1972, only married couples had permission to use it) and sparked a wave of newfound liberation for women once it was available to all. All these years later, there is a leftover sense—exacerbated by increasingly draconian restrictions on women’s reproductive healthcare—that women should be grateful to have access to birth control at all.

And since we’re so busy desperately hanging onto whatever bodily autonomy we can grasp, we rarely stop to ask why the onus of birth control is, outside of condoms and vasectomies, entirely on us. This despite the plethora of side effects (well-documented since the 1970 Senate hearings about pill safety) and physical trauma that we suffer in the process of using it.

As modern inequality goes, the division of responsibility between men and women when it comes to contraception is woefully under-examined. A trial for injectable birth control for men was halted in 2016 because subjects complained of side effects like muscle aches, acne and mood changes—all things women routinely abide with all forms of hormonal contraception. The abandonment of the study constituted a major disappointment for millions of women, especially given how long it took to even get a trial for men at all.

At the time, one researcher named Allan Pacey told the BBC that, “Unfortunately, so far, there has been very little pharmaceutical company interest in bringing a male contraceptive pill to the market, for reasons that I don’t fully understand but I suspect are more down to business than science.”

As Bader’s tweet proved, many men seem to have no idea of the physical, mental and financial strain that contraception routinely places on women. Just months ago, one male acquaintance even told me that birth control was mostly designed for women because it’s “easier for women’s bodies to deal with.” When I pushed back, he couldn’t explain how or why he believed this.

Truthfully, that misconception is not entirely his fault either. Women’s birth control burdens are grossly under-acknowledged, under-discussed and under-depicted in American pop culture. And while we have seen increasingly frank and realistic depictions of abortion on TV in recent years—thanks to shows like Shrill, Dear White People, Girls, GLOW, Scandal and Grey’s Anatomy—women’s contraceptive issues remain pretty much out of the picture.

Granted, Master of None‘s premiere did feature a magnificently awkward first-date Plan B purchase, and Shrill brilliantly depicted the high cost of morning-after pills (main character Annie always paid for them, not her boyfriend). But emergency contraception is no reflection of what women most regularly put up with.

Evaluating passing mentions of women’s birth control on TV, they tend to either remind women how lucky we are to have access to it (like the episode of Mad Men when Joan tells Peggy about a medication with a side effect that acts like the pill), or they gloss over side effects completely. In a 2012 episode of The Mindy Project, for example, when a college student tells Dr. Lahiri, “I heard that birth control makes you fat and cranky,” the doc simply quips back, “So does pregnancy.”

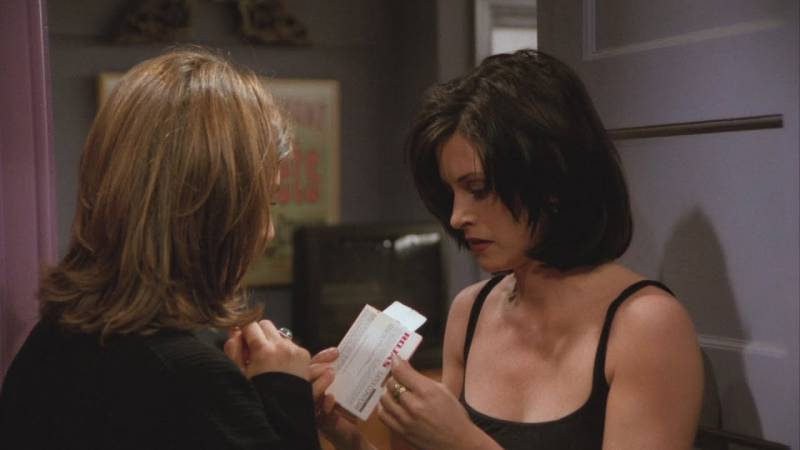

Truth be told, television has been doing a terrible job of reflecting women’s reproductive realities for decades. Teens watching sitcoms from the ’90s, for example, might be left with the impression that women’s contraception of choice back then was the diaphragm. Sex and the City, Friends, Felicity and Seinfeld all had diaphragm storylines at a time when less than 1% of American women actually used them.

And while Seinfeld‘s “sponge-worthy” episode remains one of the series’ funniest, even in 1995 it seemed like an odd choice for the thoroughly modern Elaine Benes. “Each episode, even the Sex and the City episode,” notes Vice journalist Kaleigh Rogers, “was written by a man who perhaps just didn’t have as keen of an awareness that diaphragms weren’t really a thing any more.”

And therein lies the problem. There still aren’t enough female voices in writers’ rooms or on TV, and the ones that are there aren’t, for the most part, concerning themselves with this topic. The fact that Shrill—an exception to the rule—managed to cause a full-blown internet panic with its revelation that emergency contraception is “only dosed for women 175 pounds and under” speaks volumes about TV characters’ need to be having this conversation.