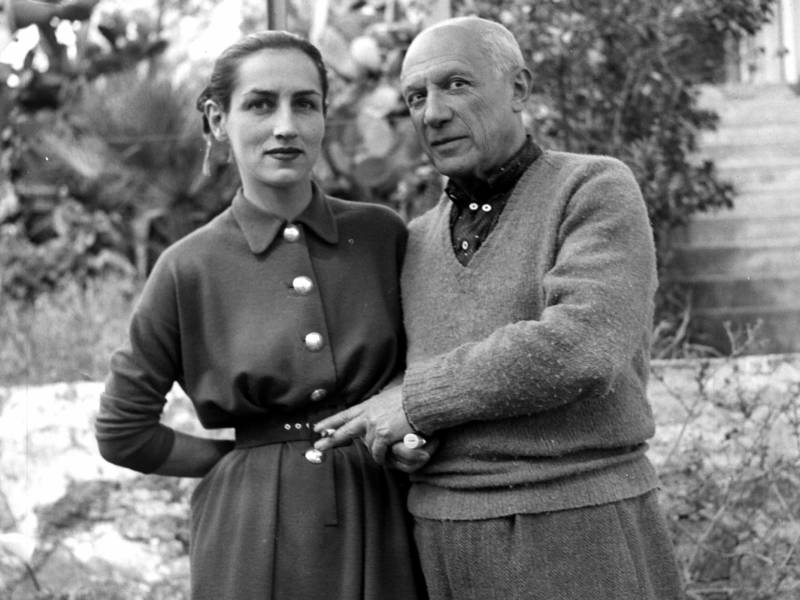

When the French painter and writer Françoise Gilot was 21, she met an older artist at a Paris restaurant. He invited her to visit his studio, and they quickly fell in love.

She defied her bourgeois family by moving in with him, and they remained together for 10 years. They raised two children, and she slowed her own career to be his muse, manager and support system. But this became untenable, and she left him, becoming a highly successful painter in her own right. As for the older artist — well, he was Pablo Picasso.

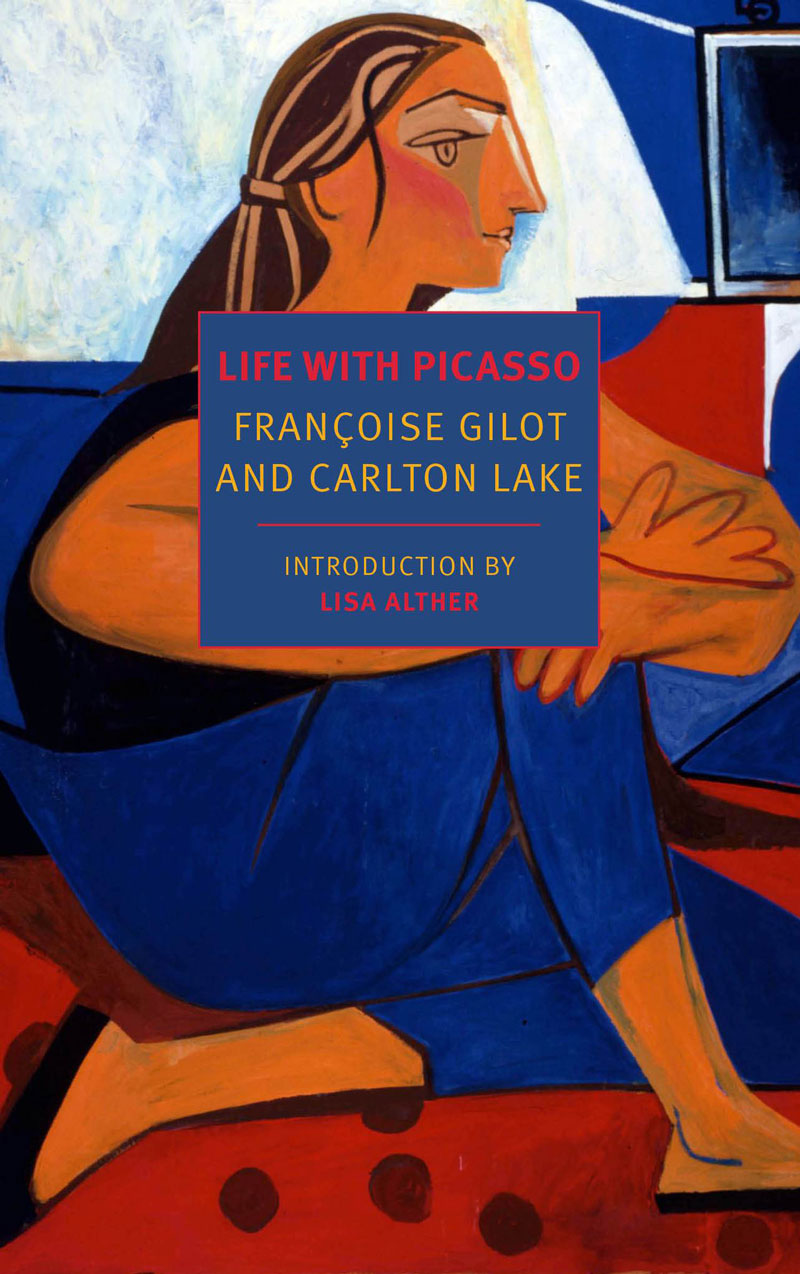

by Francoise Gilot, Carlton Lake and Lisa Alther. ( Random House Inc)

A decade after she and Picasso split, Gilot wrote a memoir of their time together, Life with Picasso, newly reissued by NYRB Classics. When it first came out, Picasso launched three lawsuits trying to block its publication — and 40 French intellectuals signed a manifesto asking that it be banned. The novelist Lisa Alther writes in her introduction to the new edition that these intellectuals “evidently found it acceptable for Picasso to have used Gilot’s likeness in hundreds of his artworks — but scandalous if she portrayed him in hers.” Thankfully, the challenges to Life with Picasso failed. Today, it stands as both an invaluable work of art history and a revealing precursor to the literature of #MeToo.

I have to admit to a certain temptation to read Life with Picasso exclusively as the latter. In Gilot’s telling, which is without fail warm and empathic, Picasso emerges as domineering, sexist, and borderline abusive. Multiple times in the narrative, he prevents Gilot from seeking medical care. He tells her frequently that “there are only two kinds of women — goddesses and doormats.” But Gilot is neither. She is never a victim or an ingénue. In Life with Picasso, she is a highly intelligent young artist to whom her former lover’s artwork is as intellectually exciting as their relationship was destructive.

Several of the best novels that have thus far emerged from the #MeToo movement, or been linked to it, have placed serious emphasis on their female protagonists’ intelligence or creativity as a source of agency, self-respect and liberation. Lisa Halliday’s Asymmetry and Susan Choi’s Trust Exercise excel on that front. Even the hapless protagonist of Erin Somers’ Stay Up with Hugo Best out-talks the late-night host with whom she becomes entangled. Life with Picasso prefigures these books. Throughout the memoir, Gilot takes control through her artistic intelligence. She describes Picasso’s methods and compares him to his contemporaries, filtering their work through her own exacting critical eye.

Gilot is exceptionally good at describing art. Often, she breaks an artwork into its essentials, as with a Picasso portrait that “had its planes brought over from the profile onto the front view, in blue and the black-gray-white gamut with ochre that is one of Pablo’s typical combinations.” But periodically she moves into full lyricism, as when she visits Giacometti’s studio:

“One gets the feeling of life or movement because of the exceptional acuity of Giacometti’s sense of proportion. He makes us feel that his people are in motion, not by imitating any kind of gesture, but by the proportion himself and by the elongation of the material.”

At no point does she mention what Picasso thought of Giacometti’s work. It’s Gilot’s ideas that matter.