When I was a fresh-faced MFA student at a San Francisco private college, we were regularly encouraged by our renegade teachers to break form, and approach our writing with openness to experimentation. I tried — and failed — to do so in my short stories, over and over. You’d think it would be easy to break the rules. It’s not.

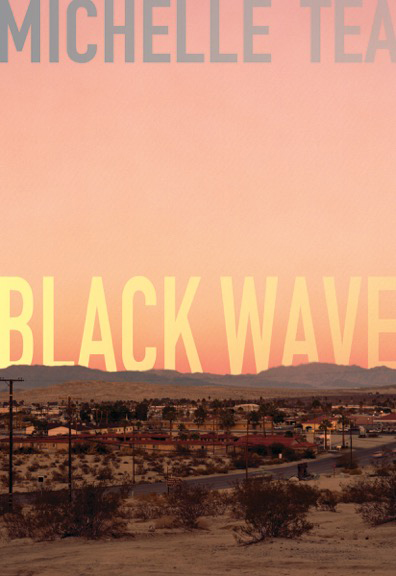

So I admire Michelle Tea’s successful attempt to bring transparency to the “strange obligations of storytelling” in her latest book, the hybrid fiction-memoir Black Wave (The Feminist Press; 2016). Last year, I interviewed Tea on the release of her 2015 memoir How to Grow Up, and at the time, she mentioned Black Wave, explaining that she’d been working on a new memoir but had gotten waylaid midway through the process. Her ex had asked that Tea not write about their relationship, but the book’s entire narrative timeline hinged upon it. Tellingly, especially in light of the destabilized, failing world captured in Black Wave, Tea also said of San Francisco: “The landscape I inhabited [in the 1990’s] is just gone.”

Rather than abandoning the manuscript, Tea dug in, throwing out normative narrative expectations with the dirty bathwater. Call it the ultimate queer narrative. It works.

Black Wave opens on Valencia Street at the Albion, a dive bar in the Mission District. If you’ve read Tea’s previous books — The Passionate Mistakes and Intricate Corruption of One Girl in America, Valencia, The Chelsea Whistle, Rent Girl — then you’re familiar with her tales of wild, creative, sex-fueled, drug and alcohol-drenched lifestyles in San Francisco’s queer artistic haven of the nineties. And yes, the first half of Black Wave dwells in this same landscape, but with a twist. It’s 1999, the first tech bubble has raised rents beyond reason, yuppies are taking over the Mission, and the world is, literally, about to end. The native plants have died; the only vegetation thriving are invasive weeds like kudzo. The trees have crumbled to dust. The ocean is blanketed in a thick, poisonous fog from toxins and underwater nuclear tests. Still, everyone goes about their business, only with more sun protection, like frogs in proverbial water slowly coming to a boil. “The ocean was a giant toilet lapping at San Francisco’s edges,” Tea writes, “but mainly things were functioning.”