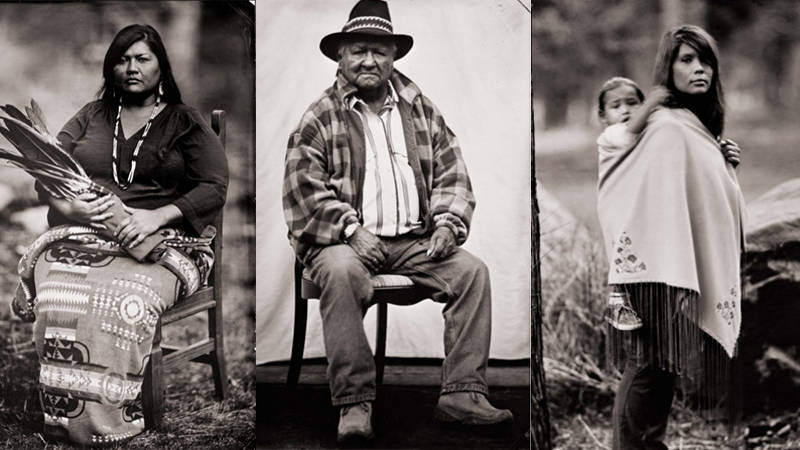

On July 21, Spayne Martinez walked into the California Historical Society at the corner of Annie and Mission Streets in San Francisco. As an Academy of Art University alumna, she probably walked past the building countless times on her way to class in SOMA, but never with a 12-foot picture of her on display in the front windows. Inside, Martinez enthusiastically greeted Ed Drew, the photographer of behind Native Portraits: Contemporary Tintypes, on view at the CHS through Nov. 27.

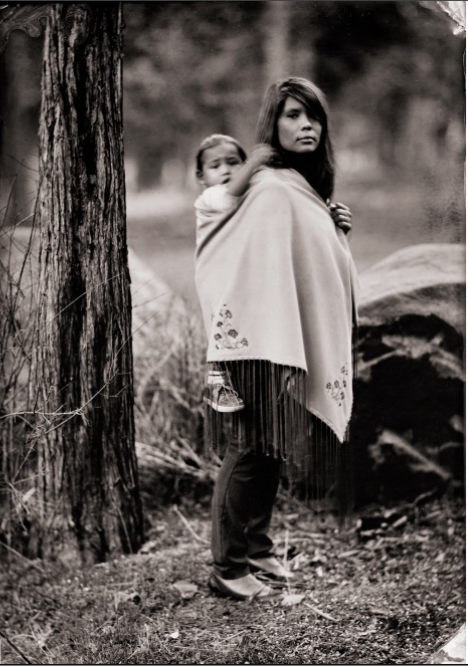

Martinez beamed as she pointed out her son strapped to her back in the portrait and her cousin’s portrait a few frames down. As a professional portrait photographer herself and a tribal community member of the Klamath Basin, Martinez has a unique insight into the photographic representations of Native people.

In a recent Instagram post, Spayne holds a book of Edward S. Curtis photographs over her face with the caption “Oh Edward” (cue exasperated sigh). Curtis is best known for documenting “The North American Indian” in the early 1900s. Many Native Americans and Canada’s First People criticize Curtis for fabricating historically inaccurate representations of Native people, erasing their modern identities.