When Adrian Rosenfeld Gallery arrived at Minnesota Street Project’s 1150 25th Street location (down the street and up the hill from the main gallery building), the first thing I heard was, “You have to check out the library.” Push open the gallery’s large door and you’ll see not white walls, but floor-to-ceiling thick walnut shelves holding thousands of art books. And often, set invitingly before them: a plump leather couch.

So despite its potential intimidation factor (blue chip work, collaborations with fancy international galleries, the aforementioned giant door), Adrian Rosenfeld Gallery is inviting, usually well worth a visit, and currently even more so.

Tadaaki Kuwayama and Rakuko Naito, an exhibition of husband-and-wife artists organized in collaboration with the Los Angeles gallery Nonaka-Hill, spans six decades of work. Trained as Nihonga painters (traditional Japanese figure painting), Kuwayama and Naito moved from Tokyo to New York in 1958, where they quickly shed their formal training and entered the emerging minimalist scene.

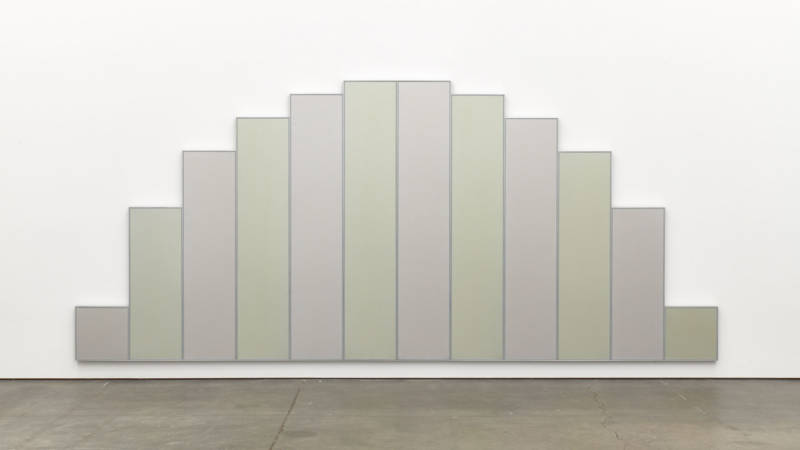

Rubbing elbows with Donald Judd, Ad Reinhardt and Frank Stella, Kuwayama and Naito’s work shifted to color fields, hard-edged geometries and delicate aluminum frames. Their paintings from this period are eerily precise, the acrylic surfaces rendered without a single hint of brush bristles—let alone a human hand. Some of Kuwayama’s paintings even have an iridescent sheen, adding to their otherworldly aura.

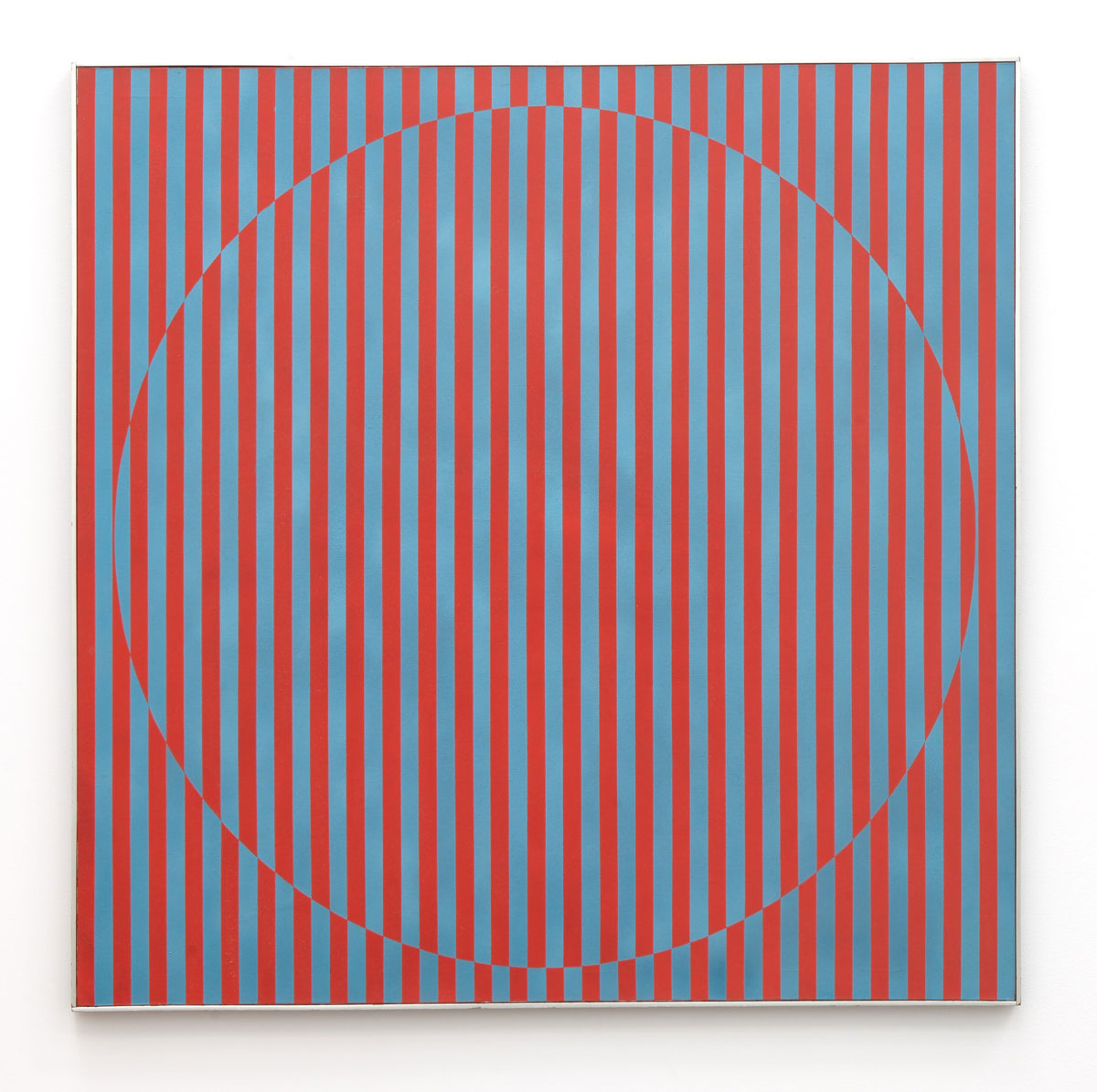

While Kuwayama’s pieces in the show, covering 1962 to 1991, demonstrate a singular dedication to form, Naito’s works within a similar time frame range across media, playing with dimensionality and illusion in the bounds of an often-square frame. Most recently, those frames provide space for the accumulation of delicate stuffs: twists of aluminum wire and coils of Japanese paper.