If many now feel America is entering a nightmare age, Ubuntu Theater Project’s production of Arthur Miller’s standard-bearer of thwarted American hope, Death of a Salesman, offers strange, distorted messages from the past. There’s plenty of anger in Miller’s 1949 play, but there’s no President Trump to direct it at and give it political shape.

Willy Loman, the deluded salesman of the title, is furious, and he’s furious at the system. And yet he saves his most savage attacks for his wife Linda, his sons Biff and Happy, and worst of all, himself. For Loman, the political is personal, and that’s all it is. Right from its premiere, critics have argued over the play’s curious blending of metaphysics and social protest: Is it a tragedy? Is an American tragedy even possible? And if so, has Miller achieved that exalted state?

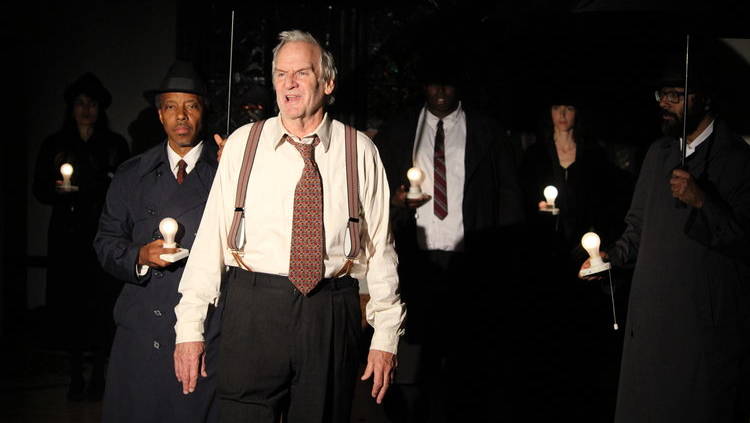

The Ubuntu production, under Michael Socrates Moran’s direction, finds its own strange path to these questions, as well as the question of what to make of Miller’s play in 2017. That it begins as a slight dream on a fall day is the first surprise. You enter the theater and the actors are already there, the stage covered with what looks like freshly blown leaves. And there’s Loman, sleeping on a mound of suitcases as the cast wanders about the stage in raincoats and fedoras.

It’s an arresting and beautiful opening image, perfectly calibrated to suit Ubuntu’s church-loft theater — a Salesman filtered through the eyes of Rene Magritte and Samuel Beckett. Long-time Bay Area actor Julian López-Morillas’ performance is superb, both in playing Loman, and, more importantly, in playing the character in a way that feels as if he’s seeped himself into the scenery. It’s a nightmare, but a gentle, surrealist one tinged with care.

And that’s the key tension in Ubuntu’s production: the weird relationship between kindness and horror. It’s not that Loman is without people who love him, or that he lives in a world without compassion. It’s that legitimate care and love make him feel worthless. Linda’s defense of his so-called importance — “attention must be paid” — leads Loman to further pain and delusions. His neighbor Charley’s offer of help, in the form of a job with enough money to survive, comes as a stinging rebuke. Sixty-eight years later, Loman’s despair probably would have led him to embrace the raucous anger of Trump or the white-hot socialism of Bernie Sanders, but here he’s just lost.