Somewhere along the way, A Tribe Called Quest became the patron saints of ’90s hip-hop—a decade during which hundreds of rappers pushed boundaries, developed new sounds and honed the art form. Since Tribe first broke up in 1999, there’s been a documentary, dozens of magazine profiles, a new album, multiple reunion tours, late-night TV performances and T-shirts in stores like Urban Outfitters.

This ubiquity is a little concerning—and I say that as someone who loves A Tribe Called Quest. I think about how Johnny Cash came to represent classic country, or Ray Charles classic soul, or Bob Marley reggae, and I think about the way icons can become dangerously adjacent to caricature. I think about the overlooked artists in this process, and how the notion of “greatness” spreads in our culture unquestioned: best-ever lists get essentially copy-and-pasted, playlists fall back on the same hits and exaltation begets more exaltation.

Luckily, both a recent book and an upcoming tribute show for A Tribe Called Quest reclaim the group from canonization, instead highlighting what made their work so deeply personal for generations of listeners.

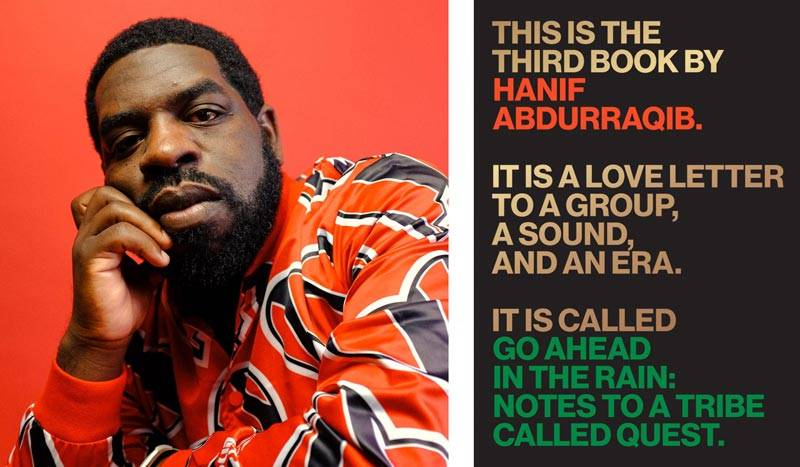

The book is Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to a Tribe Called Quest by Hanif Abdurraqib. Reading it is like listening to The Low End Theory with a good friend, and confiding in each other all the feelings and thoughts the music brings up. In a series of chapters moving chronologically through the group’s history, Abdurraqib doesn’t try to be all-encompassing or scholarly; with a love as personal as his, he writes from the heart, exemplified by open letters to each member of the group.

Abdurraqib’s passion for Tribe comes from a particular time and place, when fans obsessively studied liner notes and interviews. He takes the reader through a deep knowledge of other artists from the era, of specific samples, of exact turning points in the group’s career. He understands that Tribe was great, but so was Mobb Deep. For anyone who’s listened to Tribe so many times that their music feels commonplace, part of the air, invisible, Abdurraqib brings it back to vivid presence through context and beautiful, poetic description.