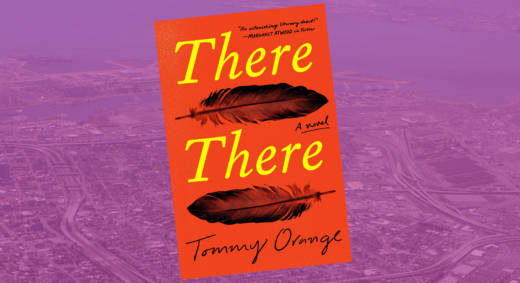

There There is Tommy Orange’s debut novel. It’s a book that feels like a city. Its chapters follow multiple generations of Native Americans who’ve made their way to Oakland; the characters’ storylines progress, at clipping speed, to one moment that will change all of them. There is a profound subtext to the novel—that of place and what it means to belong somewhere when you’ve arrived uprooted.

In the prologue, Orange writes, “We’ve been moving for a long time, but the land moves with you like memory… We came to know the downtown Oakland skyline better than we did any sacred mountain range, the redwoods in the Oakland hills better than any other deep wild forest.” Bold and ambitious, There There is a book that leaves the reader resonating with its language and depth long after one closes its cover. I talked to Tommy Orange about masks, erasure, Oakland and, of course, writing.

Where and how do you write?

I don’t know that I have any specific kind of “where” or “how” anymore. By this I mean, I don’t currently have a routine and haven’t for a little while, so it’s kind of a “whenever and however I can” situation. When I have had a routine, I usually include running as part of my writing process. I’ll try to run for an hour and, if I’m lucky, I’ll have anywhere between several to dozens of ideas toward writing or solutions to problems I have for whatever I’m working on.

Then I’ll work at a coffee shop with noise cancellation headphones on. There’s something about everything being busy around me without me having to hear any of it, always with music on, writing for as long as I can. On a good day I’ll get two thousand words in. If I’m more in revision mode, I don’t have particular goals in mind, just time at the computer.

At night, I work on the floor of my son’s room, prone, lying on my stomach with my elbows to prop me up. I’ve been writing this way for a long time. I’m not sure why. My favorite place to write is in a hotel room. There’s something about the cold quiet solitude of a hotel that’s really good for writing for me.

I love writing in hotels! It feels impersonal but clean—a perfect white room. As I was reading this beautiful, powerful work I kept thinking of one of your epigraphs. Javier Marías writes: “How can I not know today your face tomorrow, the face that is there already or is being forged beneath the face you show me or beneath the mask you are wearing, and which you will only show me when I am least expecting it?”

I came to the United States from Colombia with a perfect American accent. I used to have a British accent because my first English teacher did. Then I had an American teacher who “corrected” the accent. It always interested me—the desire to correct something that was obviously a mask. Masks can feel safe, but also somewhat sinister. There is a theme in this book of being seen but not observed, inexact racism and erasure. Where you thinking about these things when you picked this epigraph out?

One of my characters has fetal alcohol syndrome. You can see it on his face. He calls it the Drome. The Drome is a mask, and it’s the way people look but don’t look at him. The way people can’t look at him but he knows they know what they’re not looking at. This is the way it can feel being Native. People don’t want to talk about it. They want to look away. Pretend it isn’t there. There’s an insidious presence to that kind of absence. I like the way a mask can be more real than the person wearing it. Also he likes the rapper MF Doom, who too wears a mask.

You’ve done something gorgeous with the structure of this novel. At times I want to call it a braid, but other times it feels like a spider’s web, each strand resonating with and sending mild disturbances to what came before. In the book you write of a mother not allowing her children to kill spiders: “Spiders carry miles of web in their bodies, miles of story, miles of potential home and trap. She said that’s what we are. Home and trap.” I am so taken with this passage. I’ve thought about it on and off since reading it. Could you tell me about how you came about the structure of the book, and maybe talk a little about spiders?

I thought of the structure for this novel from the very outset, before I even started writing it. It came to me in a single moment. It was the strangest thing: I could see the whole thing at once. I was convinced of it enough to write into it for the next six years.

Of course, making it work and successfully braiding, or webbing, the thing was difficult. I knew I wanted it to be a novel and not a collection of stories calling itself a novel. I didn’t think of a web while writing it. That sort of came about of its own accord. Maybe like making an accidentally cohesive mosaic. Not that I wasn’t putting in the work to make it cohesive. When you work with complexity and chaos that you do your best to wield, sometimes unintended patterns emerge.

Regarding spiders, well, when I was researching, I came across this idea of miles of web in a spider’s body. There was just so much potential for metaphor there. And then, like one of the characters in the novel, I too pulled spider legs out of my own leg. It was crazy. There’s no explanation for it. I did a ton of research. Like my characters, I scoured the internet. When I asked my dad he told me it sounded like I got witched. I don’t know about any of that. What I did end up feeling was like I couldn’t not use it in the novel.

Oakland is very present in this book. You spent a lot of time observing the city and working it into this novel—and I wondered, what does Oakland look to you now that you no longer live there?

I think not living in Oakland helped, in ways, to see it better. Being away from Oakland has always made me miss it in a way that makes me want to write about it as a way of reconnecting. I think writing about Oakland while being away from it and missing it was essential to writing this book. We’ve been trying to move back but haven’t been able to afford it. We can now, thanks to this book, so hopefully we’ll be living there again this year. Nothing would make me happier.

Have the rising rents destroyed the place that was

Oakland is in no way destroyed in my mind. It’s different. But it’s always been changing. The loss of people who called it home for so long due to rising rent and gentrification for me is the biggest loss. People being forced out of their homes. Out of Oakland. The loss of these people is irretrievable. But there are still plenty of people who go way back in Oakland, still people keeping it strong, and a thriving art scene, and a sense of pride in place, in this being home. It helps that the Warriors just won.

![]()

Tommy Orange reads from his novel at Bookshop Santa Cruz on June 18, and at the Jewish Community Center in San Francisco on Tuesday June 19. More information here.

The Spine is a biweekly column. Catch us back here in two weeks.