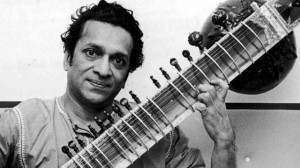

Harrison met Shankar in London in 1966 (after he’d played sitar on “Norwegian Wood”), then went to India to take sitar lessons from him. Shankar then performed with rock acts at Woodstock, Monterey and elsewhere. “I never thought,” Shankar said, “our meeting would cause such an explosion, that Indian music would suddenly appear on the pop scene.”

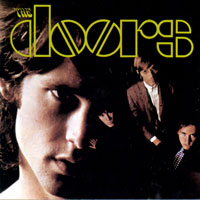

4) Through the music of Robbie Krieger and The Doors: In the late 1960s, Jim Morrison’s group also incorporated Indian music into their work, a link that’s due mainly to guitarist Robbie Krieger, who studied the music at Ravi Shankar’s Kinnara Music School in Los Angeles. Shankar opened the institution in 1967 to formalize the teachings he had been doing for decades. Krieger fell in love with the sarod, the fretless instrument that was popularized in America by Shankar’s close friend, Ali Akbar Khan. Krieger also studied the sitar. In The Doors’ song “The End,” Krieger’s use of Indian scales and intonations drives the psychedelic opening. The Indian-influenced chords repeat throughout the song, and also take up extended time elsewhere in The Doors’ most mystical tune. With Shankar’s indirect influence, “The End” becomes a moody masterpiece that brings out Jim Morrison’s chilling ruminations.

4) Through the music of Robbie Krieger and The Doors: In the late 1960s, Jim Morrison’s group also incorporated Indian music into their work, a link that’s due mainly to guitarist Robbie Krieger, who studied the music at Ravi Shankar’s Kinnara Music School in Los Angeles. Shankar opened the institution in 1967 to formalize the teachings he had been doing for decades. Krieger fell in love with the sarod, the fretless instrument that was popularized in America by Shankar’s close friend, Ali Akbar Khan. Krieger also studied the sitar. In The Doors’ song “The End,” Krieger’s use of Indian scales and intonations drives the psychedelic opening. The Indian-influenced chords repeat throughout the song, and also take up extended time elsewhere in The Doors’ most mystical tune. With Shankar’s indirect influence, “The End” becomes a moody masterpiece that brings out Jim Morrison’s chilling ruminations.

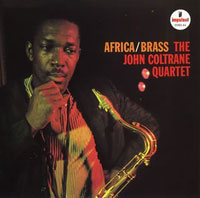

3) Through the music of John Coltrane: From the moment he first heard Ravi Shankar’s albums, jazz saxophonist John Coltrane was enthralled. In 1961, Coltrane performed at New York’s Village Vanguard with a musician backing him on tamboura, the stately Indian instrument that provides a beautiful drone sound. On his 1961 album Africa/Brass, Coltrane employed two bassists to mirror the sound of the Indian tabla drum. One of the album’s songs, “India,” was apparently based on an Indian chant whose text dates back to ancient times. Coltrane told an interviewer at that time, “I collect the records (Shankar has) made, and his music moves me. I’m certain that if I recorded with him I’d understand and appreciate his work.” Coltrane, who died in 1967, never did record with Shankar, but they met whenever possible, with Shankar giving him music lessons. In a 2002 interview I did with Shankar, he told me that he became friends with Coltrane and admired his music, but found his later, more forceful music (which some critics termed “squawking”) to be too tumultuous. Coltrane named one of his sons Ravi, and Ravi Coltrane is an active jazz musician like his father.

3) Through the music of John Coltrane: From the moment he first heard Ravi Shankar’s albums, jazz saxophonist John Coltrane was enthralled. In 1961, Coltrane performed at New York’s Village Vanguard with a musician backing him on tamboura, the stately Indian instrument that provides a beautiful drone sound. On his 1961 album Africa/Brass, Coltrane employed two bassists to mirror the sound of the Indian tabla drum. One of the album’s songs, “India,” was apparently based on an Indian chant whose text dates back to ancient times. Coltrane told an interviewer at that time, “I collect the records (Shankar has) made, and his music moves me. I’m certain that if I recorded with him I’d understand and appreciate his work.” Coltrane, who died in 1967, never did record with Shankar, but they met whenever possible, with Shankar giving him music lessons. In a 2002 interview I did with Shankar, he told me that he became friends with Coltrane and admired his music, but found his later, more forceful music (which some critics termed “squawking”) to be too tumultuous. Coltrane named one of his sons Ravi, and Ravi Coltrane is an active jazz musician like his father.

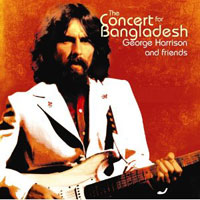

2) Through the Concert for Bangladesh: In early 1971, the burgeoning country of Bangladesh (then called East Pakistan) was experiencing the ravages of flood, food shortages and war with Pakistan. Millions of refugees were in a state of limbo in neighboring India. To raise money for relief efforts, Shankar asked Harrison for help, and Harrison responded with the Concert for Bangladesh, the first major fund-raising event of its kind. Harrison, Ringo Star, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, Billy Preston and, of course, Shankar, headlined the afternoon and evening performances at New York’s Madison Square Garden. The documentary and audio recording of the Concert for Bangladesh, which features Harrison’s song, “Bangla Desh,” (“Now please don’t turn away,” implore the lyrics, “I want to hear you say; Relieve the people of Bangladesh”) are still top-sellers. The event itself inspired the George Harrison Fund for UNICEF (an entity that continues to raise money for needy causes) and led to other musical fund-raisers (Live Aid, Live 8, etc.) that have given out tens of millions of dollars around the world.

2) Through the Concert for Bangladesh: In early 1971, the burgeoning country of Bangladesh (then called East Pakistan) was experiencing the ravages of flood, food shortages and war with Pakistan. Millions of refugees were in a state of limbo in neighboring India. To raise money for relief efforts, Shankar asked Harrison for help, and Harrison responded with the Concert for Bangladesh, the first major fund-raising event of its kind. Harrison, Ringo Star, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, Billy Preston and, of course, Shankar, headlined the afternoon and evening performances at New York’s Madison Square Garden. The documentary and audio recording of the Concert for Bangladesh, which features Harrison’s song, “Bangla Desh,” (“Now please don’t turn away,” implore the lyrics, “I want to hear you say; Relieve the people of Bangladesh”) are still top-sellers. The event itself inspired the George Harrison Fund for UNICEF (an entity that continues to raise money for needy causes) and led to other musical fund-raisers (Live Aid, Live 8, etc.) that have given out tens of millions of dollars around the world.

1) Through his offspring: Shankar is still performing at an admirable level, often with his sitar-playing daughter Anoushka, who has inherited her father’s gift for technical virtuosity. Shankar is also the father of pop singer Norah Jones, who resembles Anoushka in talent and artistic expression. Anoushka has experimented with non-traditional music, like electronica, putting the Shankar stamp on songs that are played in nightclubs instead of concert halls.

HBO’s George Harrison: Living in the Material World, which was directed by Martin Scorcese, is the latest documentary to mention Shankar’s musical influence. In 1967, it was D.A. Pennebaker who captured Shankar’s role in changing pop culture while filming the Monterey Pop Festival. Look at the film today, and you’ll see that during Shankar’s set in Monterey, white Americans greet him with a traditional namaste by pressing their hands together and directing them toward the stage. Some people in the audience (perhaps high on drugs) shake their heads and bodies like whirling dervishes, while others fall asleep, lulled by the soothing sounds of the sitar. Jimi Hendrix moves his head and body from side to side. Indian music had arrived for good. Ravi Shankar’s influence will be felt as long as his music and the music of his progeny exists on a popular level — which is to say to the end of human history.

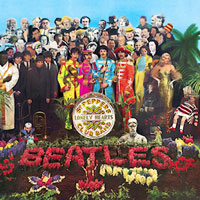

Through the music of George Harrison: Listen to The Beatles’ 1966 album Revolver, to the songs “Love You To” and “Tomorrow Never Knows,” and you hear the Shankar-influenced Harrison playing sitar, while “Within You Without You,” the dreamy 1967 soundscape that epitomizes Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, is practically a paean to Indian musical aesthetics (and the spiritual consciousness of the late ’60s). Some of Harrison’s most recognizable post-Beatles songs (“My Sweet Lord” and “Give Me Love”) echo with the spirit of Hinduism that he shared with Shankar, and Harrison produced Shankar’s 1997 album, Chants of India.

Through the music of George Harrison: Listen to The Beatles’ 1966 album Revolver, to the songs “Love You To” and “Tomorrow Never Knows,” and you hear the Shankar-influenced Harrison playing sitar, while “Within You Without You,” the dreamy 1967 soundscape that epitomizes Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, is practically a paean to Indian musical aesthetics (and the spiritual consciousness of the late ’60s). Some of Harrison’s most recognizable post-Beatles songs (“My Sweet Lord” and “Give Me Love”) echo with the spirit of Hinduism that he shared with Shankar, and Harrison produced Shankar’s 1997 album, Chants of India.