That Orner manages to swing between his Kafka theories and his own visit to Harbin Hot Springs (he never mentions it by name, but anyone who’s been to the famously naked and watery New Age destination, burned to the ground in 2015, knows what Orner is talking about) is quite brilliant. At the hot springs, where he’s gone to recover from the bewildering and exhausting ruins of a marriage, Orner escapes from the “competitively exposed flesh” to a thatched hut at the top of a mountain, “two yoga mats side by romantic side.” After an attempt to meditate, foiled by nervous agitation, Orner is approached by a bearded guy wearing “nothing but hiking boots and a loose thong.”

Instead of making fun of the young hippie, as most would be inclined to do, Orner moves into a reflection on the nature of loneliness, concluding with a reluctant gratitude to the man for breaking the silence of those Calistoga woods. Kafka has written of this need for a common humanity with the metaphor of the street window, where the lonely soul can stand and watch the tumult, wagons, and people, and be drawn into the “human harmony.”

Orner writes:

At some point, much as we talk a big game about needing to go it alone, we can’t help but be pulled to the window, to the noise and the voices. Come on into my hut and tell me about the demonology of garments, thong man, I’ll listen.

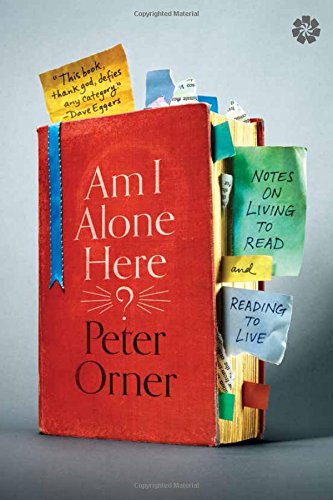

Books are the glue that holds Orner’s essays together, but this Am I Alone Here is also a memoir. At its core, this is the story of Orner’s semi-estranged relationship with his father, now deceased. Dave Eggers suggests reading the book from beginning to end, rather than dipping in to individual essays. I agree. The thread running through these essays is the unresolved story of a father and son, and how they push through this life, enmeshed in an antagonistic, distant love.

In Orner, you’ll also find a modern author willing to err on the side of loneliness. It’s okay to be the crazy guy in the dark garage, surrounded by dusty books and mice, muttering about some long-dead 19th century writer. Still, Am I Alone Here serves as a crafty play on the idea. Because, as Orner might himself admit, he’s not alone. He has books as companions. As reference points. As teachers. As instigators of a deep, gracious appreciation for the “phenomenal muddle” that is being alive. He’s also a father and a partner. So even when alone, he’s not, really.

I will say that reading this book made me feel woefully under-read. Out of dozens of books and writers mentioned in Am I Alone Here, I can attest to having read only a few, and that as the holder of an English degree from a relatively prestigious UC school. Yes, I’ve read To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf and Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston. Yes, I’ve read a Chekhov story here and there (you can’t get out alive with an English degree without reading The Lady with the Lapdog at least, oh, a dozen times), and some Kafka. Who didn’t read The Metamorphosis in high school?

I’ve also enjoyed a few stories by William Trevor, some of which have stuck with me for a long time. But with Orner, it’s not the reading so much as the long tail of processing. Orner makes me jealous with the way that he’s internalized and inhabited a Trevor story (“The Dressmaker’s Child” from at Cheating at Canasta) so completely that it invades his dreams and makes him question whether a particular event actually happened to him and not a character in the story.

With that said, one could spend the next 10 years catching up on the reading list compiled strictly from Orner’s book: Breece D’J Pancake, Frank O’ Connor, Eudora Welty, Robert Walser, Juan Rulfo, William Maxwell, Angela Carter, Bernard Malamud, Gina Berriault, Andre Dubus, Isaac Babel, Wright Morris, Victor Martinez, Mavis Gallant, Saul Bellow, Heinrich Boll, James Salter, Yasunari Kawabata, Elias Canetti, and more.

Not that this would be a chore. Honestly, Am I Alone Here made me want to close myself in a dusty bookstore for a few months to read until my eyes burn and my soul is washed clean of the trivial. Alone there, yes. But with all the world before me.