Fun fact: Isadora Duncan and Jack London were contemporaries. Both were born in San Francisco, in 1877 and 1876, respectively. Both experienced poverty-stricken childhoods in Oakland and went on to make definitive marks on their art forms — London in fiction, Duncan in dance. Both lived dramatic lives full of travel, alcohol, and socialist politics.

And both died young — London in 1916 at age 40, from kidney failure; Duncan in 1927 at age 49, famously in a car accident. The long red scarf she was wearing tangled in the hubcap of a moving car. Her neck was broken.

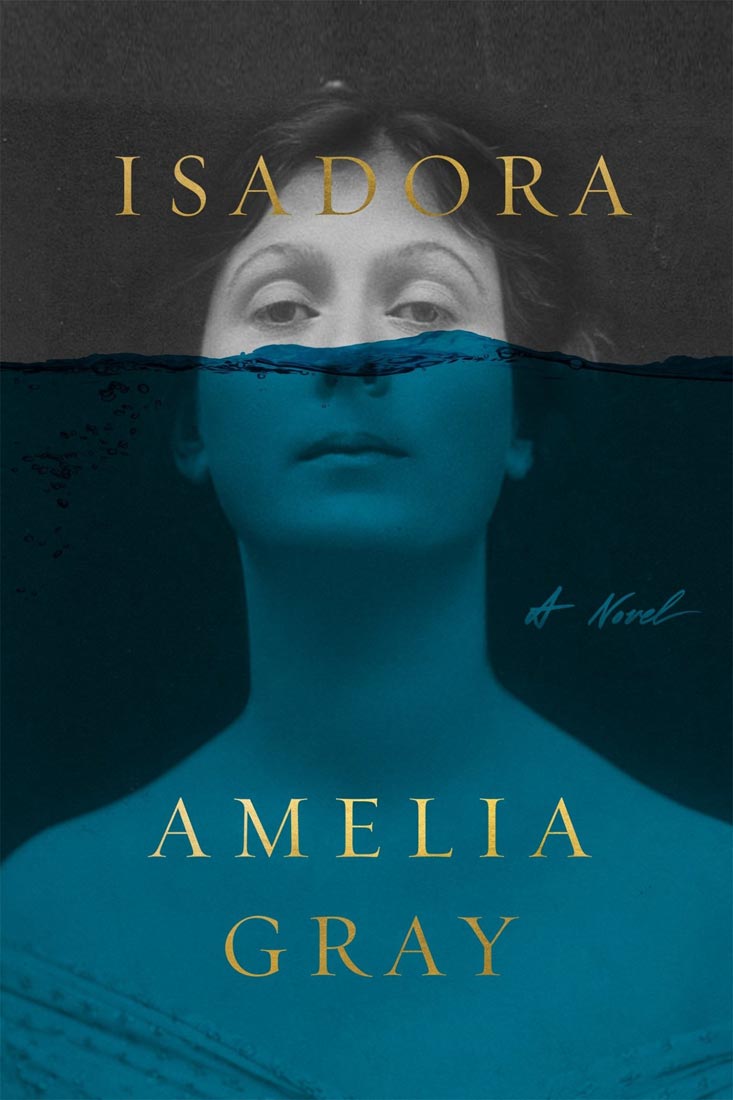

We live in a time where the lives of famous artists can attract more interest than the art itself. Sometimes this is a shame, and sometimes it’s a sign that the artist’s persona has outlived her art. Duncan’s work, while important to the history of modern dance, might look a little silly to modern eyes. Her life, however, remains fascinating, and thus, a dancer who intended to leave behind an artistic legacy is now a character in other people’s art. Last year, Lily-Rose Depp, Johnny Depp’s daughter, played Duncan in a movie called The Dancer. This month, there’s a novel, Isadora, by Amelia Gray.

Gray’s novel isn’t the stuff of a Netflix series, however. It’s a serious meditation on grief in the life of an artist. The story starts with the death of Duncan’s children, who drowned when the car they were in accidentally drove into the Seine. The novel stays so mercilessly focused on this tragic event, diving deeper into the effects of grief, that it plunges the reader into an atmosphere suffocated by the presence of loss. “A keening scream spread swiftly from my body to reach the walls and the floor,” Isadora says. “It made a residence of sound [that] echoed through my empty core, my ribs a spider’s web strung ragged across my spine, a sagging cradle for the mess of my broken heart.” She is shattered, and Gray is too ruthless a writer to look away or soften her pain.

Told in short chapters, the novel alternates four different voices: Isadora; the father of her son, Paris Singer; her sister, Elizabeth; and her lover, Max. The story moves slowly, inching through the funeral, Isadora’s travels in Europe, and her return to the dance school. There are long, lingering sections about her illness and mundane descriptions of waiting or eating or drinking. There’s an entire chapter where Paris studies the figures in the painting The Coronation of Napoleon. This focus on details dissipates the intensity of action — it’s fairly boring to read about funeral arrangements — but does humanize and intensify Duncan’s grief.