In a world drowning in celebrity, the news of Sam Shepard’s death from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a shock of the old kind: A powerful and elusive presence has vanished. It’s the type of disappearance Shepard captured with élan not just in his plays, but also with his striking, affectless acting and even in the way he carried himself through and along the edges of a culture increasingly dedicated to fame as a weapon and commodity.

It’s true that Shepard was showered with the type of accolades people pay attention to — a Pulitzer Prize, in 1979, for his play Buried Child, an Oscar nomination for Phillip Kaufman’s epic history movie The Right Stuff (1983), and a long relationship with a real Hollywood star, Jessica Lange. Yet these noteworthy accomplishments barely capture the force of his art and influence, especially in the Bay Area of the late 1970s and early ’80s.

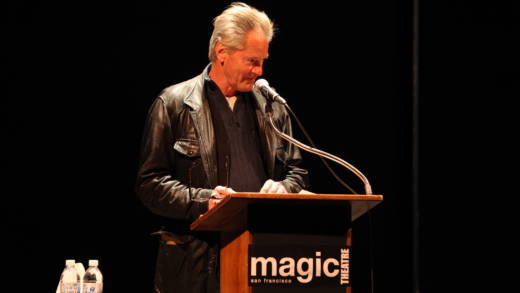

By the time Shepard became the playwright-in-residence at the Magic Theatre in 1975, he had written almost 30 plays. Without directly chronicling the Summer of Love generation, say in the way Hair (1967), Godspell (1970), and Jesus Christ Superstar (1970) would attempt, Shepard’s early work captures the dislocation, societal upheaval, and jazzy, jagged rhythms of an America in revolt against itself.

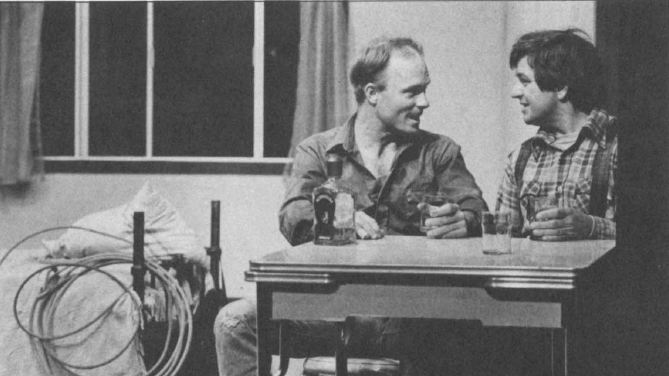

Those qualities made many of his plays such as Icarus’s Mother (1965), The Unseen Hand (1969), Cowboy Mouth (co-written with then girlfriend Patti Smith, 1971), The Tooth of the Crime (1972), and Action (1975) seem like documentaries of the Manson family’s early years. To the mainstream and even avant-garde theatrical establishment, Shepard was barely writing plays. Instead, he was creating theatrical events that more closely resembled the force of music.

The question was, where was Shepard heading? The answer was west, and to a slightly different aesthetic — one that would reimagine what realism might be after the revolution.