My niece, Talyah, walked ahead of me in white sunglasses and AirPods, a 17-year old black girl with the edges of her hair laid to perfection, telling me about the process of perfecting them. She wasn’t even really tripping off of Wettfest in Stockton—car shows aren’t her thing. But when she looked through the tire smoke rising from the “donut pit,” and witnessed a dirty–Sprite-colored Chevy Silverado SS getting sideways, she turned back to me, pointed, and said, “I’ve been to car shows, but none of them had this!”

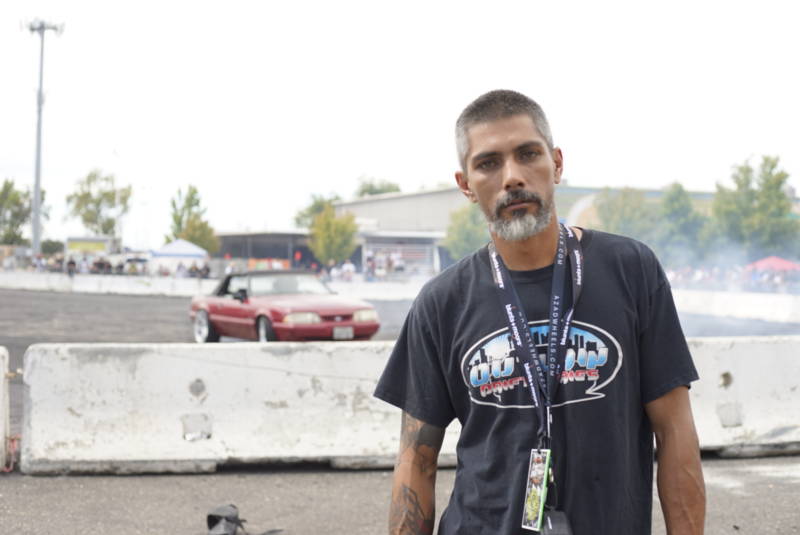

She wedged herself into the crowd to get a front-row view at the edge of the barricade, where we watched cars for a few hours in the donut pit, or donut box, hosted at the San Joaquin Fairgrounds on a square of concrete no bigger than a football field just made for people to pull up and swing donuts.

I could hardly believe my eyes. Meanwhile, at the start of September, numerous law enforcement agencies all around the Bay Area mobilized to crack down on sideshows. This past weekend, the Oakland Police Department released yet another notice that they’d patrol certain intersections, and join with other outfits from around the region to quell illegal sideshow activities in Oakland.

I’ve written two pieces about sideshows, one on how guerilla sideshows exemplify how wasteful we are, both as officers and citizens, and one raising the possibility of making sideshows legal.

I was just pipe dreaming until I heard the roar of an engine this past Sunday in Stockton, where cars were getting sideways in the donut pit. Legally.

Sideshows are an impromptu car show, in which drivers and spectators commandeer an intersection or highway in order to burn out, swing donuts, spin Figure-8s and more. They can attract hundreds of spectators, and they’ve been happening here since at least the 1980s. The cat-and-mouse dance between local authorities and sideshow goers has been going on just as long.

While this aspect of car culture is deeply intertwined with Oakland culture—and the culture of Northern California as a whole—it’s also somewhat dangerous, can become very chaotic, and on the streets, it’s illegal.

Which made the event in Stockton a possible blueprint for a way to do it legally. Attendees, like my niece, paid $20 to enter Wettfest, a family-friendly, annual car show thrown by DJ Tri Tip, Mudville Clothing Co. and Mike Alvaro. There were low-riders, hydraulic hopping competitions, big motorcycles, American-made candy-painted muscle cars, overpriced barbecue plates and Mexican food. There was even a kid’s zone with an astro jump, kiddie pool, the whole nine.

If you wanted to swing donuts, you had to pay $100. That’s what San Jose native Chris Coca did. I caught him and his 1997 BMW 328i (with the Louis Vuitton pattern on the interior door panel) while we waited in line with what I’m told was nearly 100 other cars. Gearing up for his second trip to the donut pit, he told me he pulled up early that morning in anticipation. After all, this is his catharsis.