When Can began, the band had little experience with rock music. But you became a rock band.

We were bloody beginners altogether. Maybe except Jaki Liebezeit, the drummer. Jaki was quite experienced. He played one year with Chet Baker in Barcelona, and was a real jazz drummer. But the rest of Can was different. I was just nothing. I just studied with [composer Karlheinz] Stockhausen; I didn’t have any practical experience. I had some sort of weird ideas. [Michael] Karoli, the guitar player, was my pupil, and he started to study law. He had nothing in his hand too.

We were all bloody new beginners, and tried somehow to grow out of our soil. Irmin [Schmidt], he had some sort of experience being a conductor. But he was a beginner in playing in such a group. [Even] counting until four, he had really sort of big problems in the very beginning. [As did] every one of us.

What were Can’s main influences from the world of rock, as opposed to classical and avant-garde?

The influence, for me, of Beatles and Velvet Underground was most important. The Velvet Underground especially. They had something achieved which others didn’t achieve. Even Jimi Hendrix didn’t achieve [what they did]. One could have the opinion that this group is not able to play really properly right. They didn’t get the right rhythm, they couldn’t make a real tight rhythm. But the music was incredibly convincing.

This feeling made us encouraged to go on with rock music in general, instead of making avant-garde academic music. We liked to do something without notation. We didn’t want to read music off papers. We really tried to make instant compositions from the very beginning. This Can tradition actually [was] achieved very much when we played live.

What do you see as Can’s influence on German and European progressive music?

People of our generation, I think they were not influenced at all. When they attended Can concerts, they thought maybe it was exciting. But nobody of these people were ever thinking, “Hey man, this is something we should take as an

ideal, we should take as a way people follow up.” In Germany, actually, Can didn’t become such an image of being heroes.

But younger people who attended our concerts, [the] next younger generation, especially in England, they became addicted, actually, to the way of how Can made music. I found out in the last year, especially in Russia for example, [that] Can will be treated with young people sometimes [like] the Rolling Stones. The Russian people see a good way of making progressive music on their own without being forced to copy rock and roll.

How do you think Can has influenced the music of today?

Actually, I think they are not such a direct influence on these electronic people as Kraftwerk. In Germany the DJs and the young people, their fathers [were] not Can, it was Kraftwerk. Can actually was a real band, but the new music is not based on the idea of forming a band.

But when it comes, let’s say, of making a party or a live evening, making a big performance of nothing, then Can can become very important, because this was how Can was going on stage. Actually with an empty head, nothing pre-performed or nothing pre-whatever. We just went onstage, and who was throwing the first stone, we caught that and threw it back. And that was the beginning of the concert.

I think this music Can made had something to do with football or with sports. That means, you can’t really say in the next minute, where is that ball going to. A team which is playing with such a ball knows very well about those strategies. But actually you can’t say, by definition, when is the ball in this or this area. It’s the same with Can music. We know how to build up the whole thing, but the actual sound and the actual development of the thing was not foreseen.

In the studio too, each Can album was unpredictable.

It was like that. We knew making records, as other groups are doing, means pre-performing the whole thing, practicing songs and something like that, and then going to the studios and just perform[ing] and produc[ing] it. And after a short time, you are getting out of it again.

This was not our intention. We didn’t have anything on our mind. We just played together live in the studio as we would do it on stage, without audience.

Were there any albums you preferred more than others?

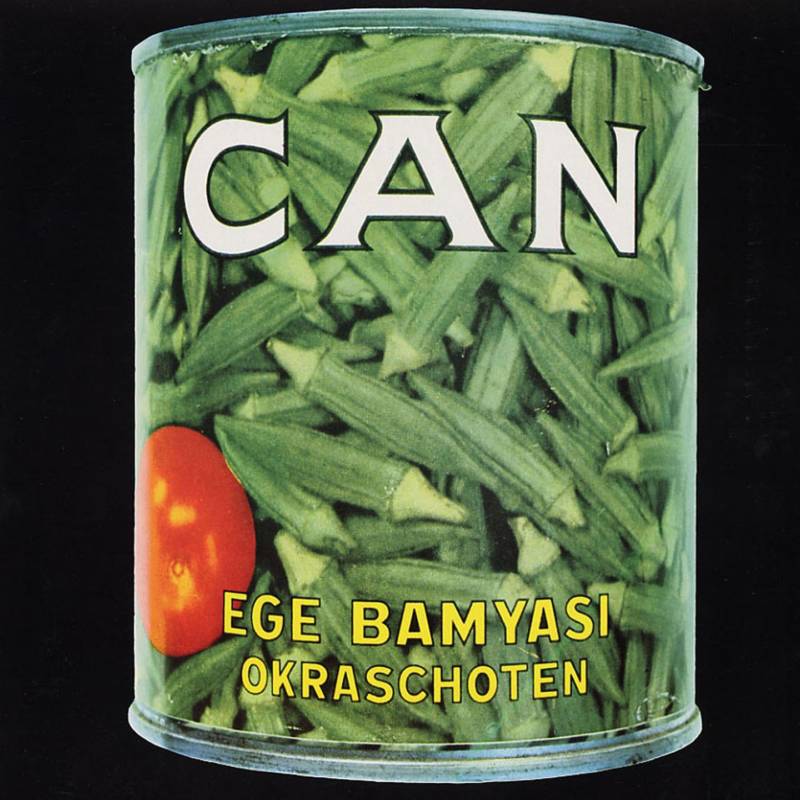

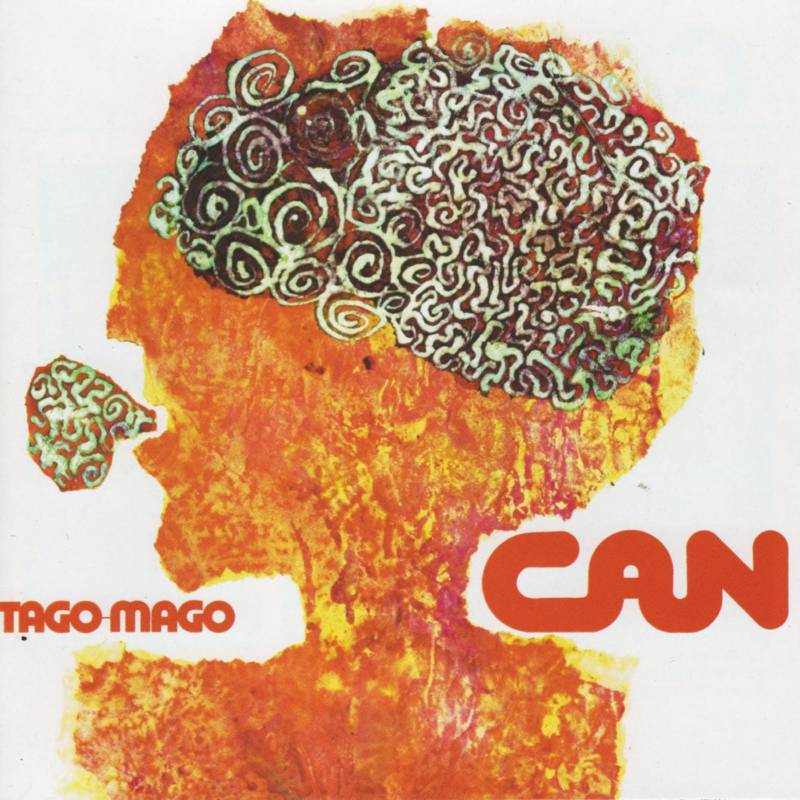

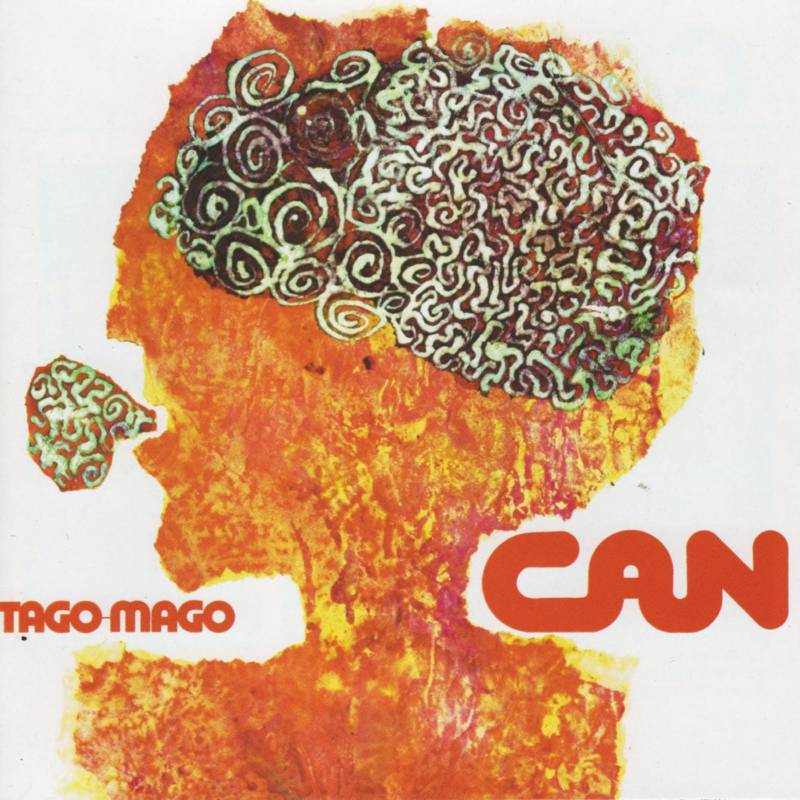

I regard the very first albums being the most important, as Can was most innocent at that time. If a group is new, young, and starting from the very beginning, actually you can’t do anything wrong. You do something wrong when you try to learn, and when you get older, getting experienced, this is when you can do mistakes and have some errors. It’s quite normal, I think, for every group. That’s the reason I really love Monster Movie, [1971’s] Tago Mago. Soundtracks [from 1970] is a great album.

When Can hooked up with Virgin Records in the mid-1970s after Damo Suzuki left, was there any sort of pressure to go commercial?

That was one of the reasons what made problems in the group. In the beginning, we were a real group, an entire group. That means we were recording straightaway on two tracks. Then we became successful, we had a hit in Germany, and we were able to afford a multi-track machine. From this moment on, you can say it was the beginning of the end of Can.

In such a group, everybody has to criticize the other one about what he’s doing wrong and so on. But when the multitrack machine came out, it was “I want to hear guitar, or I want to hear the bass, who has made this wrong?” [Musicians were] getting a little bit afraid, and said “Okay, okay, I do my part now and play it as good as I can, and the others shouldn’t be in there,” because it makes him nervous. This was the beginning, where the group suddenly was not such a strong group again. Even if they were more sophisticated about production.

I knew where the weak point of Can was. There [was] too much dealing just with themselves, and nothing which came from outside. So I looked out for radio and all these sort of devices, including telephone. That means you suddenly get information from outside, getting off from your routine, and getting fresh again from the very beginning. But in terms of becoming more commercial, maybe, the other members didn’t like this idea very much. That was why I got out and started on my own, towards the end of Can.

I wonder if you could compare the band as they were with Malcolm Mooney and as they were with Damo Suzuki.

With Malcolm Mooney we were very fresh. Malcolm was a great rhythm talent. He was a locomotive. That was the right singer [for] the very beginning. We were creating rhythms, but we were not very stable in doing that. That means someone who was pushing us into the rhythm, and giving us the feel that this is the right thing to do — this was Malcolm Mooney, and he got integrated very much into what all the other musicians did. He was the right singer at the right time.

When he left because of psychological reasons, Damo came in. The group was far more experienced by that time. Damo is not such a pusher. He is a different sort of singer, and therefore the group achieved such a stability. Damo fit perfectly into that.

The problem was, when Damo disappeared, Can was without a singer. Suddenly we felt a hole in our music. Michael was singing, but he is not…a guitar player actually should not sing, except like Jimi Hendrix or something like that. Actually a guitar player should play guitar. That was our problem. We tried out so many singers at that time, and nobody really fit again into this group. It was somehow Can’s fate, or tragedy, or whatever you can call that, that it happened like it happened.

It seems you could call Malcolm and Damo joining the group inspired accidents.

You can say, if you’re a religious person, they were given by god for starting something for mankind.

Does it come as a surprise to you or other people in Can to learn about the group’s cult following in the US?

Yes. You see, this following came up by the years. I always thought that if Can makes it, it will make it in America. I thought the way the rhythms were done, the way we played live, it was a hell of rhythmic impact. I thought that would fit far more into America than into Europe.

But in England, it was in [the] beginning accepted with greatest enthusiasm. Then the French people reacted on that very, very strong in the beginning of the ‘70s. But from America, we didn’t get really any reaction. We heard that we should come over and play, but somehow all this was so unstable. Nothing was really confirmed in such a way that we could say, “Okay, let’s do it, let’s go over.”

How have you drawn upon Can’s influence in your solo career?

When I started my solo career, I only could do that because Can was such a good time for learning everything you need to stand on your own feet. Without Can, that would be completely impossible. I have learned to play all the other instruments. For the first time I could play, you know, whatever. I could go back after more than twenty years to my guitar.

Working with other people – with Jah Wobble for example, or with David Sylvian – all this Can experience went into this collaboration with these people. For David Sylvian, it was completely new to have that style of working.

This open-minded conception which Can established, I think, is a good way to master the future. I can see that now, working with the young people from the electronic scene. They understand me perfectly. They are able to interact right away. This music now, with all these devices, is perfectly designed for the electronic world, it looks like. This is very living electronic music. Nothing is bad about that.