In the race for Alabama’s U.S. Senate seat last December, 98 percent of Black women voted for Doug Jones, effectively blocking Roy Moore, an evangelical candidate accused of sexually assaulting and pursuing several teenage girls, from taking office. Soon after the exit polls were released, prominent figures like Tom Perez, the chair of the Democratic National Committee, tweeted that black women had saved the day.

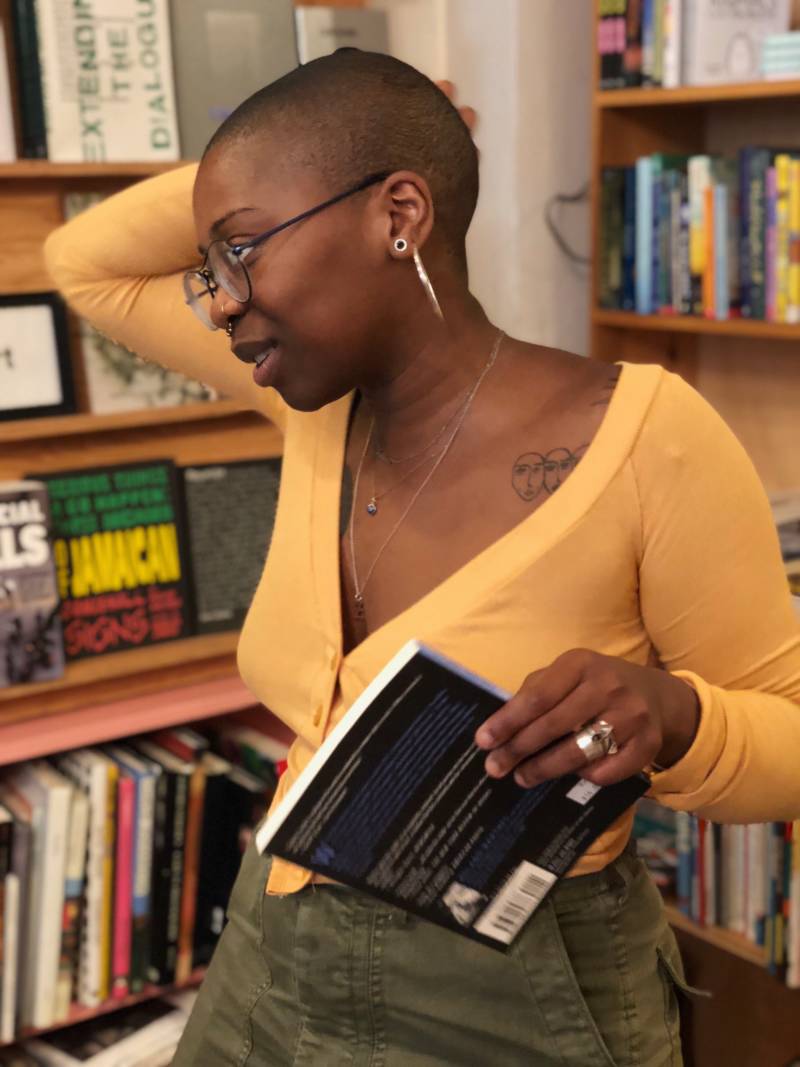

When I ask Zoé Samudzi how that makes her feel, she sighs.

“I hate that phrase, ‘black women will save us,’ because we’re really just trying to save ourselves,” she begins. “And in saving ourselves, we incidentally help others. That phrase is a really violent way of turning us into these political mules, into these super-mammies. Meanwhile, the politics that we have are only really applauded and appreciated when they serve white people.”

Samudzi, a 25-year-old medical sociology doctoral student at the University of California San Francisco, is the co-author of the recently released book of essays As Black as Resistance. She’s also a rising star for her scholarship on black feminism and critical race theory. With nearly 50,000 followers on Twitter, Samudzi’s work and ideas have galvanized a diverse, millennial audience within and outside of academia. In As Black as Resistance, she and her co-author, William C. Anderson, explore a range of themes centering on blackness in America, including anarchism, colonial land and legacy, black radicalism, racial capitalism and white supremacy. Throughout the book, the authors focus on how anti-blackness leads to structural racism, the liberation politics of black radical groups and the state and police surveillance of black communities.

Noticeably, Samudzi and Anderson do not dismiss the militant methods used by radical groups like the SNCC and Black Panthers, who rose to prominence in the 1960s, a time when white Americans terrorized black communities with lynchings and church bombings. In our conversation, Samudzi mentions some of the Black Panthers’ armed tactics. Originally dubbed the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, the Black Panthers were involved in many violent encounters with the police. Samudzi doesn’t dismiss these methods, positing that there are “multiple tools for racial liberation and self-determination that can be used, whether they are non-violent civil disobedience or armed struggle.” She believes that black people should be able to defend themselves in any means necessary against racial violence and points to Martin Luther King, Jr.