Ah, Americanness. Today, a word so hard to define. A word that conjures images of a nation divided, of a broad and growing gulf between opposing visions of just what America is and should be. But viewed through Walker Evans’ lens, the eponymous exhibition at SFMOMA seems to say, America was once a united place, brought together by the charming features of small towns, misspelled placards, roadside advertising and cluttered window displays.

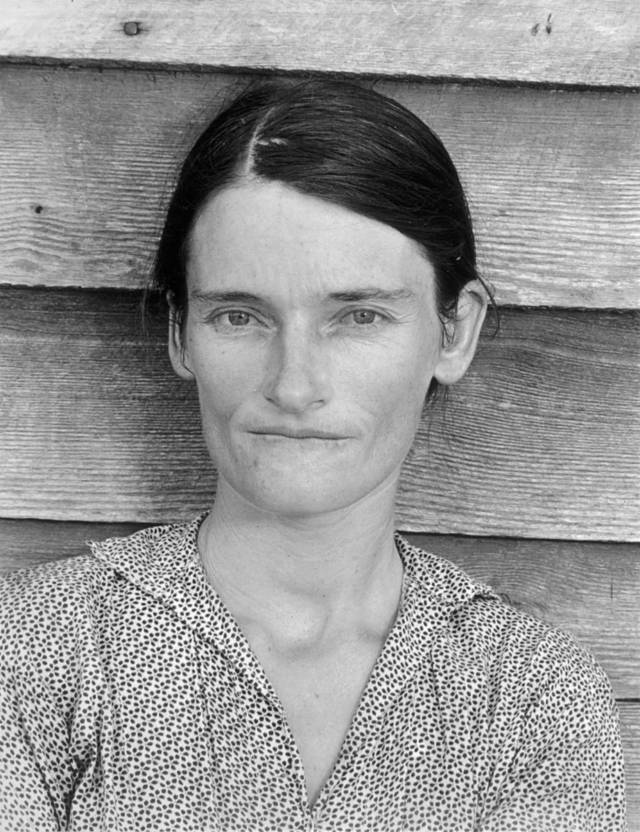

The problem, of course, is that America was never one united place. Evans himself captured this: One photograph from 1936 is titled Negroes’ Church, South Carolina while another from the same year is titled, simply, Wooden Church, South Carolina. The very premise of Evans’ work for the Farm Security Administration was to document — for those unable to witness it firsthand — the plight of poor American farmers in the heartland. Roy Stryker, head of the FSA’s Information Division, called it “introducing America to Americans.”

With approximately 400 objects on its exhibition checklist, SFMOMA’s Walker Evans retrospective spreads across both the Snøhetta and Botta sections of the museum’s third floor. Admittedly, it’s a lot to take in, even in an era when we can spend hours scrolling through Instagram, blinking past hundreds — if not thousands — of pictures a day.

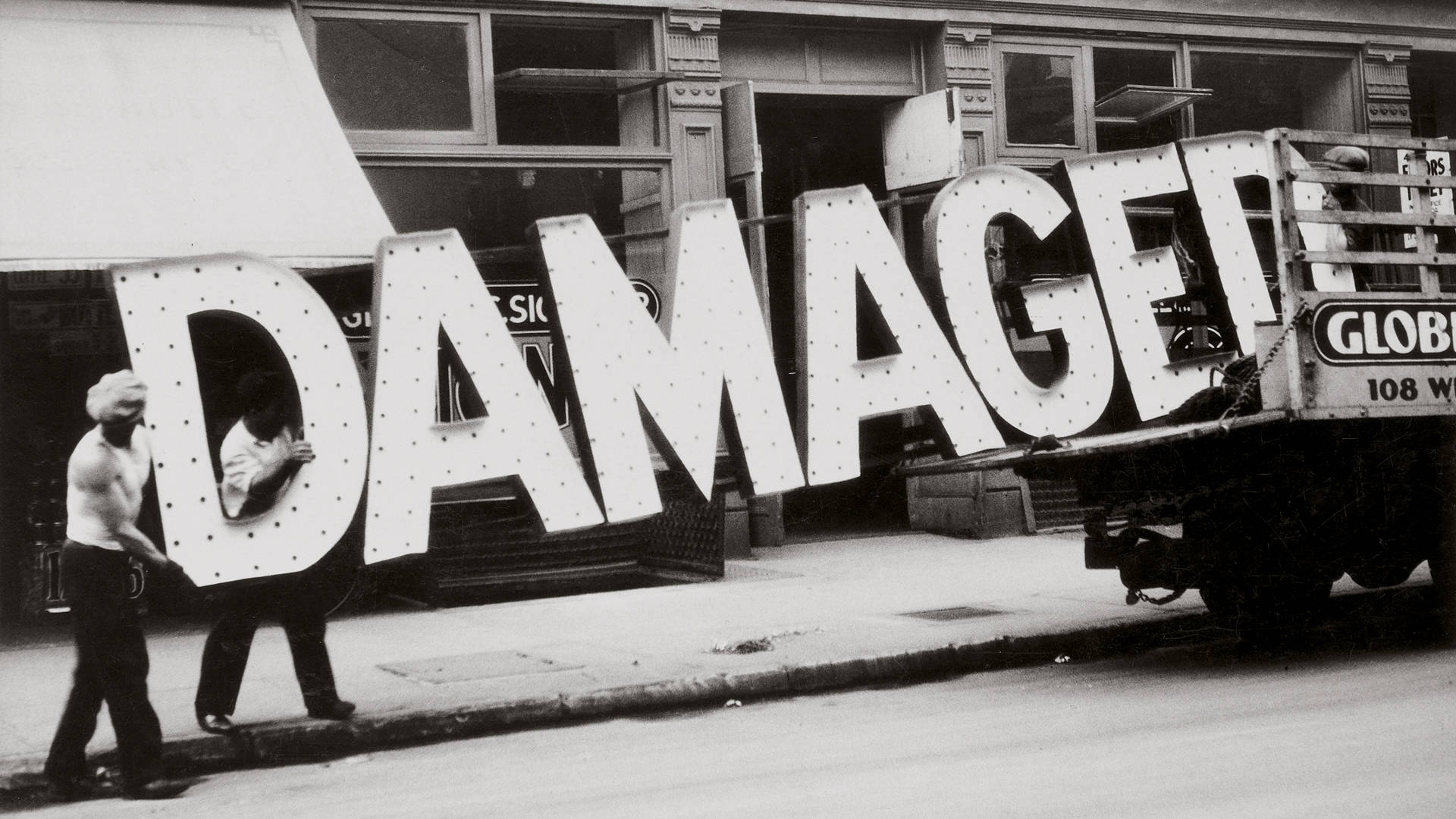

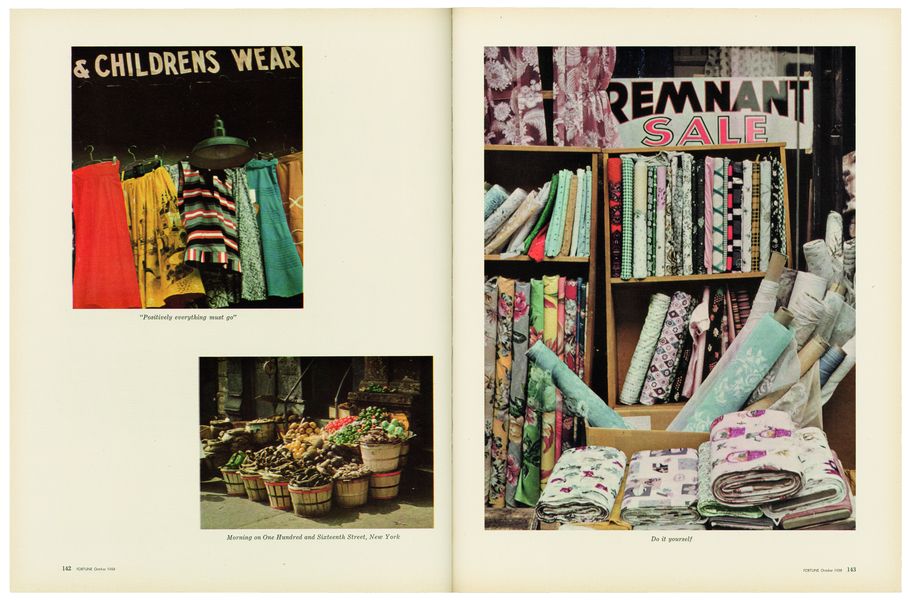

Walker Evans is not organized chronologically, but thematically, grouping works by subject matter across the photographer’s 50-year career. The first show organized by the museum’s new senior curator of photography, Clément Chéroux, makes an argument for the late, great photographer’s particular focus on both vernacular subject matter (main streets, storefronts, hand-lettered signs, ordinary people and utilitarian objects) and vernacular methods of capturing those images.

In terms of expanding knowledge of Evans’ oeuvre beyond his most famous image (his 1936 FSA photograph of Allie Mae Burroughs), Walker Evans provides multiple (too many?) examples of other bodies of work. See his early angular images of New York City and his street photography, along with secret-camera snaps of unassuming subway passengers. Previously unknown to me: his catalog-like pictures of various hand tools. And paintings! Did you know Walker Evans sometimes painted?

![Walker Evans, 'Untitled [Street scene],' 1950s.](https://ww2.kqed.org/arts/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/10/12-Untitled_1200.jpg)

Perhaps the most interesting sections demonstrate Evans’ preoccupation not with a spick-and-span version of Main Street America (though one such photograph was adapted into a 1942 government propaganda poster), but with the darker underbelly of American capitalism.