Yuri Herrera’s debut novel Kingdom Cons, translated this year from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman, reads as a fairy tale:

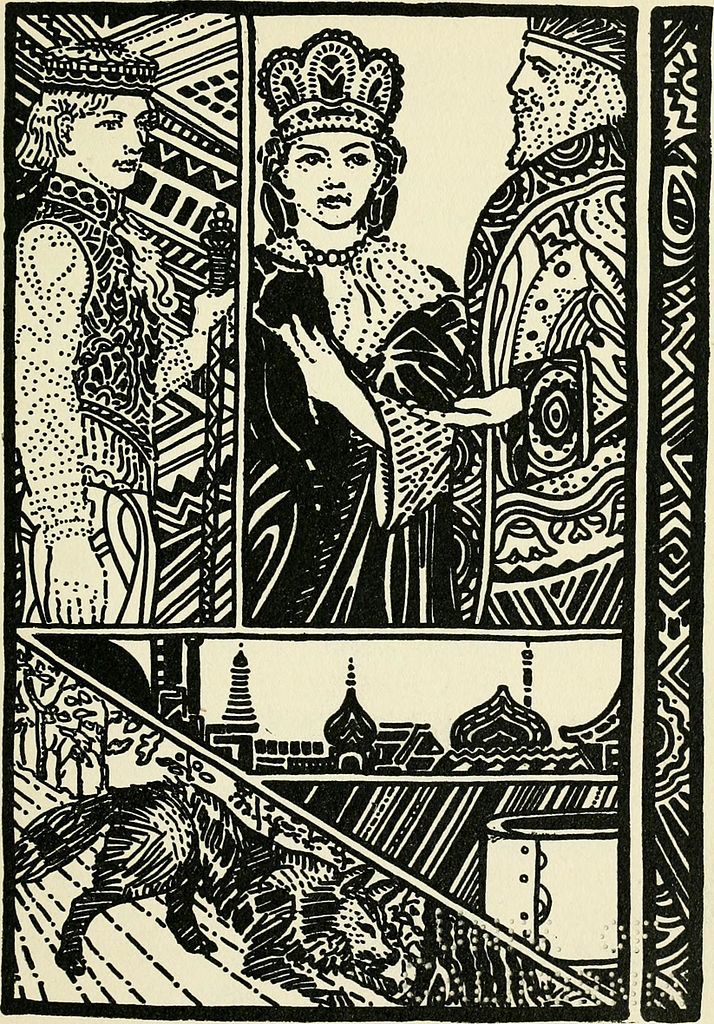

He was a King, and around him everything became meaningful. Men gave their lives for him, women gave birth for him; he protected and bestowed, and in the kingdom, through his grace, each and every subject had a precise place.

But the book just happens to be slyly dressed in fairy tale clothes. The “King” is a drug lord, his “court” a cartel, and his “kingdom” a palatial residence too pretty to be so close to Mexican-American border violence.

Colombia has put out its fair share of drug cartel novels, her authors’ imagination still reeling from the violence witnessed and experienced in the ’80s and ’90s. After the fall of Pablo Escobar, the world’s first drug lord “star,” the Colombian cartels lost their power and Mexican cartels came to the stage. Since, drug lord novels have solidified in form and tone, and they tend to have the same shape, the same clipped sentences, the same knots of intrigue.

Kingdom Cons is captivating in that Yuri Herrera has seemingly wandered off into the deserts of the genre and has come out on another shore of a different planet. While the classic story of an all-powerful drug lord warring against other cartels as well as an inside conspiracy is still present in Kingdom Cons, crime is mentioned with a side-glance, the role of power is beheld at close attention, and the language itself is short, poetic, elliptical.

In this novel, every character is referenced by their office — the Witch, the Commoner, the Journalist, the Jeweler, and of course, the Artist. Narrated by the Artist, a composer of corridos who gets taken under the wing of the King after playing boozy, heartfelt songs for him one night in a dark tavern, the story occupies itself with philosophical questions of beauty, the role of the artist in society, and the stasis of a palatial life in a kingdom where everything is preternaturally assured through violent sleights of hand happening just offstage, out there, somewhere beyond the kingdom.